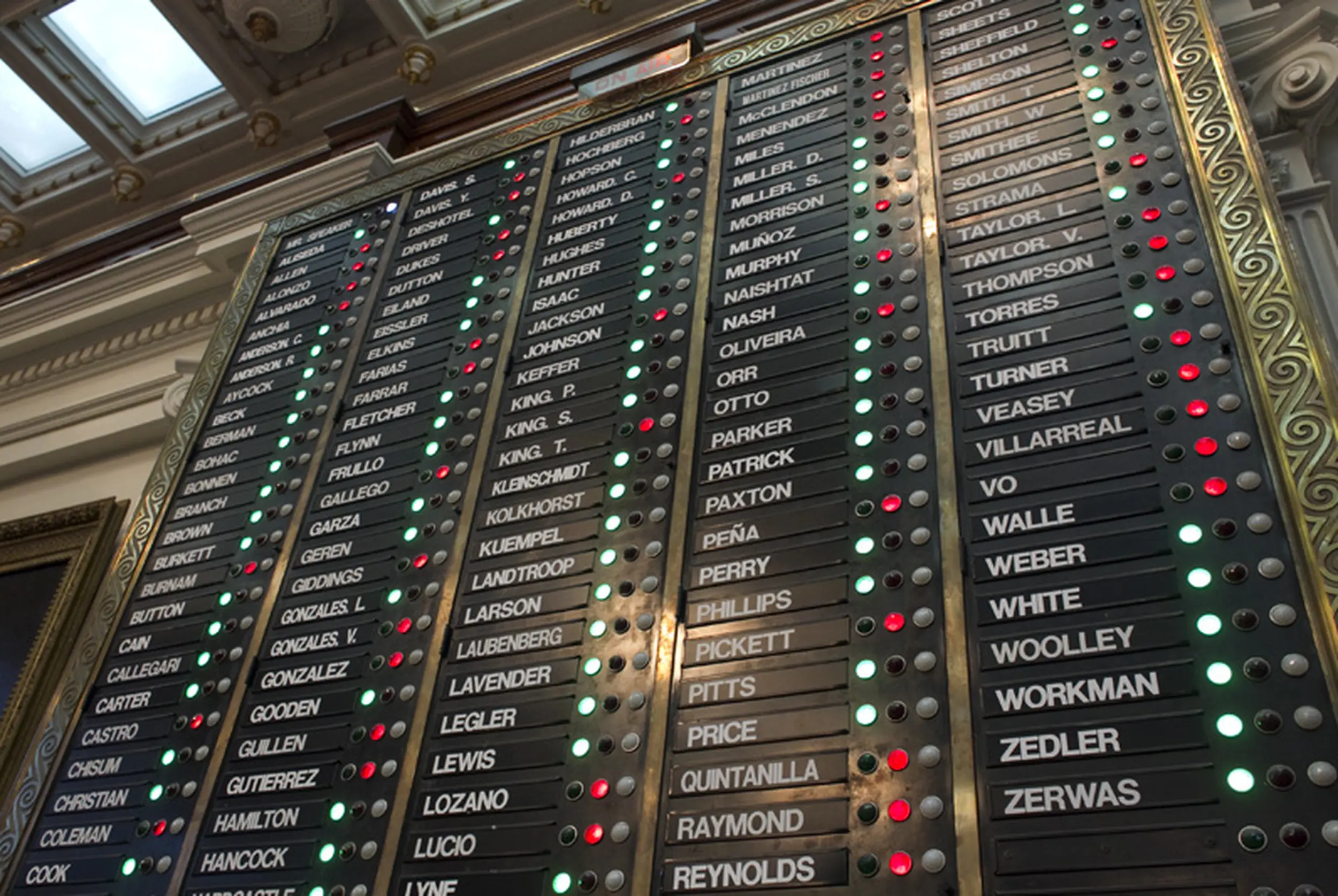

In the Texas House of Representatives, a long-documented practice has drawn criticism for its apparent conflict with basic democratic norms: legislators casting votes on behalf of colleagues who are not physically present. Commonly known as ghost voting, this tradition has at times been tolerated despite clear rules limiting when it is allowed. Its persistence raises critical questions about transparency, accountability, and legislative culture in Texas government.

What Is Ghost Voting?

Ghost voting refers to the act of a legislator casting a vote using the voting machine of another lawmaker who is not at their desk. Although the practice may seem like an outright violation of legislative integrity, it has often been justified by members as a form of collegial convenience—especially when a lawmaker steps away briefly and has already indicated their intent to vote a certain way.

House Rules and Enforcement

Under the House Rules of Procedure, ghost voting is restricted but not absolutely prohibited. According to Rule 5, Section 47:

“Any member found guilty by the house of knowingly voting for another member on the voting machine without that other member’s permission shall be subject to discipline deemed appropriate by the house.”1

The rules of procedure further require that the journal clerk lock the voting machine of any member who is absent or excused during a legislative day. The machine must remain locked until the absent member personally requests its reactivation. However, members normally only report themselves formally absent if they are out of town, so this rule does not exclude ghost voting on behalf of members who are elsewhere on the Capitol premises, but not in the chamber itself.2

To restrict the practice further, while still allowing it in limited circumstances, the House in recent years introduced a rule requiring a member to be, physically present in or near the chamber, effectively prohibiting ‘ghost voting’ when members are in their offices or elsewhere:

“A member must be on the floor of the house or in an adjacent room or hallway on the same level as the house floor, in order to vote.”3

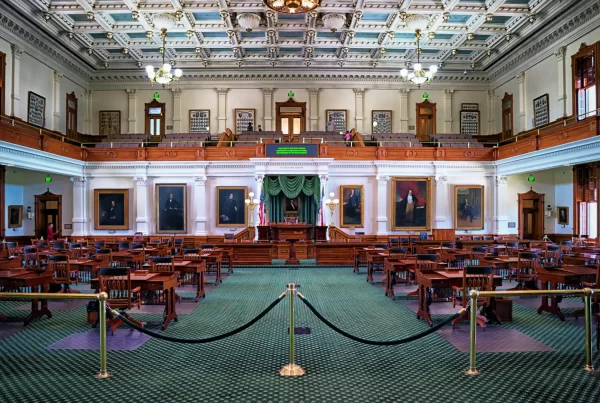

These rules collectively establish that voting on behalf of another member is only permissible when the absent member is physically present on or near the House floor and has given explicit permission. For instance, if a legislator stepped out of the chamber for a phone call, he could ask a colleague to vote for him on an upcoming bill—but only if he remained in a nearby hallway or room.

Despite these clarifications, enforcement has been inconsistent. In many past sessions, voting machines remained unlocked and accessible, allowing fellow members to cast votes with little oversight. Disciplinary actions have been rare, reinforcing a culture of permissiveness.

At one point, a House committee even considered implementing thumbprint verification or other biometric identification systems to prevent unauthorized voting. While the proposal received some attention, it was never adopted—likely due to concerns about cost, logistics, and resistance to major procedural changes.4

Public Scrutiny and Media Exposure

The issue has periodically attracted public attention, particularly when documented by media outlets. Over the years, hidden camera investigations, newspaper exposés, and advocacy group reports have drawn renewed scrutiny to ghost voting, often prompting public outcry and promises of reform.5 Nonetheless, structural and cultural obstacles have hindered lasting change.

One of the most notorious incidents of ghost voting occurred in 1991 when Representative Larry Evans, D-Houston, was recorded as voting on amendments to a congressional redistricting bill. Unbeknownst to his colleagues, Evans had died in his apartment several hours before the voting began.

Institutional Norms and Peer Pressure

The tolerance of ghost voting reflects deeper institutional dynamics. Some lawmakers have described the practice as a professional courtesy—a way to maintain legislative momentum when a colleague steps away briefly to attend to constituent matters, meet with stakeholders, or manage health needs. In fast-paced sessions with dozens of votes occurring in a single day, members may rely on one another to cast expected votes to avoid slowing down proceedings or missing key legislation.

In this context, ghost voting has sometimes been seen not as deception, but as a gesture of trust and mutual accommodation—especially when a member has communicated their voting preferences in advance. Some argue it allows lawmakers to balance their legislative duties with other responsibilities without penalizing their constituents.

However, these informal arrangements also carry risks. Others note that speaking out against ghost voting or refusing to participate in it can lead to political isolation or damage relationships in a chamber where collaboration is critical to getting bills passed. Junior members may feel pressure to conform to unspoken norms, while senior members may expect reciprocal courtesy.

Ultimately, while some defend the practice as a functional adaptation to legislative demands, critics argue that it undermines transparency and reinforces a culture of selective rule enforcement.6

Attempts at Reform

Throughout the years, a handful of members have attempted to curb ghost voting through stricter enforcement of the rules or public condemnation. These efforts have occasionally led to temporary changes in behavior but have rarely resulted in permanent policy changes. The persistence of the practice underscores the limits of internal reform mechanisms in the absence of external accountability.

Comparison to Other States and Congress

Texas is not alone in facing questions about ghost voting or proxy behavior. Some state legislatures, including in Illinois and Pennsylvania, have had their own controversies involving lawmakers casting votes for absent colleagues, though these incidents often led to rule changes or public reprimands.7 In contrast, other states enforce stricter voting protocols and impose real-time electronic attendance verification to prevent such conduct.

In Congress, the U.S. House of Representatives historically required physical presence for votes. However, during the COVID-19 pandemic, proxy voting was temporarily authorized under formal procedures. Unlike Texas ghost voting, congressional proxy votes were openly declared and documented. The practice was later phased out in 2023.8

The comparison highlights that while proxy mechanisms may exist elsewhere, they are typically regulated, transparent, and time-bound—unlike the informal, undocumented nature of ghost voting in Texas.

Constitutional and Ethical Questions

At its core, ghost voting challenges the principle of direct representation. Voters elect individuals to deliberate and cast votes on their behalf—not to delegate those responsibilities informally to others. The practice raises constitutional questions about legislative legitimacy and ethical standards, particularly in a state where legislative rules and decorum carry the force of tradition.

Implications for Legislative Trust

In Texas political life, the practice of ghost voting has elicited varied interpretations. Some view it as a collegial gesture—a reflection of the high-volume, fast-paced nature of legislative work, where dozens of votes may occur in a single day and members occasionally step away for brief meetings, calls, or other duties. In that context, allowing a colleague to vote on one’s behalf, with prior instruction or consent, has been seen by many legislators as a practical accommodation rather than a breach of decorum.

Others, however, have regarded the practice as emblematic of lax enforcement or insufficient safeguards, especially when it appears that a vote was cast for someone not physically present or not recently consulted. Over time, media and watchdogs have highlighted these instances, framing them as examples of broader concerns about transparency and accountability.

The significance of ghost voting in Texas, therefore, has often depended less on formal rule violations and more on evolving expectations—within the chamber and among the public—about presence, representation, and the appearance of procedural integrity.

Sources

- Rules of Procedure of the Texas House of Representatives (2025), Rule 5 Section 47 (pg 108) ↩︎

- Rules of Procedure, Rule 5, Section 46 (pg. 109) ↩︎

- Rules of Procedure, Rule 5, Section 45 (pg. 108) ↩︎

- Texas House Administration Committee, “Hearing Materials on Electronic and Biometric Voting Security,” archival briefing, 2007. ↩︎

- See, for example, investigative coverage from multiple Texas newspapers and watchdog organizations since the 1990s. ↩︎

- Interviews with former and current Texas lawmakers as reported in legislative ethics studies and political journalism accounts. ↩︎

- National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL), “Legislative Ethics Enforcement Overview,” updated 2022. ↩︎

- Congressional Research Service, “Proxy Voting in the House of Representatives: Rules and Precedents,” RL47045 (2023). ↩︎