The Constitution of 1845 stands as a foundational legal instrument in the history of Texas, marking the formal transition from an independent republic to a constituent state within the United States. Drafted by a convention of delegates in the summer of 1845 and ratified by popular vote, the document functioned as the supreme law of the State of Texas until the secessionist constitution of 1861.

The 1845 Constitution is widely regarded by legal scholars and historians as one of the most coherent, structurally sound, and jurisprudentially mature constitutions in Texas history. It reflected the influence of U.S. constitutionalism, the political philosophy of Jacksonian democracy, and the institutional habits of the former Republic.

This article examines the structural features, legal doctrines, and enduring significance of the 1845 Constitution, with particular attention to its provisions on separation of powers, rights of persons, property regimes, and institutional constraints on public authority.

Political Context

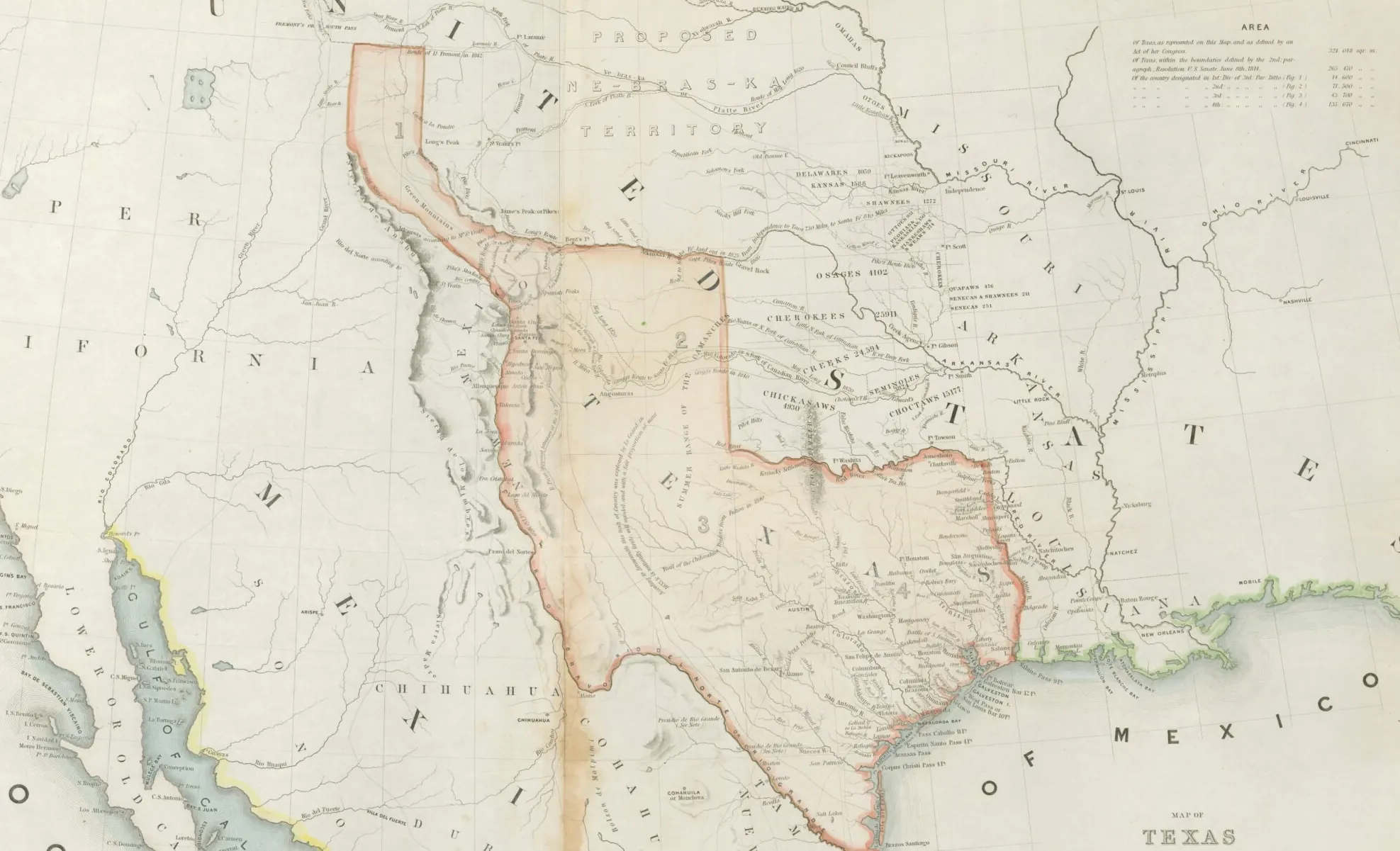

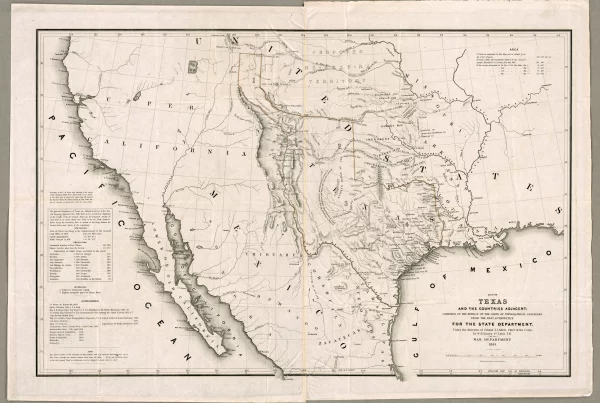

The constitutional convention that assembled in Austin in July 1845 was convened pursuant to the terms of a joint resolution of the U.S. Congress passed earlier that year, offering Texas admission to the Union. Under that resolution, Texas was to draft a state constitution conforming to the principles of a republican form of government as defined in Article IV, Section 4 of the United States Constitution.

The drafters—many of whom had served under the Republic of Texas—drew upon both the 1836 Constitution of the Republic and the constitutions of other Southern states, including the recently adopted Louisiana Constitution, and the constitutions of Kentucky, Tennessee, and Virginia.

The constitution reflected the needs and attitudes of a largely agrarian society, which practiced limited commerce but little large-scale industry or banking. Frederic L. Paxson, a historian of the American frontier, described the drafters of the 1845 as mostly “Jacksonian Democrats”:

“A thorough comparison of the debates of Texas with those of the other states that made themselves Constitutions during the later Jacksonian Period would bring out the point of view of democratic society and Democrats. In Texas, as elsewhere along the frontier, the independence and detachment of society reveal themselves. The absence of large financial interests shows itself in the simple provisions on banking and incorporation. [By contrast,] New York in [its constitution of] 1846, presents the reactions of an elaborately organized community in the presence of its debts and its corporations. All the Constitutions of the period show the change that was imminent, as industry swelled in magnitude and enterprises grew in size. But Texas was still a frontier…”1

The convention completed its work in less than three months, submitting the document to the people of Texas, who ratified it by a large majority. It was then accepted by the United States Congress, and Texas was formally admitted to the Union on December 29, 1845.

Separation of Powers

The Constitution of 1845 adhered firmly to the doctrine of separation of powers, explicitly dividing the government into three distinct departments: legislative, executive, and judicial. Article II, Section 1 provided that “no person, or collection of persons, being of one of these departments, shall exercise any power properly attached to either of the others, except in the instances herein expressly permitted.” This categorical command was more than a rhetorical flourish; it manifested in structural constraints and express prohibitions throughout the document.

Legislative Department

The legislative power was vested in a bicameral legislature, composed of a House of Representatives and a Senate. Representatives were required to be citizens of the United States, qualified electors, and residents of the district they sought to represent. Senators were subject to higher age and residency requirements and were elected to staggered four-year terms.

Article III prescribed a biennial meeting schedule and limited the duration of regular sessions to no more than sixty days, absent emergency. Compensation for legislators was fixed and could not be increased during a legislative session. The Legislature was further constrained by detailed procedural requirements, including single-subject rules and requirements for public readings of bills on multiple days.

Executive Department

The 1845 Constitution vested executive authority in a plural structure, reflecting both the Jacksonian commitment to limited centralized power and the institutional habits of the former Republic. The Governor served as the chief executive officer, elected for a two-year term, with a restriction limiting service to no more than four years in any six-year span. The Governor held the power to veto legislation—including a line-item veto on appropriations—subject to override by a two-thirds vote in each chamber of the Legislature.

However, the Governor was not the sole repository of executive power. The Constitution provided for the independent election of several key officials, including the Lieutenant Governor, Treasurer, Comptroller of Public Accounts, and Commissioner of the General Land Office. The Secretary of State was appointed by the Governor with the advice and consent of the Senate. This distribution of authority created an early version of the plural executive model, preventing consolidation of power and ensuring that core fiscal and administrative functions remained outside the Governor’s direct control.

While this structure appears similar to the modern system under the 1876 Constitution, there are key distinctions. The 1845 executive branch was less fragmented than today’s—fewer statewide officers were independently elected, and term limits were more restrictive. The Governor served shorter terms and was barred from consecutive long-term dominance. Over time, additional offices such as the Attorney General and Agriculture Commissioner were added to the ballot, and term limits were abolished, producing the highly decentralized and politically autonomous executive apparatus that defines Texas governance today.

In its 1845 form, executive power in Texas was thus carefully calibrated: it balanced the need for a functional chief executive with deep skepticism of centralized authority. This framework foreshadowed many features of modern Texas government while remaining a distinct product of its antebellum moment.

Judicial Department

The 1845 Constitution established a unified judiciary composed of a Supreme Court, district courts, and such inferior courts as the Legislature might create. The Supreme Court, consisting of a chief justice and two associates, held appellate jurisdiction only, while district courts exercised general trial jurisdiction.

Structurally, the key change from the constitution of the republic was that district court judges no longer served as associate justice on the Supreme Court. Chief Justice John Hemphill, who drafted the judiciary section, considered this a key flaw of the republic-era judiciary, since it had made it difficult to attain a quorum at the Supreme Court while also administering justice in the districts.

Hemphill also ensured that Supreme Court justices and district judges would serve six-year terms—three times longer than the terms of the governor.2 This change likely reflected concerns over high turnover among judges during the Republic. District court judges were required to reside in their judicial districts and to “hold the courts at one place in each county, and at least twice in each year, in such manner as may be prescribed by law.”3

The 1845 Constitution rejected popular judicial elections, favoring gubernatorial appointment, with Senate confirmation, to preserve impartiality. During the 1845 Convention, “There was suggestion that the judges be made elective instead of appointive by governor and senate, but the more democratic method had little support.”4 The chairman of the convention, former chief justice Thomas Jefferson Rusk, “considered the Judicial Department the most important branch of the government because it was independent of the passions of the people.”5

This design emphasized legal stability over popular accountability. In contrast, modern Texas holds partisan elections for nearly all judges, including those of its appeals courts. While this shift reflects a broader democratic trend, it has also politicized judicial selection in ways the 1845 framers deliberately avoided.

Also, unlike today’s Texas judiciary—which is bifurcated between a Supreme Court for civil matters and a Court of Criminal Appeals for criminal cases—the 1845 system featured a single high court. It also lacked today’s extensive network of intermediate appellate courts and statutory trial courts. The original structure was more compact and centralized, designed to serve a sparsely populated and legally undeveloped state.

Despite these differences, the 1845 judiciary introduced key elements that endure today: a hierarchical court system, published opinions to build precedent, six-year terms, and a clear constitutional basis for judicial power. Its emphasis on structure and judicial professionalism laid the groundwork for Texas’s legal system even as later reforms expanded and democratized the bench.

Bill of Rights

The Constitution of 1845 opened with a detailed Declaration of Rights, drawing heavily from the U.S. Bill of Rights and similar provisions in earlier Southern state constitutions. It affirmed fundamental civil liberties, including freedom of speech, press, assembly, and religion, and prohibited bills of attainder, ex post facto laws, and unreasonable searches and seizures. The right to trial by jury and the privilege of habeas corpus were also expressly guaranteed.

Among its more distinctive provisions, the Constitution required that officeholders acknowledge the existence of a Supreme Being, a theistic clause that would remain in Texas law well into the 20th century.

At the same time, it imposed a strict barrier between clergy and civil government: “No minister of the gospel or priest of any denomination whatever shall be eligible to the office of the Executive of the State, nor to a seat in either branch of the Legislature.”

Advertisement

This prohibition reflected widespread Jacksonian concerns about clerical influence in politics and a Protestant ethos that emphasized lay governance. Though common in 19th-century state constitutions, such provisions have since been rendered unenforceable under modern First Amendment jurisprudence.

The 1845 Declaration of Rights also contained economic and legal protections, including a ban on monopolies, an anti-nobility clause, and safeguards against the abuse of corporate charters. Religious liberty was broadly affirmed, but the state retained the authority to regulate institutions and prevent sectarian dominance in public affairs.

In total, the Bill of Rights section of the 1845 Constitution reflects a complex blend of libertarian principles, Protestant republicanism, and early populist legalism—anticipating many of the enduring tensions in Texas political identity.

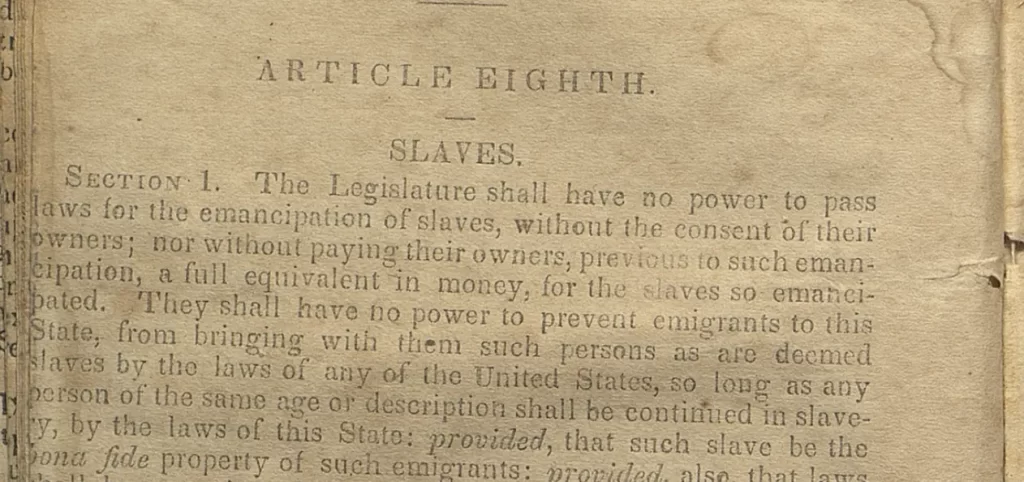

Slavery

Article VIII prohibited the Legislature from emancipating enslaved persons without the consent of the owner and from prohibiting the immigration of slaveholders into the state. Enslaved persons were explicitly treated as legal property, and their status as such was constitutionally protected. The document thus entrenched slavery within the legal order, aligning Texas firmly with the Southern slaveholding states at a time of growing national conflict over the institution.

Homesteads and Community Property

In contrast to its regressive stance on human rights, the 1845 Constitution was relatively advanced in its treatment of certain property protections. It codified the doctrine of separate property for married women, recognizing a wife’s pre-marital and inherited property as distinct from the marital estate. Additionally, it adopted a homestead exemption—protecting a family’s primary residence from forced sale for debt except in limited circumstances. These provisions reflected both frontier conditions and an ethos of economic independence that would persist in Texas law.

Fiscal Restraint and Public Policy Limitations

The framers of the 1845 Constitution, chastened by the Republic’s chronic debt and financial instability, imposed stringent limits on public borrowing and state spending. The Constitution capped the public debt at $100,000, except in cases of war, invasion, or insurrection. It prohibited the state from chartering corporations except by special legislative act, and even then only under limited conditions. Banks of issue were explicitly forbidden.

“In the matter of corporations, Texas in 1845, as most states between the panics of 1837 and 1857, revealed the hostilities that hard times had engendered. The chartering of banks was sweepingly forbidden, in spite of appeals. for moderation and the future. More than this, the original section on banking and corporations was expanded, forbidding any issuance of notes or paper money, and restricting private corporations to such as could secure their chasers by two-thirds vote in the legislature.”6

The Constitution also mandated the establishment of a public school system and authorized the setting aside of land and funds for that purpose. While these provisions would remain largely aspirational during the antebellum period, they represented an early legal recognition of the state’s role in educational development.

Suffrage and Citizenship

The 1845 constitution restricted the right to vote to “free male persons,” age 21 or older, who had resided in Texas for one year and in their district for six months. It forbade U.S. military personnel residing in Texas from voting. It also explicitly excluded “Indians not taxed, Africans, and descendants of Africans.” The Constitution thereby codified a narrow conception of political membership consistent with racial and gender hierarchies of the time.

However, the 1845 constitution struck the word “white” from a draft list of voter qualifications, after debate over whether Hispanics were “white.” Historian Frederic L. Paxson explains, “The debate on the word ‘white’ arose when the Committee on the Legislative reported that electors should include ‘free white males’ as had been the case under the Constitution of 1836. Objection was made to this because of the doubt prevailing among some of the Texans as to the color of the Mexicans.”

“President Rusk supported the motion to strike out ‘white’ and to find a different means of excluding negroes and Indians not taxed from the electorate, because ‘It may be contended that we intend to exclude the race which we found in possession of the country when we came here. This would be injurious to those people, to ourselves, and to the magnanimous character which the Americans have ever possessed.'”

“And Navarro [the only Tejano delegate], speaking through his interpreter, added, ‘that if the word white means anything at all it means a great deal, and if it does not mean anything at all it is entirely superfluous, as well as odious, and, if you please, ridiculous. . . . [It] is odious, captious, and redundant.’ The word was stricken out, and the form of description of electors was made more general.”7

Amendment and Revision

The 1845 Constitution was relatively difficult to amend. Article XIII required amendments to be proposed by a two-thirds vote in each house of the Legislature and then ratified by a majority of the electorate. Constitutional conventions were authorized only by legislative enactment, and only after a majority vote of the people. This rigidity, though intended as a safeguard, would later prove burdensome as the state’s political and economic conditions evolved.

Supersession and Legal Legacy

The 1845 Constitution remained in effect until Texas seceded from the Union and adopted the Confederate Constitution of 1861. It was formally repealed but served as the structural template for subsequent constitutional iterations, including those of 1866 and 1876. Many of its institutional arrangements—the biennial legislature, the plural executive, the homestead exemption, and the strong bill of rights—have persisted, in form or in spirit, in Texas constitutional law.

Legal scholars often regard the 1845 document as a high-water mark in Texas constitutional drafting. Its clear articulation of governmental structure, coupled with fiscal restraint and detailed rights provisions, reflected a maturity of constitutional thought not always evident in later, more politicized charters.

Sources Cited

- Frederic L. Paxson, “The Constitution of Texas, 1845,” The Southwestern Historical Quarterly 18 (1914–1915): pg. 398. ↩︎

- Constitution of the State of Texas (1845), art. IV, § 5, Tarlton Law Library, University of Texas School of Law, https://tarlton.law.utexas.edu/c.php?g=787754&p=5639721. ↩︎

- Constitution of the State of Texas (1845), art. IV, §6. ↩︎

- Paxson, pg. 393. ↩︎

- Michael Ariens, Lone Star Law: A Legal History of Texas (Lubbock: Texas Tech University Press, 2011), pg. 23. ↩︎

- Paxson, pg. 397. ↩︎

- Paxson, pg. 392. ↩︎

📚 Curated Texas History Books

Dive deeper into this topic with these handpicked titles:

- Storm over Texas: The Annexation Controversy and the Road to Civil War

- Lone Star Law: A Legal History of Texas

- Adding the Lone Star: John Tyler, Sam Houston, and the Annexation of Texas

Texapedia earns a commission from qualifying purchases. Earnings are used to support the ongoing work of maintaining and growing this encyclopedia.