The Texas Revolution marked the violent collapse of Mexican control over Texas and the founding of a breakaway republic. Though brief, the Texas Revolution was linked to a broader political crisis within Mexico, marked by regional uprisings against the centralist regime of President Antonio López de Santa Anna. After a series of military engagements from the fall of 1835 to the spring of 1836, Texian forces captured Santa Anna and forced his army to retreat, securing Texan independence.

The revolution involved a range of actors with distinct agendas. On one side stood the Mexican Army, commanded by Santa Anna, who sought to reassert national control over Texas and intimidate other rebellious Mexican states by crushing the Texan revolt. Opposing him were both Tejano federalists, who initially hoped to restore the Constitution of 1824, and Anglo settlers (called Texians) who favored either continued autonomy within Mexico or outright independence.

Prelude to Rebellion

For a decade, Texas had been joined with Coahuila as a single state under the federalist (decentralized) Mexican Constitution of 1824. Both Anglos and Tejanos within Texas largely governed themselves; the state government in distant Saltillo and the federal government in Mexico City exercised little direct control over their affairs.

At a convention in 1833, the Texians drafted their own state constitution and asked for the separation of Texas from Coahuila. If the Mexican authorities had engaged with this request, the revolution might never have happened. The convention appointed the bilingual founder of the largest Anglo colony, “Don Estevan” (Stephen F. Austin), along with Juan Erasmo Seguín and Dr. James B. Miller, to carry the petition to Mexico City.

Austin was optimistic that Texas would flourish as a state within the Mexican republic. But he also foresaw trouble if Mexican national authorities refused the demand. On the eve of his departure to Mexico City, he wrote,

“We have just had a convention and unanimously decided to apply for a State [Government] and I was appointed by the convention to take in the application. Should it be refused, I think it will be the greatest error that the Mexican Government have ever committed. Texas is now able to sustain a State Government and cannot do any longer without one, and a refusal will inevitably produce a violent agitation here of some kind and an unprofitable and troublesome one for Mexico…. We shall have a regular and good government and this country [Texas] as a state of Mexico will flourish rapidly, and be one of the most valuable members of the confederacy. We have no government now that deserves the name of one, and a refusal to give us one will be bad policy, very bad indeed.”1

Mexico’s national government, then in upheaval as Santa Anna ascended to power, did not entertain the petition. Instead, it imprisoned Austin in Mexico City and dispatched troops to Texas to quell unrest and intimidate dissidents. In the meantime, Santa Anna and his allies in the Mexican Congress moved to tighten national control over the federal Mexican states, which hitherto had exercised considerable autonomy under the 1824 constitution.

These measures emboldened the radicals among the Texians, who believed the time for politics had ended and the time for fighting had arrived. However, the settlers were divided over the question of independence. Many newly arrived immigrants from the United States preferred to break away from Mexico and become an independent republic, before eventually joining the United States. Others, including many of the more established settler families, preferred to ally themselves with federalist insurgents who were rising up in other Mexican states.

Ultimately, the separatists and American nationalists emerged as the dominant party within the revolutionary camp. Among the leaders of this group was Sam Houston, a former congressman and governor of Tennessee, and a political protégé of U.S. President Andrew Jackson. He openly envisioned eventual annexation, and served as both commander of the Texian Army and the first president of the Republic of Texas.

In addition to the constitutional crisis in Mexico, historians have offered several other explanations for the revolt, including land speculation, cultural prejudice against Mexicans, and the American practice of slavery—which was officially prohibited in Mexico but tolerated in Texas among American settlers. While the revolutionaries had varied motives and ideologies, the immediate spark for the conflict was the abrogation of the Mexican Constitution of 1824 and Santa Anna’s consolidation of power through military means. His dismantling of the federalist system—combined with the deployment of troops to Texas—transformed local grievances into open rebellion.

First Hostilities

The first shots of the Texas Revolution were fired on October 2, 1835, near the Guadalupe River at Gonzales. Mexican troops under Colonel Domingo de Ugartechea had been sent to retrieve a small cannon previously lent to settlers for defense against Native raids. Amid growing unrest across Texas, Ugartechea feared the cannon might be turned against centralist forces and sought to reassert authority before open rebellion spread.

The local alcalde, Andrew Ponton, refused to surrender the cannon without written orders, and settlers quickly organized a militia. As reinforcements arrived from surrounding communities, the Texians took the initiative. In the early morning hours, they crossed the river and attacked the Mexican encampment, raising a homemade banner with the words “Come and Take It.” After a short skirmish, the Mexican troops withdrew, leaving the cannon behind. There were no casualties on the Texan side, and two dead on the Mexican side.

Noah Smithwick, an early settler in Texas who was with the Texian insurgents at Gonzales, later recalled in his memoirs that the cannon had been “useless,” except that it could make a loud noise: “Its principal merit as a weapon of defense lay in its presence and the noise it could make, the Indians being very much afraid of cannon. But it was the match that fired the mine, already primed and loaded… It was our Lexington.”2

Thus the war for Texas Independence began with a fight for a “useless” cannon. About 150 armed Texan militia were on hand for the “battle” of Gonzales, including small companies from settlements along the Brazos, Colorado, and LaGrange. This force demonstrated many of the qualities that would come to define the revolutionary army throughout the war: aggressive, voluntary, self-armed, and with decentralized leadership. Smithwick said, “I cannot remember that there was any distinct understanding as to the position we were to assume toward Mexico. Some were for independence; some for the constitution of 1824; and some for anything, just so it was a row. But we were all ready to fight.”3

Though the skirmish was brief and casualties were minimal, it marked a point of no return. Texans had defied federal orders with armed force. The confrontation at Gonzales followed months of rising tension between colonists and Mexican authorities, especially after General Martín Perfecto de Cos announced plans to reoccupy Texas and prosecute perceived dissidents. Settlers feared a permanent military occupation and the loss of their local institutions. Many still identified as loyal Mexican citizens, but believed Santa Anna’s government had overstepped its constitutional limits.

In the weeks after Gonzales, Texian volunteers began organizing under local committees of safety. Some sought to defend their rights under the Constitution of 1824. Others already called for separation. Sam Houston, newly arrived in Texas and appointed to lead a proposed “regular army,” issued a recruitment proclamation in December 1835—but most military activity remained in the hands of citizen militias and spontaneous volunteer units.

While General Cós fortified his position in San Antonio de Béxar, Texian forces moved to cut off supplies and reinforcements. On October 9, 1835, volunteers led by George Collingsworth captured the presidio at Goliad without serious resistance, seizing munitions.

The fall of Goliad alarmed Mexican authorities, as it disrupted a key supply corridor from the Gulf Coast to the interior. With both Goliad and Gonzales in Texian hands, the rebellion no longer appeared to be a local flare-up—it was a coordinated uprising with the potential to isolate and encircle Cós’s garrison in San Antonio.

In Mexico City, President Santa Anna saw the developments as a challenge to national authority and began preparing a larger military expedition to suppress the revolt. At the same time, his government escalated its crackdown on dissent, silencing federalist sympathizers across Mexico.

The Capture of San Antonio

For the Texians, the capture of Goliad boosted morale and emboldened the rebellion. Their attention now turned inland toward San Antonio de Béxar, the regional seat of Mexican power. There, General Martín Perfecto de Cos remained entrenched with several hundred Mexican troops.

Roughly 300 Texian volunteers, under the provisional leadership of Stephen F. Austin and later Edward Burleson, laid siege to the city throughout the fall. Skirmishes flared intermittently, including the Battle of Concepción on October 28, in which a smaller Texian force led by James Bowie and James Fannin repelled a much larger Mexican column. The engagement raised rebel confidence, but logistical constraints and command disagreements delayed a full assault for several weeks.

The turning point came in early December. Frustrated by inaction, veteran soldier Ben Milam rallied volunteers to launch an attack. Beginning December 5, Texians and allied Tejano fighters—including a company under Juan Seguín—fought their way through the city in bitter street-to-street combat. Milam was killed on the third day, but the assault continued under Frank Johnson.

On December 9, Cos surrendered. In exchange for clemency, he and his remaining soldiers agreed to retreat beyond the Rio Grande and not take up arms again against the Constitution of 1824. The Texians, for the moment, controlled the region.

The capture of San Antonio gave many the impression that the conflict had ended. With Mexican forces in retreat, some volunteers returned home. Others saw it as proof that military occupation had been repelled and that the constitutional order could be restored. But the revolution had already begun to move beyond those goals. Even as some settlers still professed loyalty to the Mexican federation, others were preparing for a clean break.

During the Texas Revolution and the early years of the Republic, Anglo-American settlers were commonly referred to as Texians. By the late 19th century, Texan had largely replaced Texian in common usage. Today, Texian is primarily used in historical contexts.

Declaration of Independence

In the wake of the Texian victory at San Antonio, political leaders moved quickly to formalize their cause. Calls went out for a convention to be held at Washington-on-the-Brazos, where delegates from across Texas would decide the future of the rebellion. Though some still favored reconciling with Mexico under a restored federal constitution, most now saw independence as the only viable path forward. The war had outpaced compromise.

The convention began on March 1, 1836, with fifty-nine delegates in attendance. The group included prominent Anglo settlers, recent immigrants from the United States, and three Tejanos: Lorenzo de Zavala, José Antonio Navarro, and José Francisco Ruiz. Sam Houston, William Wharton, and other key figures in the Texian movement also took part.

On March 2—while Santa Anna’s army advanced toward San Antonio—the delegates adopted the Texas Declaration of Independence, severing all political ties with Mexico. The document cited a long list of grievances, including the abolition of the 1824 Constitution, the dissolution of local legislatures, and the establishment of military rule. It framed the conflict not as a civil war, but as a struggle for natural rights and representative government.

Drafting a New Constitution

After declaring independence, the convention turned to the task of governance. On March 17, 1836, delegates ratified the Constitution of the Republic of Texas, establishing a new national government. The document created a separation of powers among executive, legislative, and judicial branches, closely modeled on the United States system.

The convention elected David Burnet as interim president and Lorenzo de Zavala as vice president. General Sam Houston, already popular among the militias, was officially appointed commander-in-chief of the Texian forces. With Santa Anna’s army closing in, the new government hastily adjourned and dispersed. Officials fled east to avoid capture, beginning a period of disarray known as the Runaway Scrape.

Despite the chaos, the core institutions of a breakaway republic had been established—at least on paper. What had begun as a decentralized resistance movement had now become a formal declaration of nationhood.

Santa Anna’s Offensive

In early 1836, President Santa Anna launched a sweeping military campaign to crush the rebellion in Texas. He personally led an army of more than 6,000 troops across the Rio Grande, determined to retake the territory and make an example of those who resisted. His strategy was uncompromising: treat the insurgents not as wayward citizens, but as pirates deserving of no quarter.

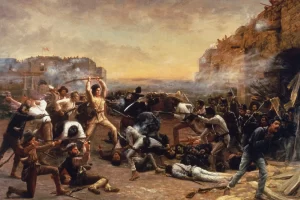

The first target was San Antonio de Béxar, where a small Texan garrison—roughly 220 to 250 men—held the former mission complex known as the Alamo. Commanded jointly by William B. Travis and James Bowie, with the later arrival of famed frontiersman David Crockett and his Tennessee volunteers, the defenders worked to strengthen the compound’s defenses in anticipation of a Mexican advance.

The Alamo’s thick adobe and stone walls, originally built for religious and agricultural purposes, were poorly suited to withstand sustained artillery fire, but the Texans improvised. They mounted cannons along the perimeter, built makeshift palisades to block breaches, and reinforced existing walls with earthworks, timber, and rubble. Supplies of food, ammunition, and powder were limited, and Travis sent repeated dispatches requesting reinforcements, warning that the garrison could not hold out indefinitely.

Despite these limitations, morale among the defenders remained high, bolstered by their shared belief in the cause of Texan independence. They knew they were outnumbered but hoped that their resistance might buy time for Sam Houston’s army to organize or for additional volunteers to arrive. On February 23, 1836, Mexican forces under President Antonio López de Santa Anna reached San Antonio and began encircling the Alamo. The siege commenced that same day, as the Mexican army established artillery positions and began intermittent bombardment. Over the next 13 days, the Texans endured near-constant pressure, refusing to surrender even as the odds grew increasingly grim.

On March 6, before dawn, Mexican troops launched a full assault. The defenders were overwhelmed. Several waves of attackers were initially repulsed by intense musket and cannon fire from within the walls, but the sheer size of Santa Anna’s force eventually allowed them to breach the defenses at multiple points. Fierce hand-to-hand combat followed in the courtyard and barracks. All were killed in the battle or executed afterward, including Travis, Bowie, and Crockett. A few civilians—mostly women, children, and enslaved persons—were spared and released to carry word of the defeat.

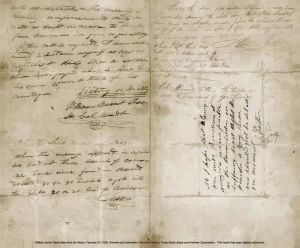

“The enemy has demanded a surrender at discretion, otherwise, the garrison are to be put to the sword, if the fort is taken. I shall never surrender or retreat. I am determined to sustain myself as long as possible and die like a soldier who never forgets what is due to his own honor and that of his country — Victory or Death.”

Letter of Lt. Col. William Travis, Commandant of the Alamo, February 24, 1836

Though a tactical victory for Mexico, the Battle of the Alamo resulted in heavy Mexican losses—about 600 killed or wounded by cannon fire, gunfire, and in hand-to-hand fighting. That was a substantial number, given that Santa Anna’s army in Texas numbered only a few thousand. The use of mass assault tactics against entrenched Texan artillery and riflemen secured the fort, but amplified the Mexicans’ losses.

Moreover, the attack backfired politically. the Alamo defenders’ heroic last stand inspired and inflamed the rebellion. “Remember the Alamo” became a rallying cry for Texian forces and helped frame the conflict in stark moral terms: liberty versus tyranny, defiance against brutality.

The Goliad Massacre

While Santa Anna was sieging the Alamo, a second column of Mexican troops under General José de Urrea moved along the Gulf Coast. His forces engaged and defeated scattered Texian detachments at San Patricio, Refugio, and Agua Dulce. The most consequential encounter came at Goliad, where Colonel James Fannin had assembled a poorly supplied force of about 400 men at Presidio La Bahía.

Fannin had been ordered to retreat to Victoria and link up with Sam Houston’s army, but delayed too long. On March 19, Urrea’s cavalry intercepted the Texans on open ground near Coleto Creek. After a day of fighting and heavy casualties, Fannin surrendered under the belief that his men would be treated as prisoners of war.

Instead, by order of Santa Anna, the captured Texans were executed. On March 27, Mexican soldiers marched Fannin’s men out of the fort in small groups and shot 342 of them to death.4 A few escaped; others were spared by sympathetic officers. The massacre shocked observers and further radicalized the Texian cause.

Among those spared was a group hidden by Francisca Álvarez, the wife or companion of a Mexican officer stationed at Goliad. Remembered as the “Angel of Goliad,” she is credited with intervening on behalf of several Texian prisoners, shielding them from execution. Though few details of her actions are known with certainty, accounts from survivors consistently honored her compassion. Her quiet defiance stood in contrast to the brutality of the massacre and became a symbol of humanity amid the violence of the revolution.

Civilian Flight and Texian Retreat

News of the Alamo and Goliad triggered widespread panic. Thousands of settlers—mostly women, children, and enslaved persons—fled eastward in a chaotic evacuation known as the Runaway Scrape. Farms and towns were abandoned. Roads became impassable. Food and supplies ran short. Many fell ill or died along the journey. The new Texian government, now headquartered in Harrisburg, was in disarray.

Sam Houston, meanwhile, struggled to assemble a viable army. Most men had volunteered for short service, and desertion was common. With little ammunition, few provisions, and unclear support from the civilian government, Houston avoided direct confrontation. Instead, he conducted a slow retreat eastward, training his men and waiting for the right opportunity to strike.

To Santa Anna, it seemed the rebellion was collapsing. But his pursuit of Houston’s scattered forces would soon lead him into a fatal miscalculation.

Santa Anna’s Blunder

By mid-April 1836, Santa Anna believed victory was within reach. The Texian government had fled east, Houston’s army was retreating, and Mexican forces controlled most key positions west of the Brazos River. But in his haste to secure a final blow, Santa Anna overextended his lines and fatally divided his army.

While General Vicente Filísola remained with the bulk of the Mexican force, Santa Anna pushed ahead with about 1,300 troops to intercept the Texians near the confluence of the San Jacinto River and Buffalo Bayou. Houston, now commanding around 900 men—bolstered by two recently arrived cannons known as the Twin Sisters—moved to meet him.

On April 20, the two armies exchanged fire in a brief skirmish. Santa Anna assumed Houston would stay on the defensive and planned a full assault for the following day. Confident and exhausted, he allowed his men to rest on the afternoon of April 21. No fortifications were constructed. Guards were lax. The Mexican camp was exposed.

That afternoon, Houston ordered an attack.

The Battle of San Jacinto

At around 4:30 p.m., the Texians emerged from the tree line and launched a full assault on the Mexican position. Taken by surprise, Santa Anna’s troops had little time to form ranks. The Texians shouted “Remember the Alamo!” and overran the Mexican Army perimeter and into the camp.

The fighting lasted less than twenty minutes. Mexican resistance collapsed almost immediately, and the aftermath turned into a rout. Hundreds of soldiers were killed or captured as they fled through the marshy terrain. Others drowned in the bayou. Houston was wounded in the leg, but his army had achieved a total victory. After the battle, Houston penned this account of the action:

“The Artillery advanced and took station within two hundred yards of the Enemy’s breastwork and commenced an effective fire with grape and canister. Col. Sherman, with his regiment having commenced the action upon our left wing, the whole line at the center and on the right, advancing in double quick time, sung the war cry ‘Remember the Alamo,’ received the Enemy’s fire, and advanced within point-blank shot before a piece was discharged from our lines.

“Our line advanced without a halt, until they were in possession of the woodland and the Enemy’s breastwork. The right wing of Burleson’s and the left of Millard’s taking possession of the breastwork, our artillery having gallantly charged up within seventy yards of the Enemy’s cannon, where it was taken by our troops.

“The conflict lasted about eighteen minutes from the time of close action until we were in possession of the Enemy’s encampment, taking one piece of cannon (loaded), four stand of colors, all their camp equipage, stores, and baggage. Our cavalry had charged and routed that of the Enemy upon the right and given pursuit to the fugitives, which did not cease until they arrived at the bridge…

“The conflict in the breastwork lasted but a few moments; many of the troops encountered hand-to-hand, and not having the advantage of bayonets on our side, our riflemen used their pieces as war clubs, breaking many of them off at the breech. The rout commenced at half past four, and the pursuit by the main army continued until twilight.”

Official battle report of General Sam Houston to David Burnet, Provisional President of the Republic of Texas, April 21, 1836

Of the roughly 1,300 Mexican troops, more than 600 were killed and 300 captured. According to contemporary accounts, many Mexican soldiers who attempted to surrender were killed. Texian losses were minimal—just 11 killed and about 30 wounded. It was the most decisive battle of the revolution.

However, the bulk of the Mexican army remained in the field under Generals Filísola and Urrea. These forces had not yet engaged. Because Santa Anna had split up his forces, these two divisions were not present at San Jacinto when Santa Anna’s camp was overrun.

Historian Stephen Hardin explains, “Careless, or perhaps chauvinistic writers have alleged that Texians defeated the Mexican army at San Jacinto; that they most assuredly did not. The contingent that was decimated along the banks of Buffalo Bayou was but a small portion of the total Mexican army in Texas. Forces under Filosola and Urrea were still a threat, and around nightfall Houston revealed his justifiable fear of an attack.”5

The President Taken Prisoner

Meanwhile, Santa Anna fled the battlefield, but was captured the next day by a Texian patrol and brought before General Sam Houston, who had been wounded in the fighting. Recognizing the political leverage Santa Anna represented, Houston ordered that his life be spared—over the objections of many in the Texian ranks.

Santa Anna, fearful for his life, offered to write to his second-in-command, Vicente Filísola, ordering him to withdraw from Texas. Houston agreed, and the message was delivered.

This put the Mexican general in a quandary. If he continued the offensive, he would put in jeopardy the life of his commander-in-chief and president. He also risked retribution for disobeying the captive dictator, if Santa Anna somehow managed to escape or negotiate his own release. On the other hand, withdrawal meant foregoing a reasonable chance of defeating the still outnumbered and disorganized Texans.

Filísola opted for caution, and began withdrawing the remnants of the Mexican army southward. However, other officers in the Mexican Army viewed this as a dishonorable course of action, and believed that they could have defeated the Texan uprising if the campaign had been continued. According to Stephen Hardin, author of a military history of the Texas Revolution, “Urrea, de la Peña, and others harshly criticized the Italian-born Filisola for submitting to orders issued under duress.”

“Filisola always maintained that, orders or no orders, he had no recourse but to retreat. The heavy rains continued to render movement difficult; supplies were running out; and many soldados were stricken with dysentery. Santa Anna had taken the army so far from its logistical bases that supply lines had broken down. According to Filisola, it was not the Texians who defeated the once proud Mexican army but the ‘inclemency of the season in a country totally unpopulated and barren, made still more unattractive by the rigor of the climate and the character of the land.’ Consequently, Filisola withdrew the Mexican army, not (just) to Béxar, but across the Río Grande.”6

Weeks later, the Mexican government, led by interim president José Justo Corro y Silva, instructed Filísola not to abandon territories already conquered—notwithstanding Santa Anna’s captivity. However, the army was already south of the Nueces, and Filísola, citing the condition of his troops, continued the retreat to Matamoros.

A. Wallace Woolsey, who translated a memoir written by Filísola, notes that he was soon relieved of command: “On June 12, José de Urrea replaced Filísola in general command; Filisola resigned his own command to Juan José Andrade and retired to Saltillo. Filísola was accused of being a coward and a traitor in overseeing the withdrawal of the Mexican troops, and he faced formal charges upon his return to Mexico. The general successfully defended himself before the court-martial and was exonerated in June 1841. Upon his return to Mexico in 1836, Filísola published a defense of his conduct in Texas.”7

In the end, whatever the reasons—poor logistics, disease, or the cowardice of the commanding general—the Mexican forces withdrew beyond the Rio Grande, effectively ending the campaign and leaving Texas in the hands of the separatists.

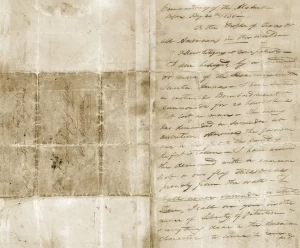

The Treaty of Velasco

Though the military threat had receded, the political future of Texas remained uncertain. Santa Anna, while held as a prisoner of war, signed two “Treaties of Velasco“: a public agreement ending hostilities and ordering the withdrawal of Mexican troops, and a secret accord pledging to recognize Texas independence. However, the treaties were negotiated under duress and ultimately disavowed by the Mexican government.

Attempting to secure his release, Santa Anna also exchanged letters with U.S. President Andrew Jackson. Eventually, the Texans released him, and he returned to Mexico by way of the United States, meeting with Jackson during his journey.

Upon his return to Mexico, however, Santa Anna found his political standing severely damaged. He was ousted from power and forced into temporary exile. Although he would return to power in later years, the defeat in Texas marked a lasting blow to his reputation.

Though fighting began in October 1835 and effectively ended by April 1836, the political status of Texas remained contested for years. Mexico never formally recognized the Republic of Texas, despite the Treaties of Velasco signed by Santa Anna after his capture. It was not until after the Mexican-American War, after Texas had joined the United State, that Mexico officially ceded Texas.

Aftermath of the Revolution

With the fighting halted, Texian leaders moved quickly to consolidate control. David Burnet’s provisional government resumed its functions and began seeking international recognition for the new republic. Elections were held under the new constitution, and Sam Houston was overwhelmingly chosen as the first president.

The new government faced enormous challenges. Many settlements had been abandoned during the Runaway Scrape, trade and agricultural production remained disrupted, and the fledgling economy struggled to recover. The war had also displaced many Tejano residents, especially in contested areas like San Antonio, raising uncertainty about land rights, property claims, and political allegiance.

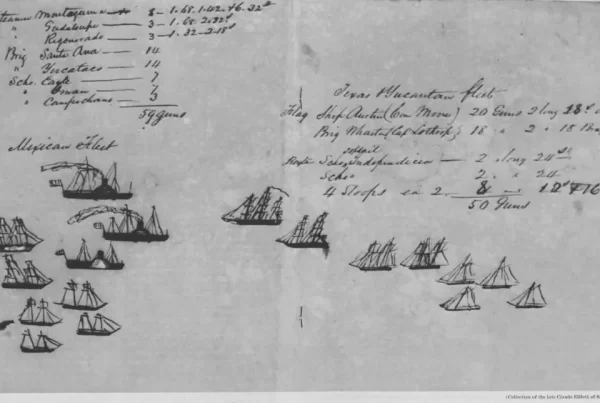

Additionally, although the immediate military threat had receded, Mexico’s refusal to recognize independence kept the specter of renewed invasion ever present. Mexico still had a larger army than the Texan one—even after San Jacinto—and it had better equipment, professional officers, and a more coherent logistical and financial framework undergirding it.

Texas, by contrast, struggled to organize and equip its revolutionary army, before and after San Jacinto. Historian H.W. Brands explains,

“Houston never succeeded in shaping his men into a regular army. From the beginning of the Texas revolution to the end, the rebel troops were irredeemably democratic. This was hardly surprising in an age that made a mantra of democracy, and on a frontier where the democratic ethos was especially pervasive. But it drove Houston to distraction and almost despair. And it nearly cost Texas the revolution. In real armies, authority flows from the top down; in the Texas army it bubbled from the bottom up… But Houston never stopped trying to make soldiers from his men…”8

Nevertheless, this volunteer army—hastily assembled and often disorganized—had defeated a powerful military regime, forcing its troops to withdraw southward—at least temporarily. (Mexican troops later returned, in the 1840s, but only briefly). With the withdrawal of Mexican forces, a new constitution in place, and a provisional government in control, Texans had secured de facto independence.

Who Benefited—and Who Didn’t

The revolution marked a sharp break from the centralized authority of Santa Anna’s government and the beginning of a new political order. The Republic of Texas, declared in March and made real in April, drew heavily from American constitutionalism and the political culture of the Southern United States. It established a presidential system, provided for direct elections, and guaranteed common law rights such as trial by jury,

Still, the new republic was not equally inclusive. Though Tejano leaders like Lorenzo de Zavala and Juan Seguín played vital roles in the revolution, many would soon be marginalized by rising Anglo political dominance. In the decades that followed, Tejano communities faced discrimination and episodes of violence, as Anglo settlers consolidated control over land, politics, and law enforcement.

Enslaved Black Texans remained in bondage under a constitution that forbade emancipation and barred free Black people from residency without legislative permission. Indian nations, already under pressure before the war, came into conflict with the new republic and its citizens, as the westward Anglo settlement accelerated after independence.

Women, meanwhile, remained excluded from political life. Like their counterparts in both Mexico and the United States, they could not vote or hold office.

In the years that followed, Texas struggled with internal divisions, debt, and persistent questions about its long-term viability. The republic endured for nearly a decade before being annexed by the United States in 1845.

Today, Texas schoolchildren learn about the revolution of 1836 as a unifying origin story—one rooted in defiance of tyranny, the assertion of local self-rule, and the vision of a separate destiny for Texas.

Sources Cited

- Letter of Stephen F. Austin to Thomas F. Leaming, April 20, 1833. ↩︎

- Noah Smithwick and Nanna Smithwick Donaldson, The Evolution of a State, or, Recollections of Old Texas Days (Austin, TX: Gammel Book Company, 1900), 101 ↩︎

- Smithwick, 102. ↩︎

- Estimates of the death toll of the Goliad Massacre vary from about 300-400. The precise figure of 342 is given by the long-time curator and historian of the Alamo, Richard Bruce Winders, in his article “’This Is A Cruel Truth, But I Cannot Omit It’: The Origin and Effect of Mexico’s No Quarter Policy in the Texas Revolution,” Southwestern Historical Quarterly 120 no. 4, April 2017. ↩︎

- Stephen L. Hardin, Texian Iliad: A Military History of the Texas Revolution, 1835–1836 (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1994), pg. 216. ↩︎

- Ibid., pg. 216. ↩︎

- A. Wallace Woolsey, “Filisola, Vicente,” Handbook of Texas Online, Texas State Historical Association, published 1952, updated April 7, 2016, https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/filisola-vicente. ↩︎

- H.W. Brands, Lone Star Nation: How a Ragged Army of Volunteers Won the Battle for Texas Independence — And Changed America. (New York: Doubleday, 2004), pg. 284. ↩︎

📚 Curated Texas History Books

Dive deeper into this topic with these handpicked titles:

- The Raven: A Biography of Sam Houston

- Lone Star Nation: The Epic Story of the Battle for Texas Independence

- Women and the Texas Revolution

- Texian Iliad: A Military History of the Texas Revolution, 1835-1836

- New Orleans and the Texas Revolution

Texapedia earns a commission from qualifying purchases. Earnings are used to support the ongoing work of maintaining and growing this encyclopedia.