George W. Bush served as Governor of Texas from 1995 to 2000, a period that now seems unusually cooperative in the state’s political history. Though remembered nationally for his presidency, Bush’s years in Austin showcased a political style that blended conservative priorities with bipartisan rapport—a tone increasingly rare in modern Texas politics.

Bush governed during a transitional moment: Texas was shifting decisively Republican, yet its institutions still relied on cross-party alliances. At the same time, national politics were becoming increasingly partisan, marked by the 1994 Republican Revolution and the impeachment of President Bill Clinton. In this context, Bush stood out for his affable style and legislative pragmatism, building coalitions with Democrats and Republicans alike. This contributed to his national appeal in the 2000 presidential election.

A New Republican in a Changing Texas

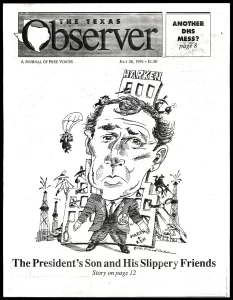

Bush entered the 1994 governor’s race as the son of a former president and a relative unknown in Texas politics. His opponent, incumbent Democrat Ann Richards, was widely admired for her wit and charisma, but her policies were unpopular with conservatives.

Bush ran a disciplined campaign focused on four core issues: education reform, juvenile justice, tort reform, and welfare restructuring. His message emphasized personal responsibility, local control, and what he termed “compassionate conservatism.”

The victory stunned the political establishment. Bush won 53.5% of the vote to Richards’ 45.9%, becoming only the second Republican elected governor of Texas since Reconstruction. His success marked a turning point in Texas political history: the end of Democratic dominance and the rise of a new, ideologically conservative Republican era.

Governing with Democrats: The Bullock-Laney-Bush Triangle

Despite his party’s ascendancy, Bush governed with a divided state government. The Lieutenant Governor, Bob Bullock, was a Democrat, as was Speaker of the House, Pete Laney. Both were powerful figures in the legislative process, and their cooperation was essential to Bush’s success.

Bush understood this dynamic and chose cooperation over confrontation. He met regularly with Bullock and Laney, developed personal relationships with them, and deferred to their institutional expertise when needed. Bullock, a powerful figure in Texas politics at the time, even endorsed Bush for reelection in 1998 and reportedly told confidants that Bush would make a good president. Laney also maintained a cordial relationship with the governor, helping facilitate bipartisan legislation.

Bush also developed good relationships with many less powerful members of the legislature. He often watched legislative proceedings on a television from the Governor’s Mansion and would reach out to members to congratulate them on an effective speech or ask questions about a bill. Sometimes he visited legislators and their staff at the Capitol and he hosted breakfast meetings at the Governor’s Mansion with small groups of legislators.1

In legislative election years, Bush declined campaign against incumbents, even Democrats.

Bush’s ability to maintain alliances in the legislature reflected both his temperament and the constraints of the office. The Texas governorship is constitutionally weak, with limited appointment powers and little control over the budget. Success depends less on unilateral action and more on coalition-building, persuasion, cultivating public opinion.

The Shadow and Support of George H.W. Bush

No account of George W. Bush’s rise can ignore the influence of his father, former President George H.W. Bush. A veteran of World War II, George H.W. Bush built one of the most extensive resumes in modern American politics. He served as a congressman from Texas, U.S. ambassador to the United Nations, chairman of the Republican National Committee, U.S. envoy to China, and Director of Central Intelligence. He was elected Vice President under Ronald Reagan and ultimately served as the 41st President of the United States from 1989 to 1993.

The elder Bush was also a familiar and respected figure in Texas, having made Houston his political and personal home since the 1960s. His deep donor network, ties to the oil industry, and national stature helped bolster George W. Bush’s early credibility. Many of the younger Bush’s earliest political supporters and advisers had longstanding connections to his father’s campaigns and White House. While George W. Bush was careful to craft his own identity—framing himself as a Texan first and Washington outsider—his father’s legacy was always present.

Observers have pointed to differences in the personalities and priorities of the two men. Despite this, the elder Bush remained a valued counselor during his son’s governorship.

The Team Behind the Governor

Although Bush was the public face of his administration, his effectiveness as governor owed much to a skilled and tightly knit inner circle—some of whom had served his father or emerged from the same political orbit. At the center was Karl Rove, a seasoned strategist who had worked on campaigns dating back to the 1970s and advised both George H.W. Bush and other Texas Republicans. Rove became the architect of George W. Bush’s messaging and electoral strategy, crafting the “compassionate conservative” label that helped him appeal beyond the Republican base.

Joe Allbaugh, Bush’s gubernatorial chief of staff, was known for his no-nonsense management style and political discipline. He had ties to national GOP operatives and would later lead the Federal Emergency Management Agency under President Bush. Karen Hughes, communications director and one of Bush’s most trusted aides, worked closely with the press and played a key role in shaping Bush’s public persona. She was central not just to media relations but to speechwriting and internal messaging.

On policy, Margaret Spellings—then known as Margaret La Montagne—was Bush’s point person for education reform and helped develop the accountability measures that would later influence national legislation. Alberto Gonzales, Bush’s legal counsel, managed judicial appointments and clemency decisions, including high-profile death penalty cases. Bush later appointed Gonzales to the Texas Supreme Court and, during his presidency, made him U.S. Attorney General.

Other influential figures included Harriet Miers, who was brought in to reform the Texas Lottery Commission and would later be nominated to the U.S. Supreme Court (a nomination she eventually withdrew), and Clay Johnson, a Yale classmate who managed gubernatorial appointments and later served as Deputy Director of the Office of Management and Budget. Don Evans, a longtime friend and business ally from the Midland oil world, served as a key fundraiser and would later become U.S. Secretary of Commerce.

Together, these advisers formed a close, loyal team that emphasized discipline, loyalty, and message control. Many had experience in George H.W. Bush’s political world, but were now helping to craft a more modern, assertive brand of Republican leadership that defined George W. Bush’s rise. Their shared experience and cohesion allowed the governor’s office to run with remarkable focus and efficiency.

Leadership Style

Though he relied on a team of close advisors, Bush was known to make his own decisions, and developed reputation for decisiveness, in contrast to his Republican predecessor, Bill Clements, who often waffled over veto decisions and other matters. Terral Smith, Bush’s legislative director, recalled boardroom style meetings where veto decisions were made. Typically present in the room were advisors Smith, Vance McMahan, Karen Hughes; Albert Hawkins, Alberto Gonzales, and, at times, Karl Rove. Smith said in an interview years later:2

“The governor would sit at the head of the table and listen to both sides of the veto argument. He’d ask questions, and let others weigh in. We would wait until we had about ten to consider, and then we’d call the governor and say, ‘We need you to come and make some decisions.’ He would listen to both sides. And Bush would say, ‘I think I’m going to go with Terral on this; give me the bill.’ Next bill, he’d say, ‘Oh, I think I’m going to veto it. Next bill.’”

Similarly, Elton Bomer, a four-term Texas House member who served as Texas Secretary of State during Bush’s second term as governor, said in an interview,3

“Bush made decisions very quickly. No one else I’ve ever been around in a close working relationship could make a decision as firmly and as quickly as he could after hearing both sides and asking a series of questions. And after we got through with discussions, he would always go back around and ask, ‘Is there anything else that hasn’t been discussed here that we need to discuss?'”

Bush’s quick and firm decision-making later also characterized his leadership during his two terms as president. This style may have developed from observing corporate leaders during 17 years of work in the oil industry and as managing general partner of the Texas Rangers. Bush held an M.B.A. degree from Harvard Business School and had served for about five years in the Texas Air National Guard. Being the son of a very powerful man also likely contributed to his leadership style.

Critics sometimes said that Bush’s decisiveness reflected laziness, a lack of intellectual curiosity, and a dependence on impulsive and quick-formed prejudices. In contrast to Bush, Bush’s presidential successor, Barack Obama, often took longer to weigh decisions, went against his advisors less often, and sometimes changed his mind after reaching decisions.

Bush himself shed light on his own decision-making process in a 2010 autobiography, Decision Points, which describes various hard decisions that he faced during his lifetime.

School Choice and Testing

Bush made education reform the centerpiece of his administration. Drawing on a growing national consensus around standards-based accountability, he pushed for a system that measured school performance through standardized testing and tied funding and administrative consequences to those results.

Under his leadership, Texas implemented the Texas Assessment of Academic Skills (TAAS) as a key performance metric. The state began rating schools and districts based on student outcomes, with particular attention to minority and economically disadvantaged students. Teachers and administrators were rewarded or penalized based on these scores.

Bush also signed legislation expanding charter schools and reducing state regulations on local school districts, aiming to empower communities while holding them accountable. His rhetoric centered on eliminating excuses: if schools had more control, they also had more responsibility.

The reforms did not go unchallenged. Many Democrats and teacher organizations warned that an overemphasis on testing would narrow curricula and encourage “teaching to the test.” Efforts to promote school vouchers also met bipartisan resistance, especially from rural Republicans and Democrats who feared harm to public schools. Bush ultimately scaled back his voucher proposals in the face of legislative opposition.

Juvenile Justice, Crime Policy, and Capital Punishment

Bush also prioritized reforming Texas’s juvenile justice system amid growing public concern over youth crime. He signed legislation lowering the age at which juveniles could be tried as adults to 14 for certain violent offenses, and expanded sentencing options for serious juvenile crimes.

In adult criminal justice, Bush supported a tough-on-crime approach. Texas carried out 152 executions during his governorship, far more than any other state in that period. One execution in particular—that of Karla Faye Tucker in 1998—drew international attention. Bush declined to grant clemency despite emotional appeals, and his dismissive comments in a later interview stirred controversy.

While popular with many voters, Bush’s criminal justice record drew criticism from civil rights groups and some Democratic lawmakers. A major legislative flashpoint came in 1999, when a hate crimes bill—introduced after the murder of James Byrd Jr.—was blocked in the legislature. Bush declined to endorse it, saying “all crimes are hate crimes.” The decision infuriated civil rights advocates and revealed ideological rifts within the state.

Faith-Based Welfare Initiatives

Bush also pursued reforms to the delivery of social services, particularly through partnerships with faith-based organizations. His administration launched initiatives to allow churches and religious nonprofits to offer services with reduced regulatory oversight. The premise was that such groups could more effectively reach the poor and marginalized.

This initiative included pilot programs where faith-based drug rehabilitation centers and group homes could receive state funds without being subject to standard licensing requirements. Supporters saw it as an innovative way to leverage community networks. Critics, however, raised concerns about accountability and transparency, especially after reports surfaced of abuse and mismanagement at some facilities.

The legislation ultimately passed in modified form after a contentious debate in the legislature. Bush defended the program as a moral mission, emphasizing that faith-based groups could change lives in ways government could not. The concept foreshadowed the Office of Faith-Based Initiatives that he would later create as president.

Tort Reform and the Business Climate

Bush worked closely with the business community to advance tort reform, seeking to reduce what many perceived as lawsuit abuse. He signed laws capping punitive damages, raising standards for proving gross negligence, and limiting venue-shopping by plaintiffs.

These reforms were welcomed by corporations, insurance companies, and professional groups like physicians, who had long complained about the cost and unpredictability of litigation. The changes improved Texas’s reputation among business leaders and contributed to its growing economy.

Bush’s opponents, however, charged that these reforms limited the rights of ordinary Texans to seek justice and protected negligent corporations. The legislation passed over objections from trial lawyers and some Democrats, illustrating the ideological leanings of the new Republican coalition.

Less remarked upon, but noteworthy, was Bush’s support for expanding wind energy. Although not a central priority, Texas became a national leader in wind generation during his tenure. This development was driven more by market forces and federal incentives than by gubernatorial initiative, but Bush was not an obstacle—and occasionally touted the achievement.

The 1998 Landslide and Presidential Momentum

Bush’s approach to governing paid political dividends. In 1998, he won reelection in a landslide, defeating Democrat Garry Mauro with 68.6% of the vote—a record for a Texas gubernatorial race. He carried every major demographic group and nearly every county, a sign of his broad popularity.

This overwhelming victory immediately positioned Bush as a national figure. Political commentators began speculating about a presidential run, and his advisers quietly began laying the groundwork. By late 1999, Bush had formally entered the race for the Republican nomination, touting his record in Texas as evidence that he could “bring people together to get things done.”

Private Life and Public Image

Bush’s private life during the governorship reinforced his political brand. He had quit drinking in 1986 and was an outspoken born-again Christian. He often credited his faith with giving him clarity and discipline. These elements were not just background traits—they featured prominently in his public messaging.

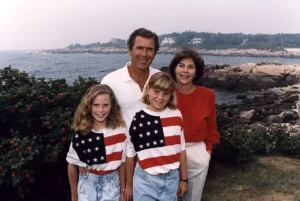

His family also projected stability. Laura Bush, a former librarian, was active in promoting literacy and education. Their twin daughters, Barbara and Jenna, were students during much of Bush’s tenure. Stories about the Bushes were generally positive, reinforcing the image of a grounded, disciplined leader.

In 1998, Bush sold his stake in the Texas Rangers baseball team, earning a reported $15 million on an initial $600,000 investment. The sale ended any lingering questions about financial entanglements and added to his aura of success.

Despite scrutiny of past behavior—including questions about a decades-old DUI and rumors of drug use—Bush largely defused controversies by framing them as part of a youthful chapter he had long since left behind. His narrative of personal growth resonated with many voters.

A Legacy Repudiated

In hindsight, Bush’s governorship occupies an unusual space in Texas political memory. He was an effective conservative leader who prioritized cooperation and respect. Yet in the decades since, the Texas GOP has undergone a dramatic transformation.

Today’s Republican leadership in Texas—exemplified by figures like Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick and Attorney General Ken Paxton—frequently embraces a more combative, populist, and nationalist tone. The party’s activist base often regards the Bush legacy as too moderate, too globalist, or too deferential to the establishment.

In 2021, the Texas GOP formally censured U.S. Rep. Tony Gonzales for supporting gun control legislation and same-sex marriage protections—stances that reflect the type of moderation Bush sometimes showed. George P. Bush, the former governor’s nephew, was defeated in the 2022 Republican primary for Attorney General, despite high name recognition and establishment support.

The cultural language of Bush-era conservatism—compassionate, reform-minded, institutionalist—has little currency in today’s Texas Republican politics. Instead, the party often defines itself in opposition to perceived elite consensus, global institutions, and bipartisan compromise. The rise of Donald Trump accelerated this shift, but the realignment had been brewing for years.

Bush himself has remained largely silent on Texas politics, aside from occasional comments defending democratic norms and criticizing political extremism. His reputation remains relatively strong among moderates and independents, but his name no longer carries the weight it once did among GOP primary voters.

Sources Cited

- Brian McCall, The Power of the Texas Governor: Connally to Bush (Austin, TX, University of Texas Press, 2010), 101. ↩︎

- Interview with Terral Smith, quoted in McCall, The Power of the Texas Governor, 103. ↩︎

- Interview with Elton Bomer, quoted in McCall, The Power of the Texas Governor, 104 ↩︎

📚 Curated Texas History Books

Dive deeper into this topic with these handpicked titles:

- Front Row Seat: A Photographic Portrait of the Presidency of George W. Bush

- Portraits of Courage: A Tribute to America’s Warriors (by George W. Bush)

- Out of Many, One: Portraits of America’s Immigrants (by George W. Bush)

- 43: Inside the George W. Bush Presidency

- The Last Republicans: Inside the Extraordinary Relationship Between George H.W. Bush and George W. Bush

- Rick Perry: A Political Life (Clifton and Shirley Caldwell Texas Heritage)

Texapedia earns a commission from qualifying purchases. Earnings are used to support the ongoing work of maintaining and growing this encyclopedia.