The Texas Convention of 1833 met at San Felipe de Austin from April 1 to April 13, 1833, bringing together fifty-six delegates from across Mexican Texas. The gathering followed the earlier Convention of 1832, whose petitions for relief from immigration restrictions, tariff enforcement, and other grievances had been ruled illegal and left unaddressed.

Meeting at a moment of political transition in Mexico, the delegates of 1833 repeated many of the earlier requests but also went further, preparing a draft state constitution and seeking separate statehood for Texas within the Mexican federation. Although reformist rather than revolutionary, the convention became an important exercise in collective political organizing and helped to shape a developing Texian political identity in the years before the revolution.

Background: From Anahuac to San Felipe

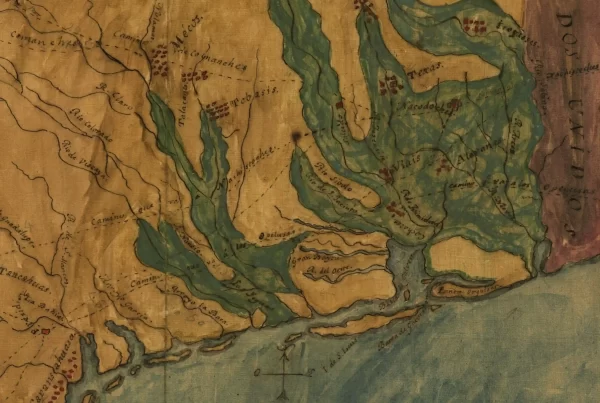

The roots of the convention lay in the unsettled political climate of Mexican Texas during the early 1830s. Mexico, after its independence from Spain, adopted the Constitution of 1824, which created a federal republic. Texas was not established as a separate state but instead merged with Coahuila to form Coahuila y Tejas, with its capital first in Saltillo and later in Monclova. This arrangement left Texas without direct control over its own institutions, and communication across such a large territory proved difficult.

As Anglo-American immigration increased, tensions grew between colonists and Mexican authorities. The Law of April 6, 1830, sought to curb further immigration from the United States, imposed customs duties, and restricted settlement patterns. The measure angered both Anglo settlers and many Tejanos, who resented interference with local autonomy and commerce. Enforcement of customs regulations soon brought matters to a head at the port of Anahuac, where Colonel Juan Davis Bradburn’s garrison detained settlers and provoked widespread unrest. The Anahuac Disturbance of 1832, followed by a clash between Texian settlers and Mexican troops at Fort Velasco and the adoption of the Turtle Bayou Resolutions, led Texians to declare their support for Antonio López de Santa Anna, then seen as a liberal federalist opposing centralist president Anastasio Bustamante.

Out of this turbulence came the Convention of 1832, the first broad political meeting of Anglo-Texans. Meeting at San Felipe de Austin in October 1832, delegates adopted resolutions requesting tariff exemptions, immigration reform, the donation of lands for bilingual schools, militia organization, and, in a controversial move, separate statehood for Texas. Stephen F. Austin presided, while William H. Wharton was chosen to present the resolutions to Mexican authorities. Yet Tejano participation was absent—San Antonio de Béxar and Victoria declined to send delegates—and the political chief Ramón Músquiz declared the proceedings unauthorized and illegal. The petitions were never forwarded, and Austin himself considered the push for statehood premature.

The failure of 1832 left many settlers frustrated. By the spring of 1833, with Santa Anna installed as president of Mexico and local impatience mounting, a second convention was called. This time San Antonio sent delegates, including James Bowie, and the leadership shifted from Austin’s moderation to younger figures prepared to press further demands.

Proceedings of the Convention of 1833

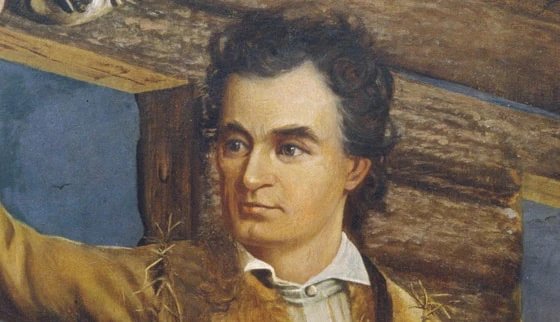

The Convention of 1833 opened on April 1, coinciding with Santa Anna’s inauguration in Mexico City. Fifty-six delegates attended, representing municipalities across Texas. William H. Wharton, described by historian William C. Davis as a “known hothead,” was elected president, a choice that signaled a departure from the restrained leadership of Austin the year before. Thomas Hastings served as secretary, while prominent delegates included Sam Houston, James Bowie, and David G. Burnet.

Delegates quickly agreed to pursue separate statehood, building on but surpassing the agenda of the 1832 meeting. Austin, in his address, reviewed grievances with the judicial system, inadequate Indian defense, customs enforcement, and the general inaccessibility of the Coahuila y Tejas government. The convention resolved to petition for repeal of the immigration restrictions in the Law of April 6, 1830, to secure tariff exemptions, to improve mail service, and to reform judicial administration.

The most significant work of the convention was the preparation of a draft constitution for Texas as a separate Mexican state. Under Houston’s chairmanship, a committee drew heavily from the 1780 Massachusetts constitution and from state constitutions of Louisiana, Missouri, and Tennessee. The document provided for a governor with two-year terms, a bicameral legislature, and a judiciary with local, district, and supreme courts. It included a detailed bill of rights guaranteeing trial by jury, habeas corpus, freedom of the press, and protection against excessive bail and cruel punishments. Although some rights echoed American models, others reflected Spanish tradition, such as the prohibition of primogeniture and imprisonment for debt. Delegates also endorsed public education and insisted on a hard-currency economy.

In one of its final acts, the convention adopted a resolution condemning the African slave trade, a move timed to coincide with the arrival of a Cuban slave ship at Galveston Bay. Although slavery itself remained widespread in Texas—often circumventing Mexican law by converting enslaved people into “indentured servants” for 99 years—delegates sought to distance themselves from illegal importations. The resolution was intended to reassure Mexican authorities of Texians’ good faith rather than to challenge the institution of slavery itself.

To Texans, the San Felipe meeting represented legitimate petitioning within the federal system. To Mexican officials, it looked more ominous. Historian T. R. Fehrenbach, in his influential book Lone Star: A History of Texas and the Texans (1968), wrote that “[such] assemblies, so peaceful and so natural to the English-speaking experience and tradition, were entirely extra-legal under Mexican law… [the convention’s petitions] looked to Mexicans precisely like a pronuncamiento, followed by a plan.”1

“Almost all Mexican historians believed that there was always a well-conceived plot to separate Texas from Mexico, and this cannot be entirely denied.”

Although many American settlers in Mexico held no revolutionary aspirations, the delegations at the 1833 convention included men who “had either lost confidence in Mexico, or had never had any. Among these were Wharton, David G. Burnet, and a newcomer who had merely drifted into Texas but who had enjoyed great prominence in Tennessee—Sam Houston. Houston was a known protégé of Andrew Jackson, now President of the United States, and he was made chairman of the constitutional committee of Texas, although he was not even a legal resident. Houstons motivation was to bring Texas eventually into the United States.”2

More moderate leaders, however, remained loyal to Mexico. Foremost among these was Stephen F. Austin — “Don Estevan” as the Mexicans called him — empresario and founder of the largest Anglo-American colony in East Texas. Austin, who presided over the convention, still believed that Texas could prosper as a federal state within the Republic of Mexico.

Under the influence of the moderates, the resolutions of the Convention of 1833 included emphatic professions of loyalty to the Mexican republic and constitution. Certain appeals for the institution of non-Mexican political practices, however, such as the right to a jury trial, conflicted with these professions of loyalty to Mexican law and the Mexican republic.

Austin’s Mission to Mexico City

When the convention adjourned on April 13, it selected Austin, Juan Erasmo Seguín, and Dr. James B. Miller to present the petitions in Mexico City. Seguín convened a series of meetings in San Antonio from May 3 to 5 to discuss the resolutions. While he personally favored statehood, many local leaders preferred simply to move the capital of Coahuila y Tejas to Béxar, and others condemned the convention as illegal.

In the end, Seguín declined to go to Mexico City, and Miller, a physician, opted to stay to help deal with a cholera epidemic, leaving Austin to travel alone. Austin arrived in Mexico City on July 18, 1833, only to find Congress adjourned by the epidemic and distracted by political turmoil. Vice President Valentín Gómez Farías pursued federalist reforms that unsettled the army and clergy, while Santa Anna withdrew from daily governance. Delays mounted, and Texian impatience grew. In October, Austin wrote to San Antonio officials urging that Texans consider forming a state government even without Mexican approval, signing it “God and Texas.” Intercepted by unsympathetic officials, the letter was forwarded to state authorities.

Austin was arrested in December 1833 on suspicion of treason and remained imprisoned through most of 1834, only returning to Texas in July 1835. The episode transformed his outlook: once the foremost advocate of cautious cooperation, he returned convinced that the path forward was narrowing. Mexican authorities, meanwhile, sought to placate Texians by granting several concessions. Trial by jury was introduced, English authorized as a second official language, and four new municipalities created: Matagorda, San Augustine, Bastrop, and San Patricio. An American immigrant was appointed Attorney General. Austin himself admitted that “every evil complained of has been remedied,” though the memory of his imprisonment overshadowed these concessions.

From Reform to Revolution

The Convention of 1833 marked a turning point in the political development of Texas under Mexican rule. It was not the first collective assembly of settlers, but it was the most ambitious, producing a full state constitution and presenting a coherent set of petitions to the national government. It also demonstrated that Texians could organize across municipalities and draft institutions in common, an experience that would prove essential in later revolutionary assemblies.

In hindsight, the substance of the consultations of 1832-1833 mattered perhaps less than the process by which Texans learned to deliberate and to speak as a unified body. The convention gave Texans practice in drafting constitutions, electing leaders, and articulating rights in written form. When revolution came in 1835–36, this experience was readily adapted to the Consultation of 1835 and the Convention of 1836, which adopted the Declaration of Independence and Constitution of the Republic of Texas. In that sense, the Convention of 1833 stood as the bridge between reformist and revolutionary currents at the end of the era of Mexican rule in Texas. It was a formative moment in the making of a Texian political identity.