The Republic of Texas existed as an independent nation for a decade (1836-1845), wedged politically and geographically between the United States and Mexico. Though short-lived, the republic’s existence helped shape not only Texas identity but also U.S.-Mexico relations and internal politics within both countries. From its declaration of independence to its annexation into the United States, the story of the Lone Star Republic is one of aspiration, instability, and shifting identities.

Revolution and Political Identity

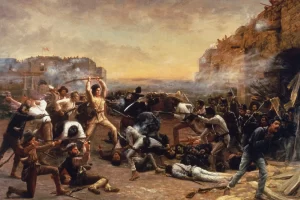

The Texas Revolution, launched in late 1835, was fueled by rising tensions between Anglo-American settlers in Mexican Texas and the centralist policies of President Antonio López de Santa Anna. After a series of clashes—including the famous siege at the Alamo and the massacre at Goliad—Texian forces won a decisive victory at the Battle of San Jacinto in April 1836. There, General Sam Houston’s troops captured Santa Anna and forced him to sign documents recognizing Texas independence, though the Mexican government never formally acknowledged the loss.

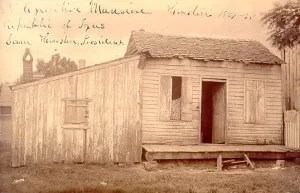

In March 1836, Texian delegates convened at Washington-on-the-Brazos to draft and sign the Declaration of Independence, asserting that Mexico had violated their rights under the federalist Constitution of 1824. A provisional government was formed, and soon after, the constitution of the Republic of Texas (1836) was adopted, blending elements of the U.S. Constitution with unique provisions reflective of the frontier context and the revolutionary moment.

Although Texan revolutionaries declared the existence of an independent republic, many of them envisioned that the republic eventually would be absorbed by the U.S. American immigration to Texas had begun just 12 years before the revolt, which meant that all adult Texans were American-born. Naturally, therefore, Texans — or ‘Texians’ as they were called at that time — had a desire for union with their native land.

Advertisement

During the Texas Revolution, Texians consciously copied the political language and ideas of the American Revolution, which had secured U.S. independence from the United Kingdom. They viewed their victory against Santa Anna largely as a continuation of the American Revolution — a triumph of the same spirit — not as a break from the American Revolution and the political system it had spawned. The structure and laws of the new republic mimicked the U.S. system in many ways.

“The Republic of Texas was supposed to be ephemeral. The people of Texas voted overwhelming approval of union with the United States on the same ballot by which they elected the Republic’s officers.”1

T.R. Fehrenbach, ‘Lone Star: A History of Texas and the Texans,’ 1968

T.R. Fehrenbach, author of a best-selling 1968 history of Texas, wrote, “The [Anglo-American] people of Texas had cultural, economic, political, and military reasons for seeking annexation, and obviously the United States had a tremendous strategic stake in Texas. Texas blocked American expansion to the Pacific, and a weak, unstable nation American borders invited penetration by still-ambitious European powers.” However, the U.S. refused to annex Texas for nearly a decade, due to internal political divides. Opponents of annexation cited the risk of war with Mexico, and the fact that annexation would strengthen the pro-slavery faction within the U.S. Congress.

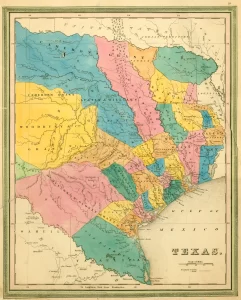

As prospects for annexation remained uncertain, a unique brand of Texan nationalism developed, alongside a pan-Southern cultural identity promoted by the planter elite, but not shared by all Texans. In particular, the second president of Texas, Mirabeau Lamar, embraced a vision of Texas as a continental power with western territories stretching into New Mexico and beyond.

In the meantime, a substantial minority of Texas residents still viewed themselves as citizens of Mexico. The native-born Tejano population was Spanish-speaking, unlike the immigrant ‘Anglos,’ and they were not accustomed to the American-style laws and political institutions of the republic. Tejanos increasingly found themselves politically and economically marginalized, even though a handful of Tejano leaders had played a major role in the Texas Revolution. This led to violence in some areas, such as the Córdova Rebellion in Nacogdoches and the Cortina Wars in the Rio Grande Valley. The arrival of European settlers, in particular Germans, further complicated the situation, as each group brought its own religious, ethnic, and political traditions.

These competing and overlapping political identities — Texan, Southern, Mexican, European, and American — remained in flux throughout the Republic Era. Most Texans supported annexation in 1846, when the republic ceased to exist, but each of these identities would endure.

The Contrasting Presidencies of Houston and Lamar

From the beginning, the fledgling republic faced political, military, and economic uncertainty. The interim government struggled to establish order, issue currency, and protect the population amid threats of renewed Mexican invasion. In October 1836, Sam Houston was elected the first official president of the Republic of Texas. When he took office, Texas was alive with revolutionary fervor and the thrill of independence, but it was diplomatically isolated, lacked reliable sources of government revenue, and possessed only rudimentary laws and institutions.

Houston prioritized peace with Native American tribes and fiscal restraint. His administration negotiated several treaties with tribes such as the Cherokee, though these agreements were often undermined by settler encroachment and shifting political leadership.

The fiscal situation worsened throughout Houston’s term — in part because of the republic’s weak institutions, in part because of a sharp drop in cotton prices and a continental banking crisis known as the Panic of 1837. Historian Fehrenbach wrote, “Despite Houston’s innate conservatism, the government went further and further in debt. Houston was forced to spend some $2,000,000, and revenues in no way matched this. Texas’s only productive tax was a tariff, ranging from 1 percent on bread and flour to 50 percent on luxuries like silk. Such levies as tonnage fees, the poll tax, business taxes, and license or land fees raised only small amounts; the direct property tax was virtually uncollectable. Texans did not like taxes.”2

“The only substantial money that arrived was a loan of $457,380 from the Bank of the United States in Pennsylvania… In the end, Houston did what every government in such a situation did, although everyone knew the solution’s inherent folly. The Government of Texas in 1837 started printing paper money, in the form of promissory notes. At first, these notes held their value very well, but with the second issue, in 1838, they depreciated to about seventy cents on the dollar.”

Advertisement

In the meantime, Houston’s political opponents, including Vice President Mirabeau B. Lamar, pushed for a more aggressive expansionist posture. When Lamar succeeded Houston in 1838, his administration reversed many of Houston’s policies—relocating the capital to Austin, attempting to conquer parts of New Mexico, and launching military campaigns against the Comanche. The financial cost of these efforts further strained the republic’s limited resources and deepened domestic divisions.

“Texas is overwhelmed with army and navy officers—there are enough for Russia—and poor Texas is without the means to support them many weeks longer,” wrote Anson Jones, a senior statesman of the republic, in his diary in August 1840, during the second year of Lamar’s presidency.3 He added the next day, “Borrowing may serve to protract the crisis awhile, but come it must with a tremendous crash, ere long.”4

Jones, a physician who held several high offices in the republican government, ultimately becoming its last president, criticized Lamar’s Indian policy and aggression toward Mexico. He wrote,

“President Lamar may mean well—I am not disposed to impugn his motives—he has fine belles-lettres talents, and is an elegant writer. But his mind is altogether of a dreamy, poetic order, a sort of political Troubadour and Crusader, and wholly unfit by habit or education for the active duties, and the every-day realities of his present station. Texas is too small for a man of such wild, visionary, ‘vaulting ambition.'”5

When Sam Houston returned to the presidency in 1841, he quickly moved to reverse many of Lamar’s initiatives. He renewed efforts to make peace with Indian tribes, scaled back military operations, and imposed fiscal restraint to address the republic’s mounting debt. Despite these measures, Texas remained heavily indebted by the time Anson Jones assumed the presidency in 1844—fulfilling the concerns he had voiced years earlier in his diary.

Diplomatic Relations

From its inception, the Republic of Texas pursued diplomatic recognition as a means of securing survival and asserting legitimacy on the international stage. The new government viewed foreign acknowledgment as critical to deterring a Mexican reconquest and boosting internal confidence. The United States formally recognized Texas in March 1837, but immediate annexation was deferred due to domestic political concerns—chiefly the expansion of slavery, sectional balance between free and slave states, and the risk of war with Mexico.

While Texas maintained close cultural and economic ties with the U.S., its leadership also sought recognition from European powers to diversify its options and gain leverage in negotiations. France extended diplomatic recognition in 1839, and Great Britain followed in 1840, establishing legations in the republic’s temporary capital of Houston. British policymakers saw an independent Texas as a potential buffer state that could limit the territorial ambitions of the United States and open new markets for British industry.

Texas also courted smaller powers, including the Netherlands and Belgium, both of which expressed interest in trade and investment. A treaty of amity and commerce was signed with Belgium in 1841, and Dutch merchants explored commercial routes to Galveston.

Despite these successes, the republic remained diplomatically precarious. None of the treaties provided military guarantees, and Mexico continued to reject Texas independence, launching periodic raids and issuing diplomatic protests.

By the early 1840s, Britain and France stepped up their involvement—not to support annexation, but to prevent it. The British government, fearing U.S. expansion, offered to broker peace between Texas and Mexico in exchange for Mexican recognition of Texas as an independent state. President Anson Jones briefly entertained this proposal, hoping it might offer a peaceful resolution and preserve Texan sovereignty.

Slavery & the Social Order

The Constitution of the Republic of Texas enshrined the legality of slavery, explicitly prohibiting emancipation and banning free Black people from residing in the country without legislative approval. This legal framework reflected both the backgrounds of many Anglo-American settlers and the economic aspirations of a plantation elite. By the early 1840s, the enslaved population was growing, especially in the fertile lands of East Texas.

At the same time, Tejanos—Mexican Texans who had supported the revolution—found themselves politically marginalized in the new republic. Some remained local leaders, but many lost influence amid rising Anglo dominance and a political climate that increasingly associated Mexican identity with foreign threat.

Native Americans faced some of the harshest consequences of independence. Comanche, Kiowa, and Apache groups resisted Anglo expansion, leading to cycles of violence and dispossession. President Lamar’s campaigns against Native tribes, in particular, led to mass killings, forced migrations, and a militarized frontier.

Political Instability & Governance

The republic was governed by a president, a bicameral Congress, and a judiciary modeled after the U.S. system. Presidential elections occurred every three years, with presidents barred from serving consecutive terms. Sam Houston served two non-consecutive terms, with Mirabeau Lamar and Anson Jones also holding the office.

Despite formal structures, political stability was elusive. The government issued paper currency, known as “redbacks,” which rapidly lost value due to inflation and lack of backing. Military expeditions, like the ill-fated Santa Fe Expedition and the Mier Expedition, depleted funds and weakened morale. Civilian control over the military was frequently tested, and frontier justice often prevailed over formal legal systems in rural areas.

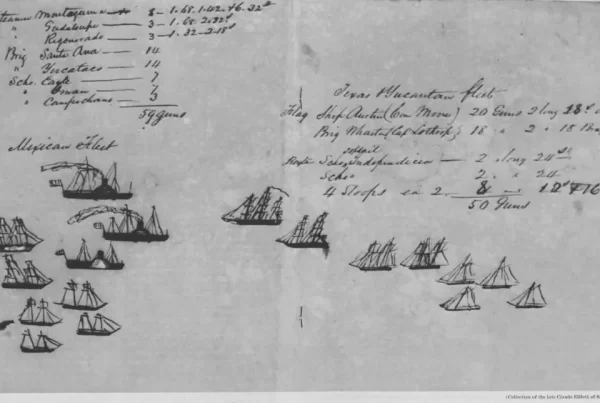

Tensions between political leaders and military officers occasionally flared, with some commanders acting independently or disregarding presidential directives. For example, Commodore Edwin W. Moore of the Texas Navy refused to follow President Sam Houston’s order to return to port and instead sailed to the Yucatán coast to assist Mexican federalists. Houston, frustrated by what he viewed as insubordination, declared Moore a pirate and revoked his commission—though the Texas Congress later reinstated him.

Debt remained a chronic problem. Multiple loan negotiations with European banks failed due to instability, forcing the republic to rely more heavily on land speculation and customs revenue. By the time Texas joined the United States in 1845, its public debt exceeded $10 million—a staggering sum relative to its population and revenue capacity. Efforts to raise funds through land grants and customs duties met only partial success.

Military Forces of the Republic

Although the Republic of Texas authorized the creation of a regular army, it struggled to retain and pay its soldiers, secure armaments and supplies, and professionalize the force. While the memory of volunteer fighters at San Jacinto and the Alamo became central to the republic’s identity, the reality of military preparedness was shaped by financial hardship, political division, and amateur leadership.

This resulted in low morale and indiscipline: “A state of war against Mexico still existed so that maintenance of an army was imperative, but the Republic had no money with which to pay its soldiers, and the morale and the caliber of these men were deteriorating. Hordes of adventurers had come from the United States after the Battle of San Jacinto to seek their fortunes as soldiers on the frontier… But after several months of no pay and no action, the army began to seek excitement and booty on its own initiative.”6

Advertisement

Thomas J. Rusk, a capable veteran of the Texas Revolution, served as Secretary of War, but the commander-in-chief of the army during the first years of the republic, Felix Huston, had no military experience. He was charismatic, popular with the troops, and eager for military glory, advocating for an invasion of Matamoros.7 But he was ineffective and prideful, even challenging his own deputy, Albert Sidney Johnston, to a duel, wounding him in the hip.

Johnson, who went on to become a renowned general in the Confederate Army, later stated that he fought his commanding officer “as a public duty.” Though he had little respect for the practice of dueling, he viewed Huston as a threat to the safety of the republic, stating, “General Huston embodied the lawless spirit in the army, which had to be met and controlled at whatever personal peril.”8

President Sam Houston, aware of the unruly state of the army, preferred to rely on diplomacy and ad hoc defense. He allowed the army to wither during his first term. Houston’s successor, Mirabeau B. Lamar, reversed course—expanding military expenditures and launching offensives against Native American tribes and distant Mexican territory. These ventures, including the costly and unsuccessful Santa Fe Expedition, drained the treasury and highlighted the limits of Texas’s military reach.

Meanwhile, the Texas Navy, created to disrupt Mexican shipping and bolster diplomatic recognition, saw intermittent success under commanders like Edwin Moore but was ultimately disbanded amid political controversy and budgetary pressure.

More enduring than the army and navy were the local militias and the Texas Rangers. Organized by region and often operating with limited oversight, militias served as the republic’s main instrument of frontier defense and internal security. They responded to Native raids, enforced order in remote settlements, and supported national mobilization when needed. The Rangers, a loosely structured paramilitary force, gained prominence during this period for their role in scouting, patrolling, and conducting reprisals—especially during Lamar’s campaigns. Though ill-equipped and decentralized, these volunteer forces were well adapted to the challenges of the borderlands and laid the groundwork for the military traditions Texas would carry into statehood.

Movement Toward Annexation

Though annexation to the United States had always been popular among many Texans, it remained diplomatically delicate. Slavery was the central obstacle. Northern U.S. politicians feared that admitting Texas would tip the balance toward the slaveholding South. Others worried it would provoke war with Mexico, which still claimed Texas as its own.

Over time, however, U.S. attitudes began to shift. The presidency of James K. Polk, an ardent expansionist, accelerated annexation plans. Fears of British influence in Texas and a growing sense of Manifest Destiny helped overcome domestic hesitation.

In 1845, the U.S. Congress passed a joint resolution offering to admit Texas as a state. Texans voted overwhelmingly in favor of annexation in a public referendum. On December 29, 1845, Texas was formally admitted to the Union, ending its status as an independent republic.

Legacy of the Republic

The Republic of Texas occupies a unique place in American history as the only U.S. state to have existed as an independent, internationally recognized republic before joining the Union. Its existence raises enduring questions about sovereignty, identity, and the messy intersections of race, economics, and diplomacy.

The republic’s institutions—its Constitution, land system, and political culture—left lasting marks on the structure of Texas government, many of which persist today. The state’s preference for decentralized power, its independent streak in policymaking, and its complex relationship with federal authority all trace back to the era of the republic.

At the same time, the republic’s legacy is entangled with injustice. Its reliance on slavery, its violent displacement of Native peoples, and its marginalization of Tejanos are part of the historical fabric. These tensions remain relevant to discussions of civil rights in Texas, cultural identity, and historical memory.

Sources Cited

- T. R. Fehrenbach, Lone Star: A History of Texas and the Texans (1968; reprint, New York: Open Road Media, 2014), 70. ↩︎

- Fehrenbach, Lone Star, 132. ↩︎

- Anson Jones, Memoranda and Official Correspondence Relating to the Republic of Texas, Its History and Annexation: Including a Brief Autobiography of the Author (New York: D. Appleton & Company, 1859), 34, diary entry, August 15, 1840. ↩︎

- Jones, Memoranda and Official Correspondence, 34, diary entry, August 16, 1840. ↩︎

- Jones, Memoranda and Official Correspondence, 34, diary entry, August 20, 1840. ↩︎

- Patsy McDonald Spaw, ed., The Texas Senate Volume I: Republic to Civil War, 1836–1861 (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 1990), 20. ↩︎

- Huston had raised a company of volunteers in Mississippi and Kentucky to aid the Texas Revolution, but they arrived too late to participate in the fighting. According to a biography published by the Texas State Historical Association, “Under Huston the camps of the army became the resting place for idlers and brawlers.” ↩︎

- William Preston Johnston, The Life of General Albert Sidney Johnston: Embracing His Services in the Armies of the United States, the Republic of Texas, and the Confederate States (New York: Appleton and Company, 1878), 80. ↩︎

📚 Curated Texas History Books

Dive deeper into this topic with these handpicked titles:

- The Raven: A Biography of Sam Houston

- Lone Star Nation: The Epic Story of the Battle for Texas Independence

- Wars of the Mexican Gulf: The Breakaway Republics of Texas and Yucatan, US-Mexican War, and Limits of Empire 1835-1850

- Women and the Texas Revolution

- Texian Iliad: A Military History of the Texas Revolution, 1835-1836

Texapedia earns a commission from qualifying purchases. Earnings are used to support the ongoing work of maintaining and growing this encyclopedia.