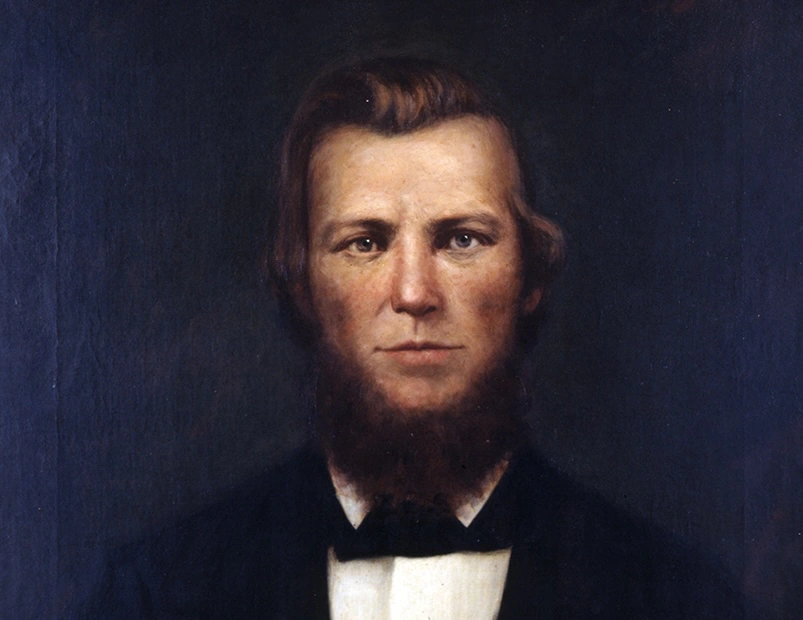

Pendleton Murrah (1826–1865) served as the tenth Governor of Texas during the final and most chaotic years of the Civil War. A lawyer, planter, and Confederate loyalist, Murrah presided over a state increasingly isolated from the rest of the Confederacy as Union forces tightened their grip on the Mississippi River and the Gulf Coast.

His brief tenure was marked by administrative strain, internal dissent, and the growing collapse of civil government. When the Confederacy fell, Murrah fled to Mexico, where he died in exile shortly thereafter. Though Murrah is largely forgotten, his governorship reflected the fragmentation and desperation of the Confederate cause in its final stage.

Early Life and Entry into Politics

Murrah was born in South Carolina in 1826 and raised in an orphanage in Alabama. He attended the University of Alabama and studied law, eventually establishing a successful legal. However, Murrah from tuberculosis moved to Texas seeking the relief of a dry climate. He settled in the eastern town of Marshall in Harrison County—a center of slaveholding wealth and secessionist sentiment—and married the daughter of a wealthy planter.

Murrah practiced law and became involved in Democratic politics. He won election to the Texas House of Representatives in 1857. He was not a particularly prominent or charismatic legislator, but his background in law and his staunch Southern views made him a natural candidate for higher office as Texas aligned itself more fully with the Confederate cause. Despite suffering from chronic tuberculosis, Murrah remained politically active and supported the Confederacy’s war effort.

Governorship During Wartime Collapse

In 1863, Murrah was elected governor of Texas, succeeding Francis R. Lubbock, who left office to take a post in Jefferson Davis’s Confederate administration. Murrah inherited a state under immense strain. By this point, the Union controlled most of the Mississippi River and much of the Louisiana border, isolating Texas from the rest of the Confederacy. Though Texas was relatively free from direct invasion, it faced increasing pressure to provide men, supplies, and logistical support to the larger Confederate war effort.

Murrah’s administration struggled to balance state sovereignty with Confederate demands. He frequently clashed with military authorities, particularly Confederate conscription agents, over the enlistment of state militia and enforcement of military orders. He resisted efforts to strip Texas of men and resources, insisting that the state had the right to retain troops for internal defense and Native American frontier protection.

Even as Confederate leaders pleaded for reinforcements during the Union Red River Campaign in Louisiana in 1864, Murrah blocked the deployment of Texas state troops beyond the Sabine. Many Texans were already serving in the Confederate States Army, but Texas also had militia and frontier troops that Murrah believed should not come under Confederate control. Historian T.R. Fehrenbach explained, “The Confederacy was structured with strong powers reserved to the states, and Murrah intended that these should not be usurped, war or not.” 1

His position was based not only on constitutional principles but also reflected practical concerns over Comanche and Kiowa attacks ongoing at the time. The question of frontier defense much concerned the Tenth Legislature, which convened as Murrah took office in early November 1863. The legislature enacted the Frontier Defense Act on December 15, 1863, which exempted all men serving in western local defense units from regular conscription.

Confederate military law conflicted with this new state law, since it allowed the Confederacy to call on state units, just as U.S. law allowed the president to federalize National Guard troops (state militia) in wartime. Murrah refused to acknowledge the supremacy of the Confederate law. Fehrenbach wrote,2

“This was a classic case of state–federal juxtaposition; Texas interposed its own military laws between its citizens and Confederate law. Murrah defended the Texas position stubbornly. His case was simple: Richmond could not require Texas to enforce laws at variance with its own needs or the desires of its own citizens. Murrah was a strict constitutionalist and never wavered. He caused vast annoyance in Richmond, where [President] Davis, beset with problems, had no brief for constitutional niceties.”

Meanwhile, Murrah faced dissent within Texas itself. Resistance to Confederate conscription, desertion, and anti-government sentiment rose dramatically in the war’s final years. Unionist communities in the Hill Country and North Texas—many composed of German immigrants and small farmers—openly defied Confederate authority. Murrah’s government resorted to harsh crackdowns and tolerated extralegal violence in some areas, including the use of vigilante groups to suppress suspected Union sympathizers.

While he tried to maintain order and supply Confederate armies, Murrah lacked the political tools and military strength to reverse the larger tide of defeat. He operated within a disintegrating administrative structure, marked by shortages of food, arms, paper, and personnel. His health deteriorated steadily throughout his term, limiting his effectiveness and visibility in Austin.

Flight to Mexico and Death in Exile

As Union victory became inevitable in early 1865, Murrah—like several other high-ranking Confederate officials—chose exile over surrender. In June 1865, just weeks after the formal collapse of the Confederate government, he crossed into Mexico along with other members of the Texas civil administration. They hoped to regroup or at least avoid imprisonment by federal authorities.

Murrah’s health, long fragile, declined rapidly in the harsh conditions of northern Mexico. He died in Monterrey on August 4, 1865, at the age of 39, likely from tuberculosis compounded by exhaustion and exposure. He was buried in Mexico.

Legacy and Historical Assessment

Pendleton Murrah is among the least known of Texas’s nineteenth-century governors. His short and beleaguered administration occurred during a period of near-total collapse—militarily, economically, and administratively. He was not a major figure in Confederate leadership and lacked the political capital to influence strategy or policy beyond Texas. His time in office is remembered less for specific accomplishments than for the general condition of the state under his leadership: isolated, fractious, and facing inevitable defeat.

Nonetheless, Murrah’s governorship reveals important features of wartime governance in the Confederacy’s periphery. Unlike governors in the upper South, Murrah faced relatively little direct Union occupation, except along the coast, but dealt with anarchy, frontier violence, and significant internal dissent. His resistance to conscription and defense of state militia control echoed the larger debate between states’ rights and centralized Confederate authority that ultimately weakened the Southern war effort.

Murrah’s death went largely unremarked in postwar Texas, as political attention shifted to the question of Reconstruction and reentry into the Union. Unlike Sam Houston or Governor Lubbock, who authored a popular memoir, Murrah left behind no significant personal papers, memoirs, or enduring political legacy.