On December 29, 1845, the United States formally admitted Texas into the Union as the 28th state. This act marked the culmination of nearly a decade of diplomatic maneuvering, domestic political turmoil, and international intrigue. More than a simple act of territorial expansion, the annexation of Texas was a lightning rod that inflamed sectional tensions, galvanized the ideology of Manifest Destiny, and ultimately set the stage for war with Mexico.

The Road to Independence

Originally part of New Spain, Texas had changed hands amid colonial rearrangements and wars before becoming a province of newly independent Mexico in 1821. The Mexican government, eager to populate the sparsely settled northern frontier, encouraged immigration from the United States. Anglo-American settlers poured in, many bringing enslaved laborers with them, a direct challenge to Mexico’s anti-slavery laws.

By the early 1830s, tensions flared. Settlers ignored laws requiring Catholic conversion and outlawing slavery, while Mexico imposed new restrictions to reassert authority. In 1836, after a series of clashes and the brief but bloody Texas Revolution, Texas declared itself an independent republic. Although General Santa Anna, then president of Mexico, was captured and signed a treaty recognizing Texas’s independence, the Mexican government refused to ratify it. Thus, Texas stood in diplomatic limbo: independent in fact but not in the eyes of its former sovereign.

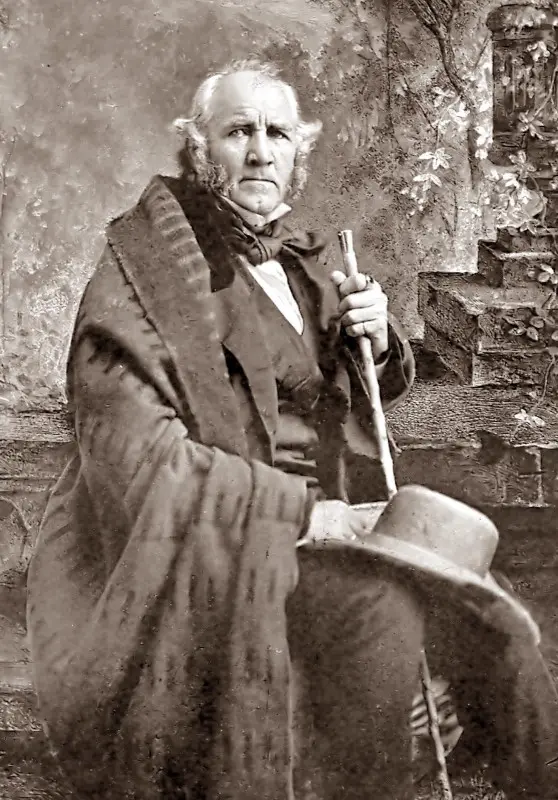

Sam Houston’s First Push for Annexation

From the outset, many Texians desired annexation by the United States, and no one championed that cause more consistently than Sam Houston. Having led Texas through its revolution and into its early years as an independent republic, Houston believed that long-term security and prosperity could only be achieved through union with the United States. His views were shaped by his deep political and personal ties to President Andrew Jackson and the broader Jacksonian tradition of national expansion.

Only a year after Texas declared independence from Mexico, the Republic made its first formal overture to the United States. In August 1837, just seventeen months after Texas declared independence and six months after the Republic’s constitution was ratified, President Houston appointed Memucan Hunt Jr. as minister to Washington. Hunt formally submitted a request for annexation to President Martin Van Buren.

Van Buren, wary of the political implications, rejected the proposal outright. He chose not to forward it to Congress for consideration, fearing it would provoke a war with Mexico, which had never recognized Texas’s independence. Additionally, Van Buren faced mounting pressure from anti-slavery factions in the North, who opposed the admission of another slaveholding territory into the Union. The proposal was seen as a threat to the delicate balance between free and slave states in Congress and risked fracturing the Democratic Party along sectional lines.

Houston was disappointed but undeterred. After stepping aside during the administration of Mirabeau Lamar—who favored continued independence—Houston returned to the presidency in 1841 and immediately revived the annexation effort. His administration would lay the groundwork for the negotiations and political momentum that would follow. The Texas question was a political landmine. Admission of a large, slaveholding territory risked upsetting the delicate balance between free and slave states.

Texas, meanwhile, struggled economically. Its vast frontier was difficult to govern, its credit poor, and its slave-based cotton economy vulnerable to global fluctuations. President Sam Houston, a pragmatic leader with deep ties to the United States, began quietly courting Britain and Mexico for recognition. British interest in seeing an independent, potentially emancipated Texas alarmed Southern leaders in the U.S., especially those who saw Texas as a buffer against British anti-slavery influence.

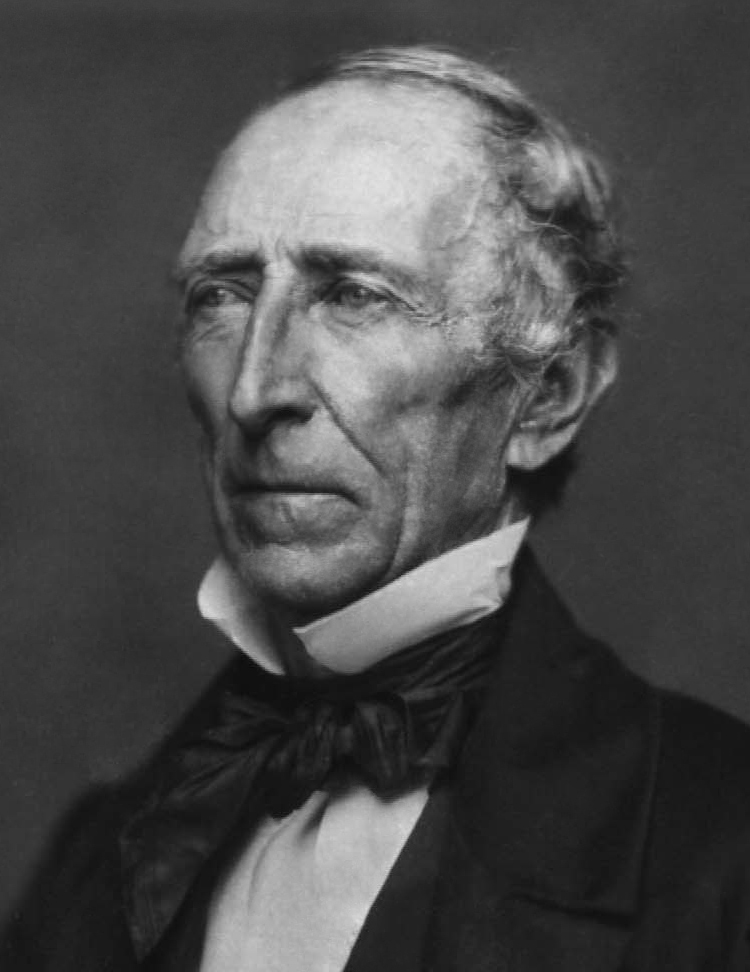

Tyler’s Gamble and Secret Diplomacy

Into this volatile mix stepped President John Tyler, a political orphan expelled from the Whig Party who saw Texas annexation as the key to political resurrection. Tyler’s administration, particularly under Secretary of State Abel P. Upshur, pursued annexation with zeal. They justified it as a national security measure to prevent British meddling in North America and protect the institution of slavery from external threat.

At the heart of these concerns was Britain’s growing interest in Texas. Although British officials had no intention of annexing Texas themselves, they were firmly opposed to Texas joining the United States. British policy aimed to keep Texas an independent republic, believing this would slow U.S. westward expansion, open new trade routes for British goods, and weaken the influence of American tariff policies.

More importantly, Britain sought to broker a peace between Mexico and Texas and had encouraged Mexico to recognize Texas’s independence—on the condition that Texas not annex itself to any other country. While British officials avoided direct pressure on slavery, American leaders suspected that Britain’s long-term goal was to steer Texas toward emancipation, thereby undermining slavery in the American South. These fears, combined with anxieties about British diplomatic influence in North America, gave Tyler and his supporters a powerful justification for urgent annexation.

A widely circulated pro-annexation pamphlet authored by Senator Robert J. Walker of Mississippi described Texas as a necessary outlet for enslaved labor and a buffer against British abolitionist influence. Walker warned that if Texas remained independent, Britain might pressure it to abolish slavery, destabilizing the institution in the American South.

By 1844, Tyler had initiated secret negotiations with Texas through his envoy, Duff Green, and Secretary of State Abel P. Upshur. These talks began in earnest after Tyler became convinced that British diplomacy posed a genuine threat to American interests in Texas. Upshur worked closely with Isaac Van Zandt, the Texas chargé d’affaires in Washington, as well as with President Sam Houston, to explore the terms of a possible treaty. The negotiations were conducted discreetly, with only a handful of officials in either government informed.

By early 1844, a draft treaty had been reached, proposing the annexation of Texas as a U.S. territory and the assumption of its public debt. But just as it was nearing completion, Secretary of State Upshur and Secretary of the Navy Thomas Gilmer died in a cannon explosion aboard a navy ship. Tyler turned to South Carolina firebrand John C. Calhoun to serve as Secretary of State and complete the annexation treaty negotiations.

Calhoun’s appointment sent an unmistakable signal: the annexation of Texas was about slavery. Soon after taking office, Calhoun authored a letter to British Minister Richard Pakenham in which he explicitly defended slavery and accused the British government of trying to influence Texas to abolish the institution. He included this letter as part of the official annexation documents submitted to the Senate, effectively making slavery a central justification for the treaty.

This alarmed anti-slavery politicians and further inflamed sectional tensions. Combined with concerns about executive overreach in treaty-making, the slavery-centric framing of the annexation effort contributed to the Senate’s overwhelming rejection of the treaty in June 1844 by a vote of 16–35.

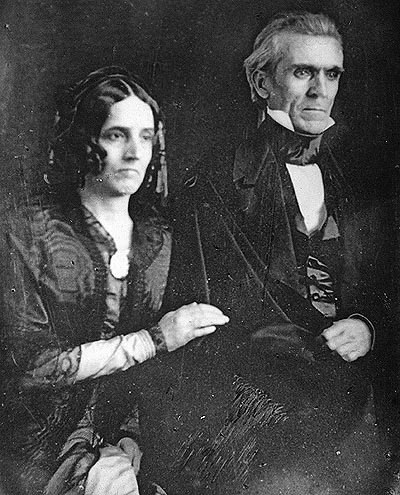

The Election of 1844: Destiny at the Ballot Box

The debate over Texas consumed the 1844 presidential election. Democrat Martin Van Buren, a cautious anti-annexationist, was denied his party’s nomination. Instead, delegates turned to James K. Polk, an ardent expansionist who campaigned on the twin promises of annexing Texas and reoccupying Oregon. Polk’s message of Manifest Destiny resonated.

But Polk’s nomination was also a triumph for Southern Democrats, who saw Texas annexation as a means of preserving their political influence and protecting slavery. The joint resolution passed by Congress allowed for up to four additional states to be carved from Texas territory, and any formed south of the Missouri Compromise line could permit slavery. This gave Southerners a powerful incentive to support annexation—and framed it as a sectional issue as much as a national one.

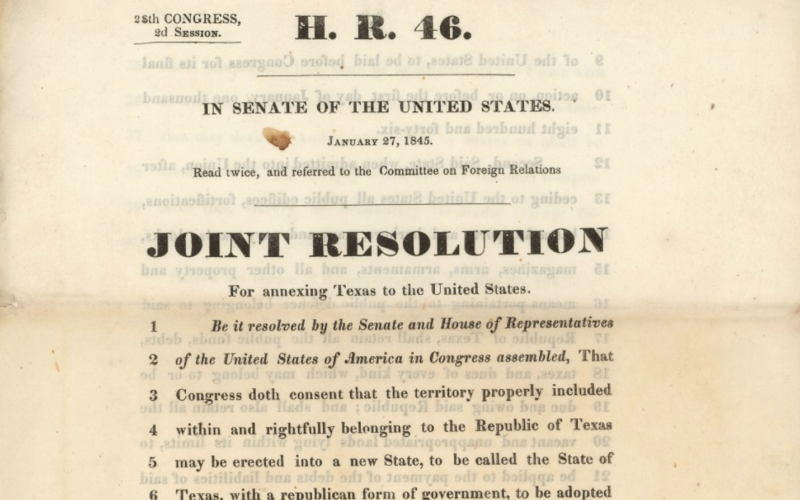

Polk narrowly defeated Whig candidate Henry Clay, who had wavered on Texas and lost Southern support as a result. Recognizing Polk’s mandate, Tyler moved quickly. With weeks left in his term, he asked Congress to bypass the treaty process and annex Texas via joint resolution—a constitutionally dubious tactic, but one requiring only a simple majority. The House, dominated by pro-annexation Democrats, approved the measure. The Senate, under intense pressure and political horse-trading, passed a compromise resolution in late February 1845.

On March 1, Tyler signed the resolution into law and sent it to Texas with an offer of immediate statehood. Polk, inaugurated just days later, allowed the process to proceed unchallenged.

Texas Chooses Union: Why Annexation Triumphed

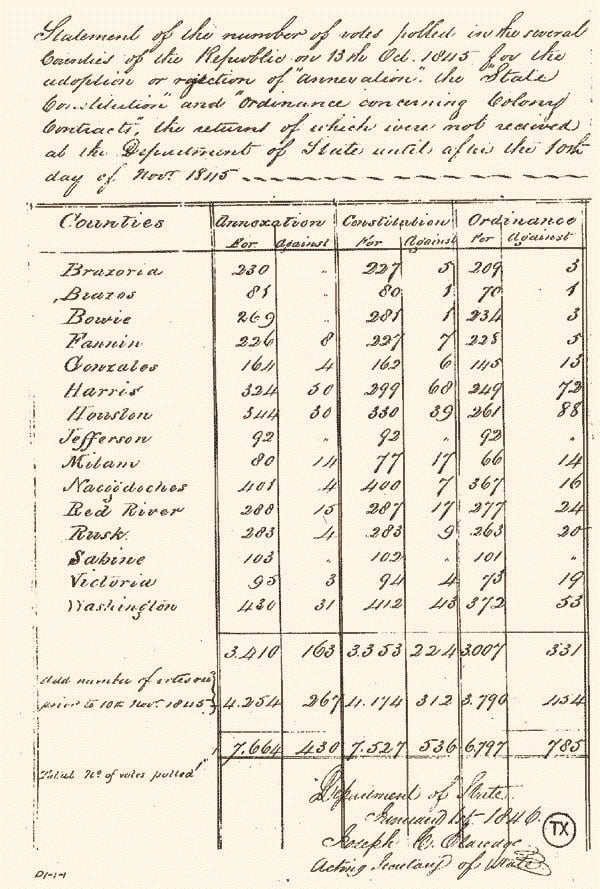

Texians enthusiastically accepted the U.S. offer. On July 4, 1845, a state convention adopted a constitution, approved by popular vote in October. On December 29, Congress admitted Texas to the Union. The Lone Star Republic ceased to exist on February 19, 1846.

The speed and enthusiasm with which Texans embraced annexation may seem surprising, given their recent hard-won independence. But the reality on the ground made annexation an appealing—if not essential—course. Despite romantic notions of frontier sovereignty, the Republic of Texas was fragile. It suffered from an overextended military, unmanageable debt, a weak currency, and diplomatic isolation. Britain and France had offered limited recognition, but could not deliver the economic or military guarantees Texas needed to survive.

Texas’s economy, dependent on cotton and slave labor, faced depressed global prices and limited markets. The republic’s tax base was too small to service its debts, and its paper currency, known as “Redbacks,” had plummeted in value. Border raids from Mexico remained a threat, and the republic lacked the military resources to repel a sustained invasion.

Annexation promised not only protection but prosperity. As part of the United States, Texas would gain access to international credit markets, a stable currency, and federal military support. It would also be integrated into a vast commercial network, enabling the export of cotton to the booming textile mills of the North and Europe. Many Anglo settlers, most of whom had immigrated from the Southern U.S., felt culturally and politically aligned with their former country and viewed continued independence as unnatural or temporary.

Nonetheless, not all Texians supported annexation. A small faction of nationalists, particularly those in President Anson Jones’s administration, favored continued independence. They believed Texas could eventually gain full international legitimacy, negotiate better trade terms, and remain free of the entanglements of American politics. Jones himself delayed calling the annexation convention, hoping to leverage competing offers from Mexico and the U.S. to secure better terms.

But the broader Texian population had little patience for delay. Many feared that rejecting or postponing the U.S. offer might cause it to evaporate—especially if domestic politics shifted again in Washington. The Texas Congress and electorate moved swiftly, leaving Jones politically sidelined. In the end, the overwhelming majority of voters approved annexation and the new state constitution. Independence, while proudly remembered, was viewed by most as a transitional chapter in a larger American story.

Mexico’s Reaction and the Road to War

The annexation enraged Mexico, which had never recognized Texas’s independence. From the Mexican perspective, the territory remained a rebellious province temporarily under foreign occupation. The decision by the United States to absorb Texas was seen as a grave insult to national sovereignty. Mexico severed diplomatic relations in protest and warned of war if the U.S. pushed further.

Though Mexico lacked the military strength to invade the United States, it could not ignore what it saw as a blatant provocation. For years, the disputed border between Texas and Mexico had remained unsettled—Texans claimed the Rio Grande as the boundary, while Mexico insisted on the older Nueces River line. In November 1845, President James K. Polk sent diplomat John Slidell to Mexico City with an offer to purchase the contested land, along with California and New Mexico. Mexican officials refused to meet with Slidell, citing domestic political instability and popular outrage.

Frustrated by the diplomatic impasse, Polk ordered General Zachary Taylor to march his troops south to the Rio Grande. When Mexican forces clashed with Taylor’s soldiers in April 1846, Polk claimed that American blood had been shed on American soil. Congress soon declared war, launching the Mexican-American War. The conflict would last two years, ultimately ending in a resounding U.S. victory and the cession of half of Mexico’s territory under the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. The annexation of Texas had lit the match.

The Legacy of Annexation

The annexation of Texas was a watershed moment in American political history. It affirmed the doctrine of Manifest Destiny—the belief that the United States was divinely ordained to expand across the continent. It demonstrated the limits of the Constitution when ambition and ideology aligned. And it irrevocably tied expansion to slavery, accelerating the sectional divide that would eventually tear the Union apart.

Texas’s admission also set a legal precedent: future annexations, such as Hawaii in 1898, would also be done by joint resolution rather than treaty. Tyler’s maneuver, though controversial, proved durable.

The story of Texas’ annexation is the story of a young nation grappling with its identity, its ambitions, and its contradictions. It is a story of diplomacy waged in secret, of politicians maneuvering for power, and ordinary settlers chasing dreams in uncertain lands.