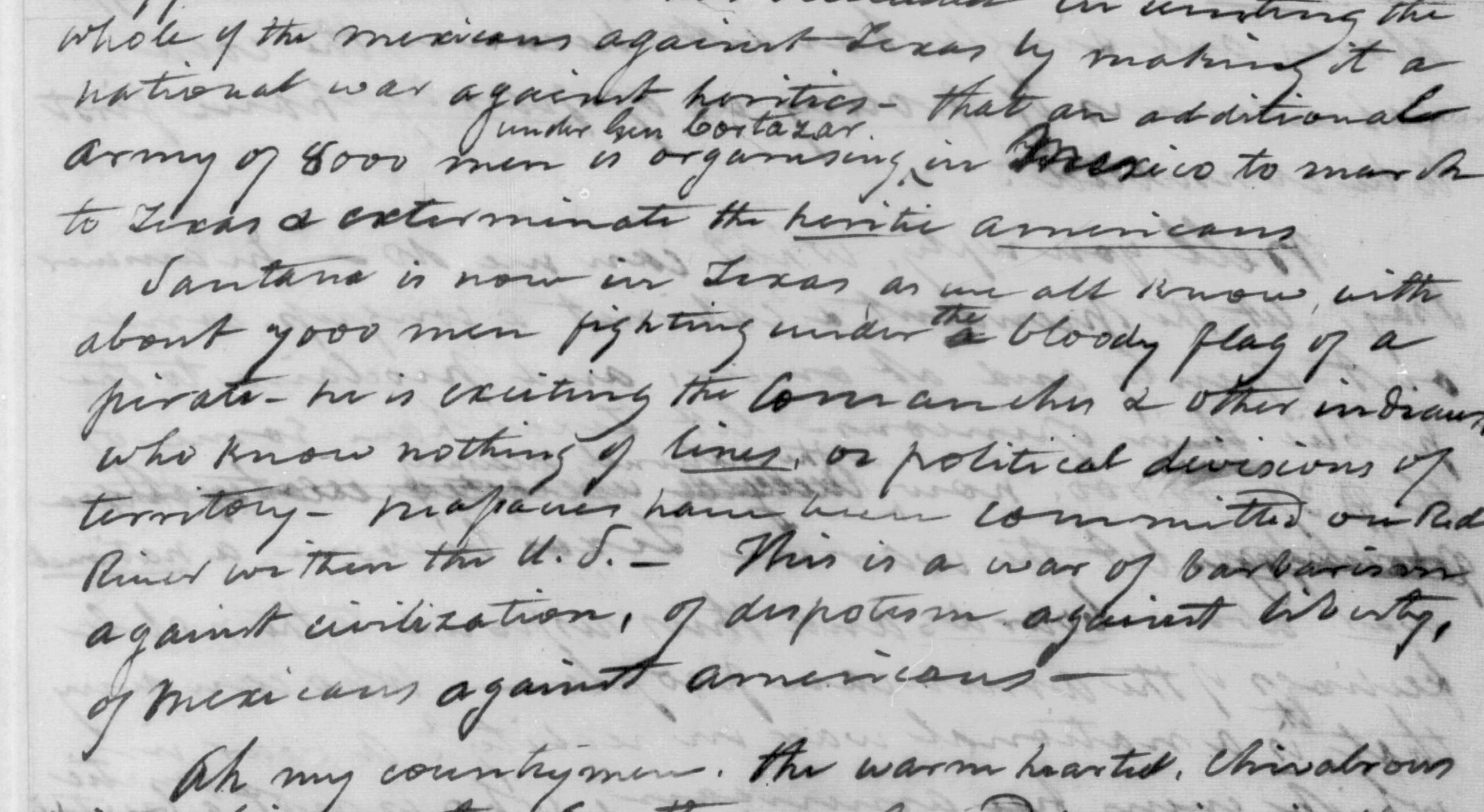

Stephen F. Austin, the “Father of Texas,” wrote an impassioned letter to the President to the United States, Andrew Jackson, at the height of the Texas Revolution, appealing for financial and military aid. The letter documents the high drama and desperation of the separatist cause during the Mexican Army’s 1836 invasion of Texas.

Though Jackson declined to intervene—the Texans eventually won their independence without official U.S. assistance—he later arranged to diplomatically recognize Texas, a key step toward legitimizing and stabilizing the fragile new republic.

This article includes the full text of Austin’s letter, scans of the original, and historical context.

Related Content

- The Life of Stephen F. Austin

- The Texas Revolution (1835-1836): Causes, Battles, and Aftermath

- Constitution of the Republic of Texas (1836)

- Texas Declaration of Independence (1836)

- The Collapse of Mexican Federalism and the Road to Texas Independence

- Santa Anna: The Villain of the Texas Revolution

This article is part of Texapedia’s curated primary source collection, which makes accessible both famous and forgotten historical records. Each source is presented with historical context and manuscript information. This collection is freely available for classroom use, research, and general public interest.