During the Republic of Texas era, courtrooms were often makeshift spaces, improvised from whatever buildings were available. With few dedicated courthouses constructed in the 1830s and early 1840s, judges and lawyers conducted proceedings in private homes, taverns, churches, or even under trees in favorable weather.

These venues lacked formal architecture or separation of roles—jurors might sit shoulder to shoulder with spectators, and the judge’s bench could be little more than a plank laid across barrels. The absence of court reporters, proper seating, or security gave the proceedings a rough-and-ready character—less solemn than spirited—blending legal formality with the practical improvisation of frontier life.

The new government had to construct a judiciary almost from scratch, adopting a mostly Anglo-American system even as it borrowed elements from the Spanish and Mexican systems. In the decade between independence and annexation, the Republic’s judiciary evolved from a fragmented and improvised system into the backbone of a functioning government.

The early Texas judiciary most frequently dealt with cases of murder, assault, land title, fraud, debt collection, and theft. Cases of gambling (which was illegal) were also common, but often dismissed, as enforcement was lacking and not sufficiently a deterrent.

Defendants could be sentenced to death by hanging, but murderers just as often escaped justice, whether by evading arrest and indictment, or by persuading juries through claims of self-defense or extenuating circumstances. Horse theft, robbery, and certain other offenses were also punishable by death. There were few jails or prisons, and punishments instead involved the death penalty, fines, flogging, or occasionally even branding.

The frontier republic was a violent place, and the new judiciary struggled to enforce laws and court rules uniformly given the prevalence and even widespread social acceptance of violence. According to historian William R. Hogan:

“Texans commonly settled differences by personal encounters, whether by fighting, shooting, stabbing, or dueling. More than two-thirds of the total number of indictments in the district courts were for the crimes of assault and battery, affray, assault with intent to kill, or murder. About 60 percent of the assault and battery (usually fist fighting) cases resulted in convictions, but sentences were light—usually five or ten dollars and costs.”

“Prosecutors in trials for more serious offenses encountered great difficulty in obtaining convictions because juries tended to give serious consideration to pleas of self-defense, the extenuation of unbearable provocation, or the severity of punishments prescribed by law.”1

Spanish & Mexican Legal Foundations

Under Spanish and later Mexican rule, Texas was governed primarily under civil law traditions inherited from continental Europe. Judicial functions were often vested in local officials, such as alcaldes, who combined administrative, executive, and judicial authority. The ayuntamiento (town council) system provided local governance, while state-level appeals flowed to higher courts in Saltillo and Mexico City.

The Mexican Constitution of 1824 and the legal code of Coahuila y Tejas defined this framework, emphasizing codified statutes, limited precedent, and procedures more inquisitorial than adversarial. Legal proceedings were conducted in Spanish, and juries played no formal role. Property disputes, especially over land grants, were central to the administration of justice, and much of the legal record was embedded in notarized archives rather than court opinions.

American Influences

The American-born settlers who had migrated to Texas during the 1820s and 1830s brought with them a markedly different conception of law. Influenced by the Anglo-American common law tradition, many Texans had lived under systems that emphasized jury trials, elected judges, adversarial proceedings, and judicial precedent.

These early Texans hailed from Southern states like Tennessee, Virginia, Alabama, and Georgia, where courts were integral to political life and judges were often prominent figures in local power structures. As tensions with the Mexican government escalated, legal disagreements over language, procedure, and the legitimacy of local authority contributed to broader grievances that culminated in the rebellion against Mexico.

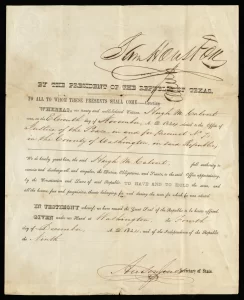

The 1836 Constitution

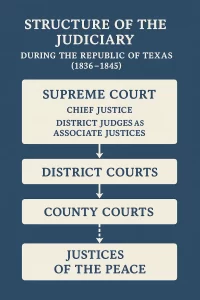

The Constitution of the Republic of Texas, drafted at Washington-on-the-Brazos, reflected this shift in legal orientation. Ratified in March 1836, it established a judiciary that strongly resembled those of the American South. The Constitution created a Supreme Court, district courts, and inferior courts, while enshrining the right to trial by jury and the writ of habeas corpus.

Judges were elected by joint vote of both houses of the Texas Congress,2 and the Supreme Court consisted not of a separate bench but of the chief justice sitting with the district judges as associate justices.3

This arrangement made the Supreme Court a part-time appellate body, and its sessions were infrequent due to travel difficulties and limited infrastructure. In fact, the Supreme Court did not even hold its first session until January 1840, even though the first chief justice and associate justices (district judges) were appointed in 1837.

The republican constitution provided for the division of Texas into “convenient judicial districts, not less than three, nor more than eight.”4 Eventually, seven district courts were established, in addition to one county court per county, and more numerous justice of the peace courts for handling petty civil and criminal cases.

Compared with today’s judiciary, the Republic of Texas judiciary lacked uniform rules of procedure, evidence, and standards of decorum, even years after its establishment. Law books were lacking, legal and judicial training was informal, and court fees and administration varied widely. One reader to a Houston newspaper in 1840 inquired critically,

“Mr. Editor—May we [be] permitted to ask if in the approaching sixth year of a Supreme Court and a Chief Justice, with all of their imposing concomitants of profit and honor, we may look for the adoption of sufficient Court Rules, and the definite settlement thereby of a system of practice at Common Law, in Equity, and of Admiralty, for all the Courts of the Republic? It would seem to be time that there was some concert of action between the different courts, at least of similar jurisdiction;—some practical and uniform lines of demarcation for the government of all the courts of the country, as yet almost as confused, irregular, and unharmonious as at their first organization.”5

By contrast, the Texas judiciary today operates under uniform court procedures codified in the Code of Criminal Procedure, the Civil Practice and Remedies Code, and rules promulgated by the state Supreme Court through a formal rule-making process. While judges in Texas today still have some latitude to adopt local practices and rules in their courtrooms, they lack the freewheeling authority of Texan judges during the republican era.

Another key difference lies in how republic-era courts handled questions of jurisdiction and standing. While these are important matters in court filings and proceedings today, early Texas courts—and citizens—were less concerned with jurisdictional technicalities. Litigants instead generally brought cases to whatever judge was closest at hand.

The constitution of the republic had been written in haste, and the Texan Congress did not immediately enact statues governing the work of the judiciary. Courts functioned on sparse legal scaffolding for many years. Consequently, early judges frequently stretched or assumed jurisdiction in order to keep proceedings moving. They were concerned with bringing order to a violent and rather unruly settler society, and they knew they were unlikely to be challenged on jurisdictional questions, whether by litigants or by higher courts. In general, “The population of the fledgling Republic didn’t concern itself with questions of jurisdiction,”6 writes Ken Wise, an appellate justice, historian, and host of the Wise About Texas podcast.

District Courts

District courts formed the backbone of the Republic’s judiciary. Each district judge presided over multiple counties, riding circuit to hold court in various locales. These judges wielded extensive authority, hearing both civil and criminal cases, overseeing probate matters, and handling appeals from local justices of the peace.

Given the absence of intermediate appellate courts and the rarity of Supreme Court review, district judges often had the final word. Their rulings helped shape Texas legal culture, even if few formal opinions were published.

District Courts had broad jurisdiction over both felony and misdemeanor criminal cases, as well as civil cases where the value involved was $100 or more.

By contemporary standards, the district courts lacked judicial decorum and formalism. According to historian William Ransom Hogan, the district courts “not only were the scene of the most important litigation, but also were the centers of a certain amount of social life.” In his social history of the republic, he offered a colorful portrait of court life:

“While [the district courts] were in session, litigants, witnesses, prospective jurors, friends of persons on trial, spectators, gamblers, and an occasional peddler crowded the courtroom, grogshops, and streets. Gambling games flourished in the shady back rooms of stores and grogshops. At night the barristers engaged in storytelling in which they not only enlarged upon the comic incidents of current and past trials, but also told anecdotes of hunters, preachers, schoolmaster, gamblers, and swindlers.”

“Sharp observers and magnificent storytellers, the veterans of the bench and bar created whole styles of stories about frontier types as well as about themselves. Doubtless the best of these tales were related at suppers at which the lawyers sometimes got drunk en masse. Indeed, court weeks furnished one enthralling substitute for formalized amusements.”

Even in the courtroom, people sometimes smoked, chewed tobacco, or showed up drunk. It was not unusual for lawyers or litigants to behave rowdily, insult or threaten judges, or bring weapons into the courtroom. One British visitor in the 1840s recorded with mild shock that he had seen a judge in Galveston chewing tobacco while resting his feet on his desk, while the district attorney and other lawyers gave speeches, chewed tobacco, smoked, and whittled.7

In this context, judges were rough and plainspoken, if not always educated in the law. Even so, judges tried to curb egregious conduct and sometimes fined or jailed lawyers or litigants for disrespecting the court. 9 Judges, like other prominent men on the frontier, were known to carry a pair of pistols and sometimes Bowie knives or similar large side knives for close-quarters defense.

Lower Courts

The Republic’s constitution stated, “There shall be, in each county, a county court, and such justices’ courts as the Congress may from time to time establish.”10 Additionally, the constitution established, in connection with the judiciary, one sheriff, one coroner, and “a sufficient number of constables” per county. These local officials and magistrates were chosen in elections every two years (by contrast, sheriffs and constables today serve four-year terms). Justice of the peace and sheriffs required, after winning election, a formal commission from the president of the republic. The republic thus allowed local communities to choose their own lawmen and lower court judges, while tying their authority symbolically, through an act of commissioning, to the central state apparatus.

Justices of the peace and county judges acted not only as neutral arbiters in court cases but as law enforcement officers in their own right. The constitution stated, “The judges, by virtue of their offices, shall be conservators of the peace, throughout the republic.”11 Texans of the period would not have identified with the aloof judicial culture of today. Instead, judges were meant to be active representatives of the state, the embodiment of state authority, working actively to preserve law and order in close coordination with armed lawmen.

During the republic, county government and the judiciary were virtually synonymous. The only enumerated powers of county governments in the constitution were judicial functions, law enforcement, and conducting elections. This system established county judges as the foremost officials in local government—an arrangement that would later evolve into Texas’ unique practice today of still calling county executives “judges,” unlike most other states were they are the county “executive” or “mayor.”

In both the lower courts and the district courts, judges sometimes took fees for court services, such as executing deeds or performing weddings. Since there was no statutory schedule of fees or system-wide rules, judges chose for themselves what was an appropriate amount to charge. They also sometimes failed recuse themselves in cases where they had an interest. Historian Ken Wise write, “Conflict of interest rules as well as anything resembling a code of judicial conduct were non-existent in the new Republic.”12

Law on the Frontier

Administering justice in the Republic of Texas was a challenging logistical endeavor. Court sessions were held in makeshift venues, court records were often incomplete or lost, legal texts were scarce, the Republic had few statutes or rules on the books, and practitioners relied heavily on memory, habit, and precedent imported from other states. Judges and lawyers traveled long distances, sometimes under threat of Indian raids or banditry.

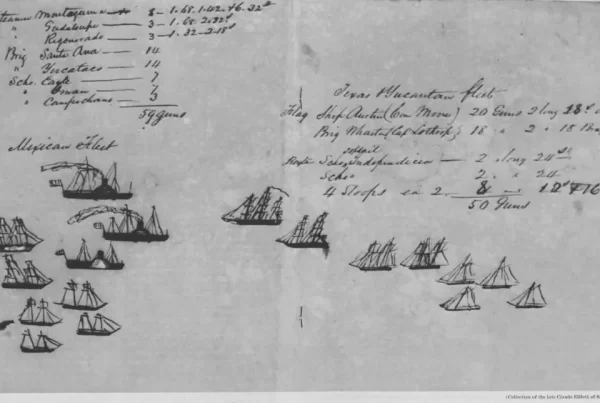

During one sitting of a district court in San Antonio, the judge and lawyers were captured by an invading Mexican force under General Adrian Woll, which launched a surprise attack on Texas in 1842. As a result, lawyers were scarce in San Antonio for a period, and courts in neighboring counties suspended operations.

While the Constitution declared English to be the language of the Republic, many residents continued to speak Spanish, and disputes over earlier Mexican land grants required some familiarity with Spanish legal documents. Despite the formal abandonment of civil law, its legacy remained embedded in property law and the day-to-day functioning of courts, especially in San Antonio and South Texas.

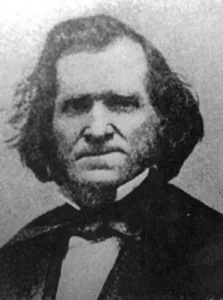

The Republic’s Most Prominent Jurist

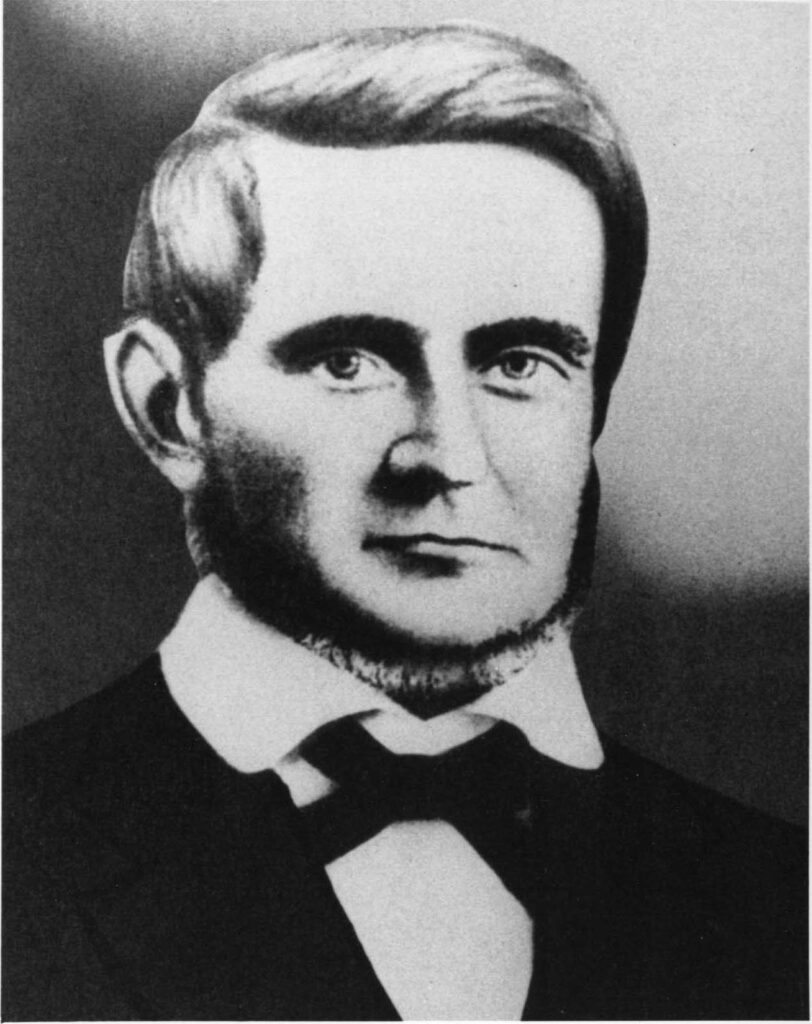

Notable among the early jurists was John Hemphill, who sought to harmonize Spanish legal principles with emerging Anglo-American norms. Born in South Carolina in 1803 and trained in the common law tradition, Hemphill came to Texas in the 1830s and quickly gained prominence for his legal intellect and cultural adaptability. Before becoming chief justice, he served as a district judge.

Hemphill served as chief justice of the Supreme Court of Texas during both the Republic and statehood eras, and his legal opinions displayed a pragmatic willingness to respect existing Mexican legal traditions, especially in areas like community property and water rights. In doing so, he helped lay the groundwork for a uniquely Texan legal identity that blended civil and common law elements—a legacy still visible in modern statutes and judicial process.

One of his most influential decisions upheld community property rights inherited from Spanish law, arguing they were consistent with republican values and beneficial to marital equity. Hemphill also played a crucial role in cases dealing with land titles and water law, often referencing Spanish legal treatises and colonial-era statutes. His rulings emphasized legal continuity and stability in the wake of independence, shaping a Texas judiciary that was distinct from other Southern states and more accommodating of hybrid legal traditions.

Political Pressures & Qualifications

While the judiciary was intended to be independent, it remained deeply intertwined with politics. Many judges were appointed based on military service, political connections, or loyalty to prominent factions.

Judicial qualifications were uneven, and some appointees had little formal legal training. Court backlogs were common, and the legislature occasionally intervened in judicial matters, including salary disputes and jurisdictional changes. Political instability, financial hardship, and shifting population centers all undermined efforts to build a consistent and respected judiciary.

The Struggles of the Supreme Court

The Supreme Court, in particular, struggled to assert itself as a meaningful appellate authority. Its membership fluctuated depending on the availability of district judges, and it lacked the institutional autonomy of high courts in established states.

Nonetheless, it handled a modest docket of appeals and constitutional questions, gradually accumulating precedents that would inform state jurisprudence after annexation. In 1841, a constitutional amendment sought to stabilize the judiciary by fixing terms and clarifying jurisdiction, but problems persisted until the transition to statehood.

Common Legal Disputes and Enforcement Challenges

Throughout the Republic period, courts dealt with a recurring set of legal issues: property claims arising from Spanish and Mexican grants, debts and promissory notes, land fraud, theft, and violence. Criminal cases often reflected the volatile nature of life on the frontier, and law enforcement was uneven at best.

The Republic lacked a formal penal system until late in its existence, and many sentences were carried out locally or commuted due to practical constraints. Justice could be arbitrary, especially in rural areas where local powerbrokers dominated proceedings.

Comparisons to the American South

Comparison with other Southern states reveals both convergence and divergence. Like courts in Mississippi or Alabama, Texas courts emphasized adversarial proceedings and jury trials. However, the Republic’s courts lacked the institutional maturity and formal legal community of those states.

Texas judges enjoyed broader discretion, and courtroom practice was often looser. The absence of appellate supervision and the difficulty of access to formal legal materials gave district judges extraordinary influence. Yet, despite these challenges, the judiciary succeeded in creating a basic framework of order and legitimacy for the young nation.

Toward Statehood & Judicial Reform

The Republic’s judicial system never fully escaped the tensions between improvisation and formalism, between political patronage and legal professionalism. Yet the judicial experience of the Republic of Texas foreshadowed many features of Texas law that would persist into the statehood era. The large number of judicial districts, the hybridization of legal traditions, and the preference for local trial authority over centralized appellate review all became hallmarks of the state system.

The transition to statehood in 1845, marked by the adoption of the Constitution of 1845, brought significant structural reforms. The Supreme Court was reconstituted as a permanent body with a fixed bench, and the judiciary gained clearer jurisdictional boundaries. Popular election of judges, a feature absent in the Republic, would later become a defining characteristic of the Texas judicial system.

Sources Cited

- William R. Hogan, The Texas Republic: A Social and Economic History (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1946), pg. 260. ↩︎

- Constitution of the Republic of Texas Article IV, § 9 ↩︎

- Constitution of the Republic of Texas Article IV, § 7 ↩︎

- Constitution of the Republic of Texas, Article IV, §2 ↩︎

- Houston Telegraph and Texas Register, December 30, 1840 ↩︎

- Ken Wise, “District of Brazos: The Republic’s Secret Court,” Journal of the Texas Supreme Court Historical Society (Summer 2020), pg. 14 ↩︎

- Bollaert, “Personal Narrative, 1840-1844,” pg. 191. ↩︎

- Ken Wise, “District of Brazos: The Republic’s Secret Court,” Journal of the Texas Supreme Court Historical Society (Summer 2020), pg. 10-11. ↩︎

- Hogan, pg. 256–57. ↩︎

- Constitution of the Republic of Texas Article IV, § 10 ↩︎

- Constitution of the Republic of Texas, Article IV, §4 ↩︎

- Ken Wise, “District of Brazos: The Republic’s Secret Court,” Journal of the Texas Supreme Court Historical Society (Summer 2020), pg. 16. ↩︎

📚 Curated Texas History Books

Dive deeper into this topic with these handpicked titles:

- Lone Star Law: A Legal History of Texas

- The Texas Republic: A Social and Economic History

- The Constitution and Laws of the Republic of Texas

- Laws and Decrees of the State of Coahuila and Texas, in Spanish and English

- History of the American Frontier – 1763-1893

- Mexican Law for the American Lawyer

Texapedia earns a commission from qualifying purchases. Earnings are used to support the ongoing work of maintaining and growing this encyclopedia.