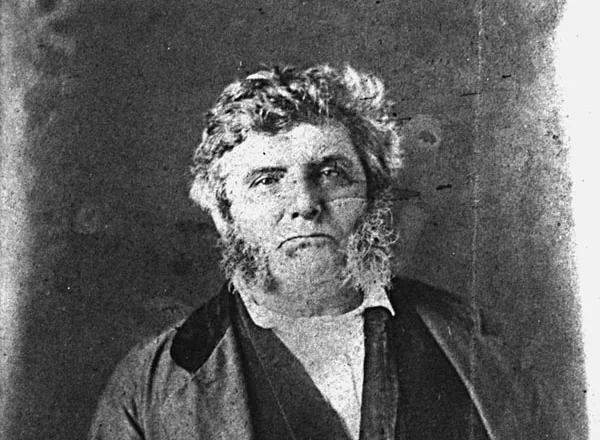

David Gouverneur Burnet (1788–1870) was a lawyer, empresario, and politician who served as the first interim president of the Republic of Texas in 1836. His life was marked by bold ventures, political disappointments, and a stubborn commitment to principle that made him both respected and divisive.

Born into a prominent New Jersey family and drawn into a revolutionary expedition in South America as a young man, Burnet carried an entrepreneurial and adventurous spirit into Texas, where he became a central but often controversial figure in the struggle for independence and the formation of republican government.

Early Life and Revolutionary Ventures

Burnet was born on April 14, 1788, in Newark, New Jersey, the fourteenth child of Dr. William Burnet, a Revolutionary War physician and Continental Congress delegate, and his second wife, Gertrude Gouverneur Rutgers. Orphaned young, David was raised by older brothers, most notably Jacob Burnet, a lawyer and later U.S. senator from Ohio, and Isaac Burnet, who became mayor of Cincinnati. Their stature and achievements loomed over David’s life, sharpening his ambition and deepening his frustration at his own frequent reversals.

Restless, he pursued opportunities far beyond home. In 1806 he sailed with General Francisco de Miranda’s expedition to liberate Venezuela from Spanish rule. The filibuster was quickly defeated, and Burnet returned to New York disillusioned. His involvement in the Venezuela campaign, though brief, marked him as part of the wider Atlantic revolutionary ferment that linked struggles from South America to North America.

In the following decade Burnet drifted through ventures in Louisiana and Texas. He attempted trading with the Comanche near the Brazos headwaters around 1817, living for some time in frontier conditions and battling ill health. He recovered, returned to Ohio, and studied law in his brother Jacob’s office, but financial security eluded him.

Empresario and Early Texas Years

Burnet reentered Texas in the 1820s as one of many Anglos seeking opportunity under Mexico’s colonization laws. In 1826 he secured an empresario contract to settle 300 families north of the Old San Antonio Road, but the endeavor floundered. By 1830 he sold his rights to the Galveston Bay and Texas Land Company, receiving cash and certificates that never brought lasting benefit.

That same year he married Hannah Este of Morristown, New Jersey. The couple moved permanently to Texas in 1831, bringing with them a steam engine to power a sawmill. They built their home, Oakland, on the San Jacinto River. Burnet operated the mill with mixed success; disputes with Mexican authorities over his refusal to convert to Catholicism and persistent financial losses forced him to sell it by 1835. A lifelong Presbyterian, he organized early Protestant services and Sunday schools in Texas and maintained a strict personal piety that shaped both his private life and political reputation.

Despite financial setbacks, Burnet earned a reputation for articulate speeches and principled positions. At the Convention of 1833 he represented Liberty, co-drafted petitions for separate statehood within Mexico, and spoke against the African slave trade. Though not yet a prominent leader, he was respected for his education and seriousness of purpose.

From Reluctant Delegate to Interim President

Burnet’s politics in the mid-1830s were cautious. He disliked Santa Anna’s centralizing dictatorship but opposed hasty independence, preferring restoration of Mexico’s 1824 federalist constitution. For this reason, he was not elected a delegate to the Consultation of 1835 or initially to the Convention of 1836.

Nevertheless, he was present at Washington-on-the-Brazos as the convention deliberated independence. Accounts suggest he had come partly on private business but stayed on as events unfolded. After the declaration of independence, the delegates — reluctant to elevate one of their own and with leading figures such as Austin and Houston absent — turned to Burnet as a compromise candidate. On March 17, 1836, he was elected interim president by a close vote. Lorenzo de Zavala was chosen vice president.

Burnet’s sudden elevation reflected both his availability and his image as a man of learning and principle, though not a polarizing firebrand. Yet it also meant he assumed office with a weak base of political support just as Texas faced its gravest crisis.

Crisis Presidency of 1836

Burnet took office amid calamity. The Alamo had fallen; civilians were fleeing in the Runaway Scrape. Burnet ordered the government to move from Washington-on-the-Brazos to Harrisburg, closer to Galveston and the U.S. border, to preserve communication and security.

He declared martial law, ordered military enrollment, and threatened land forfeiture for those who abandoned Texas. These measures provoked resentment even as they reflected the desperate straits of the republic.

Burnet’s most famous clash came with General Sam Houston, who retreated eastward to regroup. Burnet accused Houston of cowardice; Houston in turn dismissed Burnet as meddling and ineffectual. Their rivalry became one of the defining features of early Texas politics.

After Houston’s victory at San Jacinto, Burnet personally negotiated the Treaties of Velasco with the captured Santa Anna. By the public treaty, Mexico promised to cease hostilities; in a secret agreement, Santa Anna pledged to press for recognition of Texas independence. Burnet’s decision to spare Santa Anna enraged many Texans, who demanded execution. Some even called for Burnet’s arrest, a measure of his unpopularity despite his central role in securing peace.

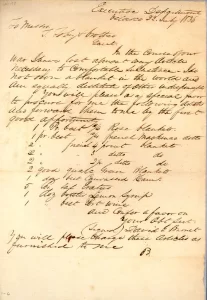

During this time, Burnet struggled financially. Writing from Velasco in July 1836, he asked New Orleans businessmen Thomas and Samuel Toby to “confer a favor” on him:

“In the course of our War I have lost almost every Article necessary to Comfortable Subsistence. I do not own a blanket in the world and am equally destitute of other indispensables.”

Burnet asked them to send him ten blankets, a dozen canvassed hams, baking soda, a dozen bottles of lemon syrup, and a bottle of Port wine. Toby and Brother Company, led by two New Orleans businessmen, had recently been made the purchasing agent of the Republic of Texas in New Orleans. The letter (right) sheds light on the domestic life of one of Texas’ leading statesmen at a time of turmoil in the young republic.

When Houston took office as elected president in October 1836, Burnet left embittered and politically weakened, convinced his neighbors had turned against him.

Vice President and Rivalry with Houston

In 1838 Burnet rode Mirabeau B. Lamar’s popularity to the vice presidency. He sometimes acted as secretary of state and even as acting president during Lamar’s absences. He supported Lamar’s expansive policies, including the campaign against the Cherokee that culminated in the Battle of Neches, in which Burnet personally fought and was lightly wounded.

Yet Burnet never escaped Houston’s shadow. The two men traded insults, challenges, and pamphlets, each accusing the other of dishonesty or cowardice. Their enmity dominated political discourse. In the bitter presidential election of 1841, Houston defeated Burnet decisively, cementing Houston’s dominance.

Later Career and Decline

After annexation in 1845, Burnet served briefly as Texas’s first secretary of state under Governor J.P. Henderson. He also sought federal judgeships and other appointments but failed, despite his brothers’ influence in Whig politics.

Tragedy marked his later years. His wife Hannah died in 1858, leaving him bereft. Their only surviving child, William, entered the Confederate Army and was killed in battle at Spanish Fort, Alabama, in 1865. Burnet, once surrounded by a large family, was left the last survivor of his household.

Financially insecure, he rented out his farm and lived with friends in Galveston. He continued to write, intending with Lamar to produce a history of the republic that would expose Sam Houston. In the end, disillusioned and embittered, Burnet burned his manuscript.

In 1866, he was appointed to the U.S. Senate along with Oran M. Roberts, but Reconstruction politics and the Ironclad Oath barred them from taking their seats. His final years were spent in poverty and declining health.

David Burnet died in Galveston on December 5, 1870, at the age of eighty-two. He was first buried in the Episcopal Cemetery, reinterred in Magnolia Cemetery, and later moved to Lakeview Cemetery, where the Daughters of the Republic of Texas erected a monument in 1894. Burnet County, created in 1852, was named in his honor, as were the county seat of Burnet and several schools. In 1936, during the Texas Centennial, a statue of Burnet was erected at Clarksville.

📚 Curated Texas History Books

Dive deeper into this topic with these related titles:

- Texas: A Historical Atlas

- Lone Star Nation: The Epic Story of the Battle for Texas Independence

- Texian Exodus: The Runaway Scrape and Its Enduring Legacy

Texapedia earns a commission from qualifying purchases. Earnings are used to support the ongoing work of maintaining and growing this encyclopedia.