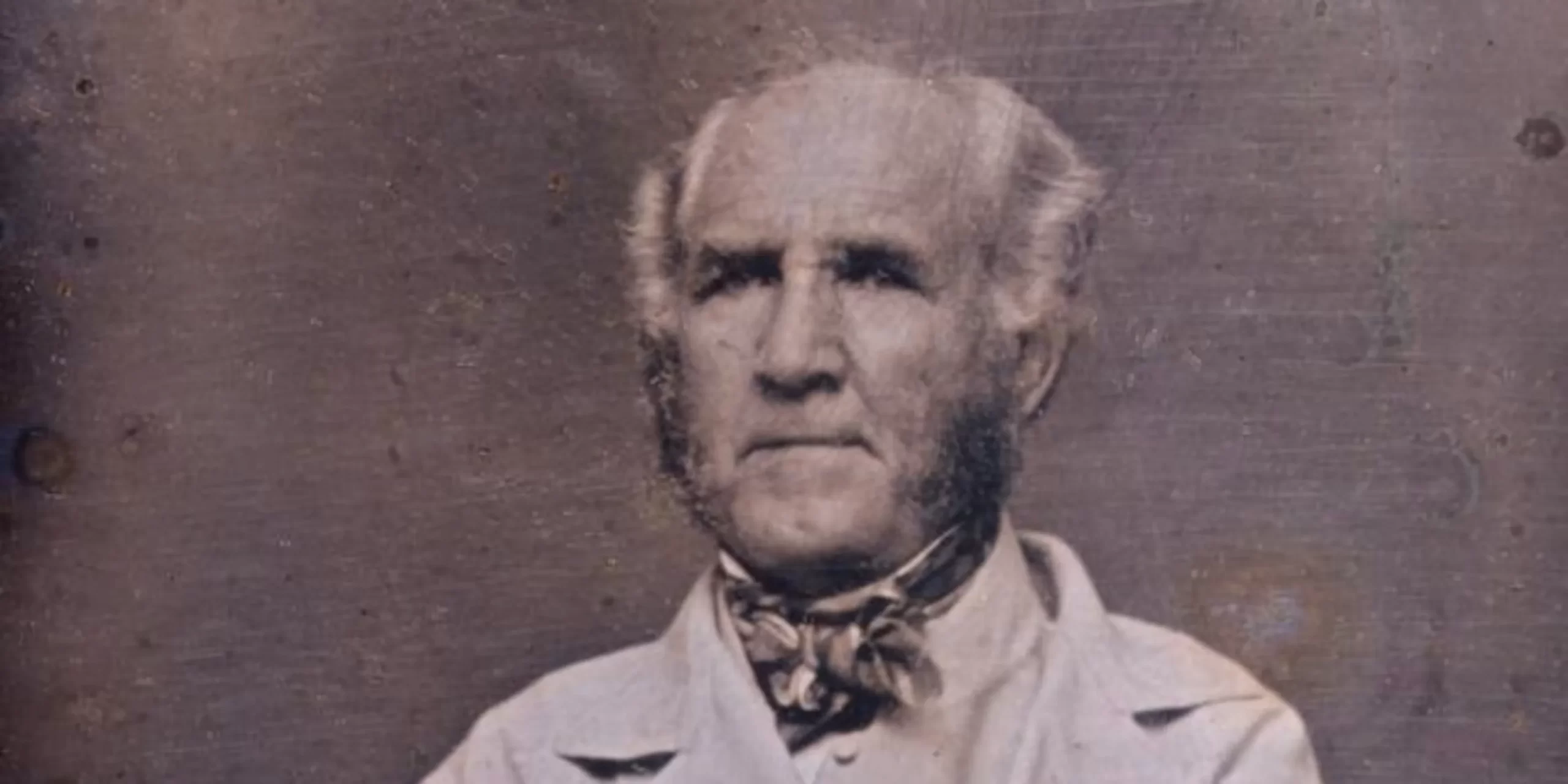

When Sam Houston took the oath of office as Governor of Texas in December 1859, he was returning to state leadership at a moment of mounting national crisis. A towering figure in Texas history, Houston had already served as commander of Texan forces during the Revolution, leading the army to victory over Santa Anna at San Jacinto in 1836. He then served as President of Texas, guided the republic through turbulent early years, and played a decisive role in securing annexation to the United States in 1845.

After annexation, Houston represented Texas in the U.S. Senate from 1846 to 1859, during which time he supported westward expansion but increasingly clashed with Southern Democrats over the spread of slavery and the rise of secessionist rhetoric. He opposed the Kansas-Nebraska Act, condemned filibustering expeditions, and resisted efforts to push the South into conflict with the North.

By the time he returned as governor in 1859, Houston stood nearly alone among prominent Texas politicians in defending the Union. In this inaugural address, he warned against sectionalism, called for investment in infrastructure and education, and advocated stronger frontier defenses—including better management of Indian relations and increased federal support. His language reflects both an enduring belief in the American constitutional system and a pragmatic concern for Texas’s internal development and border security.

When Texas voted to leave the Union in early 1861, Houston refused to swear loyalty to the Confederacy, as required under a new pro-secessionist state constitution. For this act of conscience, he was removed from office in March 1861, ending his long career in public life. This address therefore stands as Houston’s final great public appeal on behalf of Unionism, moderation, and institutional reform—a summation of his vision for Texas in the face of national disunion.

Explanatory Notes

- The Trinity, Brazos, and Colorado Rivers were central to early commerce, but their navigability was limited. Federal and state funds were often debated for internal improvements. ↩︎

- The 1845 Texas Constitution included provisions for a public education system, but progress was uneven. Houston had long championed public education in both the Republic and State periods. ↩︎

- This refers to patronage and political appointments. At the time, the spoils system dominated American politics, and integrity in appointments was a recurring public concern. ↩︎

- The public domain refers to state-controlled lands. Texas retained control of its public lands after annexation in 1845, unlike other states, and used them to fund schools and attract settlers. ↩︎

- Houston describes the vast and often undefended Texas frontier. West Texas remained sparsely populated, with frequent Comanche and Kiowa raids. Federal troops were inadequate, and Texas Rangers often filled the gap. ↩︎

- In this context, Houston is using “Confederacy” in its older, non-secessionist sense. Prior to 1861, the word was often used interchangeably with federal union or confederation to refer to the USA as a union of sovereign states. ↩︎

- At the time, federal troops were often immobile and ill-equipped to handle fast-moving Native American raids. Houston advocated for mounted troops like the Rangers who understood the terrain and tactics. ↩︎

- Annuities were payments the U.S. made to Native tribes as part of treaties. Houston is arguing that these should be routed through Texas to strengthen treaty obligations and reduce raids. ↩︎

- Houston’s call for “moral influence” likely referred to federal treaty-making and annuity diplomacy, but may also reflect the era’s belief in civilizing Native tribes through education and assimilation. As of 1859, U.S. Indian policy combined military containment with efforts to promote agriculture, Christianity, and schooling—administered by the Office of Indian Affairs. ↩︎

- Mexico experienced chronic instability after independence from Spain in 1821, with frequent coups and weak central governments. The Reform War (1857–1861), a civil conflict between liberals and conservatives, was ongoing at the time of this speech. ↩︎

- While serving in the U.S. Senate, Houston proposed that the U.S. intervene in Mexico. ↩︎

- Houston is referring to figures in Mexico such as Antonio López de Santa Anna and other caudillos, who rose to power through military means and repeatedly destabilized Mexican governance. ↩︎

- Texas was annexed in 1845 after nearly a decade as an independent republic. This act precipitated tensions with Mexico and contributed to the Mexican-American War (1846–1848). ↩︎

- This is a subtle rebuke to sectionalism. Houston affirms that Texas joined the United States as a whole—not to align with Southern grievances or Northern ideology. He would later oppose secession on exactly these grounds. ↩︎

- This reflects Houston’s Unionist stance. As Southern states moved toward secession over slavery, Houston consistently advocated for preserving the Union, even at the cost of political isolation. ↩︎

- These references point to the national crisis over slavery. By 1859, abolitionist sentiment in the North had provoked fierce backlash in the South, leading to political polarization and the rise of the Republican Party under Lincoln. ↩︎

- Houston’s populist appeal and resistance to party machinery distinguished him. He was known for defying both Democratic and Whig establishments, prioritizing personal principle and popular will. ↩︎

- This phrase refers to national debates over slavery and abolitionism, which Houston saw as divisive and distracting. While personally conservative on racial issues, he opposed making slavery the dominant issue in state politics, as secessionists wanted to do in the lead-up to Secession and the Civil War, which Houston opposed. ↩︎

This article is part of Texapedia’s curated primary source collection, which makes accessible both famous and forgotten historical records. Each source is presented with historical context and manuscript information. This collection is freely available for classroom use, research, and general public interest.