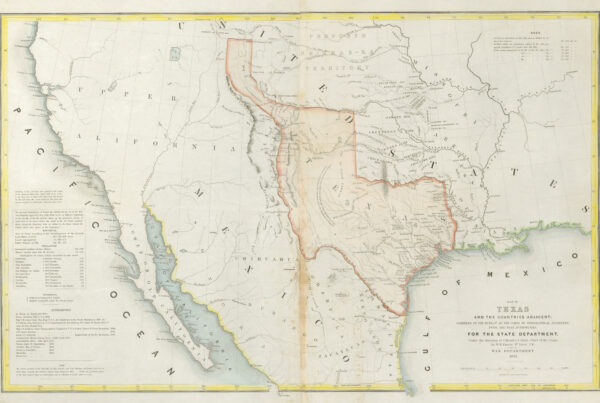

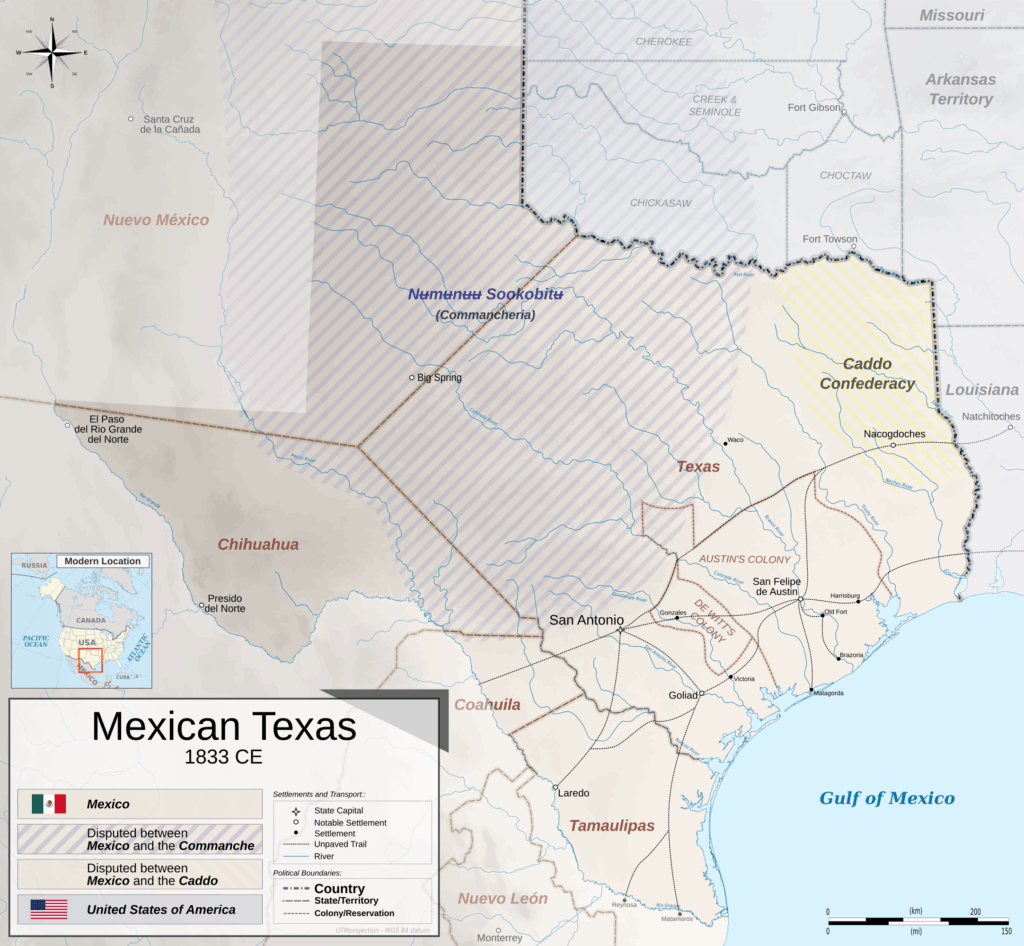

In the early 1830s, Texas was a northern frontier province of the Mexican Republic, governed as part of the larger state of Coahuila y Tejas. While Mexican law formally applied across the region, effective control was limited. Much of the territory remained in the hands of Native nations, and Anglo-American settlers in Austin’s Colony increasingly acted with autonomy.

The shaded regions show lands held by Indigenous nations whose sovereignty went largely unacknowledged by Mexican officials. The Comanche commanded the interior plains, while the Caddo Confederacy held ground in the east. Though Mexico claimed the entire territory, it lacked the capacity to enforce its authority across these zones. Forts, presidios, and colonial roads offered some cohesion, but the frontier remained volatile.

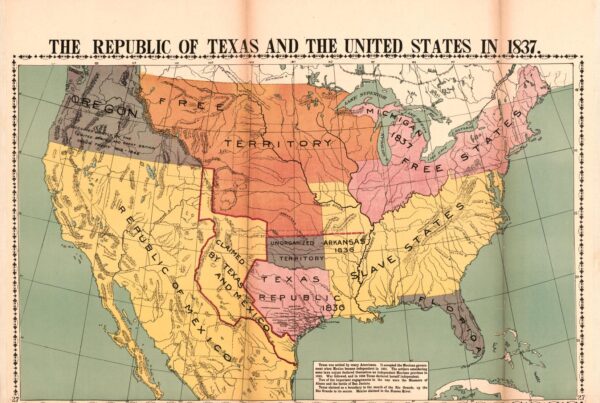

Notably, there was no formal dispute with the United States at this time. The Sabine River marked the recognized border under the 1819 Adams–Onís Treaty, and U.S.–Mexico tensions had not yet escalated. The deeper conflicts lay within: between settlers and Indigenous groups, between central authority and local independence, and between rival visions for Texas’s future. In 1833, the fault lines were already in place. Just two years later, in 1835, mostly Anglo settlers launched a full-scale revolt against Mexican authority, marking the beginning of the Texas Revolution.