Historical Context

In late 1820, American merchant Moses Austin made a bold proposal: to bring 300 families from the United States to settle in Spanish Texas. With Spain’s empire weakened and its northern frontier sparsely populated, Austin saw an opening in the colonial government’s desire to stabilize and develop the region. What began as a personal venture soon became a turning point in Texas history.

Austin had made his fortune in lead mining, first in Virginia and later in Spanish Louisiana, where he became a Spanish subject and received land grants near present-day Missouri. For years, he operated a smelting works and engaged in land speculation, but like many American businessmen, he was devastated by the economic collapse following the Panic of 1819.

Facing bankruptcy, he turned to Texas—a remote but promising frontier—with a plan to rebuild his fortunes and leave a legacy for his family. Drawing on past dealings with Spanish officials, Austin proposed to bring Anglo-American settlers who would pledge loyalty to the crown and help develop the province.

Document Summary and Significance

Austin’s initial request was rejected by Governor Antonio Martínez in San Antonio de Béxar, but with the help of Baron de Bastrop, a well-connected intermediary, Austin persuaded the authorities to reconsider. His petition was forwarded to higher officials, and the response—translated below—became the first formal approval of Anglo-American colonization in Texas.

Dated February 8, 1821, Governor Martínez’s letter set the terms: settlers had to be Catholic or agree to convert, demonstrate good character, swear loyalty to Spain, and agree to defend the territory. These requirements reflected both imperial priorities and the expectation—more aspirational than real—that foreign settlers would assimilate. The letter also reveals Spanish hopes that the newcomers would bring agriculture and industry to the region.

Before Moses Austin could act on the plan, he died in June 1821. His son, Stephen F. Austin, carried the project forward. After Mexico won independence from Spain later that year, Stephen secured confirmation of the contract in 1823, and obtained a second colonization contract in 1825, laying the legal groundwork for the Anglo-American presence in Texas.

The document below represents the origin of Anglo-American colonization in Texas—a process that began peacefully but later turned violent, as the Texas Revolution, the Mexican-American War, and recurring conflicts with Native Americans expanded the frontier and hastened U.S. settlement.

Letter from Don Antonio Martínez to Moses Austin

Under date of 17th January last past, the commandant general and superior political chief of the eastern internal provinces writes to me as follows:

‘Having thought proper to hear the most excellent provincial deputations, on the representation which your lordship [vuestra señoría], directed to me with your official letter No. 1110 of the 26th December last, I have just received its resolution, to which I have conformed; it is of the following tenor:

‘It will be very expedient to grant the permission solicited by Moses Austin, that the three hundred families which he says are desirous to do so should remove and settle in the province of Texas, but under the conditions indicated in his petition on the subject—presented to the governor of that province, and which your lordship transmitted to this department with your official letter of the 16th instant.

‘Therefore, if to the first and principal requisite of being Catholics, or agreeing to become so before entering the Spanish territory, they also add that of accrediting their good character and habits—as is offered in said petition—and take the necessary oath to be obedient in all things to the government, to take up arms in its defense against all kinds of enemies, and to be faithful to the king and to observe the political constitution of the Spanish monarchy, the most flattering hopes may be formed. The said province will receive an important augmentation in agriculture, industry, and the arts by the new emigrants who will introduce them. Which is all that this deputation has to say in reply to your lordship’s aforementioned official letter.”

‘And I transcribe it to your lordship for your information and corresponding effects, that you may cause the interested person to be informed thereof by means of a person of your confidence, who you will dispatch with an express. And you will, at the same time, send in by said express some copies of the decree, which I transmitted under date of yesterday, granting a pardon and amnesty to the Spanish refugees who are on the frontier, in order that they may be restored to the bosom of their country.

God preserve your lordship many years.

Monterey, 17th January, 1821.

Joaquín de Arredondo [signature]

To the Governor of the Province of Texas.’

All of which I transcribe to you, for your information and satisfaction, in answer to your petition. For this purpose, and in order to inform you of the deliberations of the most excellent deputation of these provinces, I have dispatched with this a person of my confidence, who is citizen Don Erasmo Seguin; and after having arranged for the removal of said families, which you have contracted with me, it will be important for you to direct that when said families come on, information shall be immediately given of the time of their arrival and the place where they have stopped in this territory.

You should then come on in company with my said commissioner, in order that we may agree as to the place or places where they may wish to establish themselves, so that I may go on there, delineate the town, and apportion out the lands agreeably to the families and the species of agriculture they intend to establish. Also, to receive from them the aforementioned oath, in order that they may from that time be considered as members united to the Spanish nation, and enter upon the enjoyment of the benefits which it extends and concedes to its citizens and to Spaniards.

I also expect from the prudence which your deportment demonstrates—and for your own prosperity and tranquility—that all the families you introduce shall be honest and industrious, in order that idleness and vice may not pervert the good and meritorious, who are worthy of Spanish esteem and of the protection of this government. That protection will be extended to them in proportion to the moral virtues displayed by each individual.

I also inform you, in order that you may communicate it to those who intend to emigrate, that the supreme Spanish government has just opened the port of the Bay of San Bernard for navigation and for introductions into this province. This measure will doubtless be very advantageous to all, and particularly to the new settlers.

God preserve you many years.

Antonio Martínez, Governor of Texas

Béxar, 8th February, 1821

To Mr. Moses Austin, of the new settlement.

In addition to the above letter, Moses Austin received two other brief communications from Governor Antonio Martínez. Written later in 1821, these letters affirmed the governor’s support for Austin’s plan and encouraged him to proceed with recruiting settlers. Martínez also authorized Austin to “administer justice” in the new colony—a task later taken up by Stephen F. Austin, who established local rules and basic judicial mechanisms.

These letters offer further insight into the early administrative framework of the settlement effort. They reflect a cooperative—if improvised—relationship between Spanish authorities and the incoming Anglo-American colonists, and suggest that Martínez and Austin had developed a foundation of mutual trust during their in-person meetings in San Antonio de Béxar in late 1820.

Letters Concerning Administration of the Colony

Antonio Martínez, Governor of Texas, to Moses Austin

Having seen your representation to this government, and finding it to be conformable with its ideas, I have to inform you that although I shall render an account of it to the supreme government, for its deliberation, still not doubting it will be approved of, you can immediately offer to the new settlers the same terms as contained in your proposals, assuring you that should the superior government make any small variation, I will in due time communicate it to you; with which I answer your aforementioned representation.

God preserve you many years.

ANTONIO MARTINEZ [undated]1

Antonio Martínez, Governor of Texas to Moses Austin

For the better regulations of the Louisiana families, who are to emigrate, and whilst the new settlement is forming, you will cause them all to understand, that until the government organizes, the authority which has to govern them and administer justice, they must be governed by, and be subordinate to you; for which purpose, I authorize you as their representative, and relying on your faithful discharge of the duty. You will inform me of whatever may occur, in order that such measures may be adopted as may be necessary.

God preserve you many years.

ANTONIO MARTINEZ.

Bexar, 24th August, 1821.

Manuscript Information

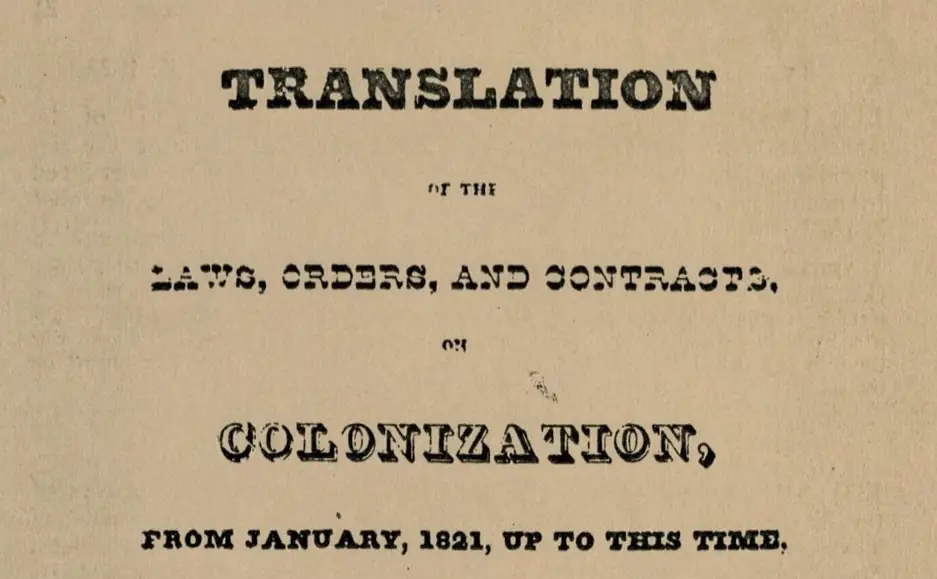

The translated communications above are drawn from a rare printed volume: Translation of the Laws, Orders and Contracts, on Colonization, From January 1821, up to 1829; In Virtue of Which, Col. Stephen F. Austin Introduced and Settled Foreign Emigrants in Texas. With an Explanatory Introduction.”

Austin himself compiled the original documents in 1829, and translated them from the Spanish with the help of his clerk, S. M. Williams. Austin’s compilation was printed by Godwin B. Cotten at San Felipe de Austin and reprinted by Borden & Moore, publisher of the Telegraph and Texas Register, in Columbia, Texas in 1837.

It is unclear if the original handwritten letters survived and, if so, where they are presently housed. Because the letters were addressed directly to Moses Austin, he likely retained the originals before passing them to his son Stephen. Spanish authorities may also have kept official copies in the provincial archives of San Antonio de Béxar or Monterrey. Some colonial-era records from Texas are held by the Archivo General de la Nación in Mexico City or the Texas General Land Office, but the specific originals of these letters may no longer exist.

In his introduction to this 1829 book, Austin wrote that the records of the colony “are now kept in a very loose and careless manner in a log cabin, exposed to all manner of casualties.” He complained that his fellow colonists had rejected a municipal tax at the ayuntamiento (council) meetings of 1828 and 1829, which could have funded the construction of public buildings for administration and better safekeeping of records.

It is likely therefore, that these foundational records were compiled and printed because Austin feared that the originals would be lost.

- Though undated, this is may be the text of the message that was delivered by the governor’s messenger, “Don Erasmo” (Erasmo Seguin), in February 1821. ↩︎

This article is part of Texapedia’s curated primary source collection, which makes accessible both famous and forgotten historical records. Each source is presented with historical context and manuscript information. This collection is freely available for classroom use, research, and general public interest.