Impeachment in Texas is a constitutional mechanism that allows the Texas Legislature to hold high-ranking officials accountable for misconduct, corruption, or abuse of power. This process serves as a check on executive and judicial authority, ensuring that public officials can be removed from office if they engage in serious wrongdoing.

While Texas impeachment proceedings share similarities with the federal impeachment process, they have unique characteristics—most notably, an official is immediately suspended from office upon impeachment by the Texas House of Representatives, unlike at the federal level, where the president retains power until convicted by the Senate.

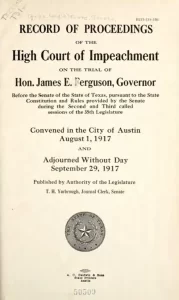

This article outlines the legal framework, process, and historical context of impeachment in Texas, detailing who can be impeached, how trials are conducted, and what constitutes an impeachable offense. It also explores past impeachment cases, such as the removal of Governor James “Pa” Ferguson in 1917.

Step One: Investigation by Texas House

The impeachment process in the Texas House of Representatives begins with an investigation into alleged misconduct by a public official. This investigation may be conducted by a House committee, such as the General Investigating Committee, which gathers evidence, holds hearings, and questions witnesses. If the committee finds sufficient grounds for impeachment, it drafts and recommends articles of impeachment, which specify charges against the official.

“Impeachment was designed, primarily, to reach those in high places guilty of official delinquencies or maladministration.”

Texas Supreme Court, Ferguson v. Maddox, 1924

Step Two: Articles of Impeachment

Once the articles of impeachment are introduced, the full House of Representatives debates and votes on them. A simple majority vote is required to approve the impeachment resolution, at which point the official is automatically suspended from office pending the outcome of a trial in the state senate.

In the strictest sense, “impeachment” refers only to this first step in a two-part process for removing an official from office. An official is impeached when a majority of the Texas House of Representatives votes to approve a resolution of impeachment, which contains “articles of impeachment” outlining specific charges against the official.

In this narrow sense, impeachment is analogous indictment in a criminal court, serving as a formal charge rather than a conviction. Customarily, however, “impeachment” also refers to the entire process of removing an official from office, including the second stage of the process, which is a trial in the Texas Senate.

Step Three: Senate Court of Impeachment

After an official is impeached by the Texas House, he or she is entitled to an “impartial trial” in the Texas Senate, according to the state constitution. This trial determines whether the impeached official should be removed from office. During the proceedings, senators act as jurors, hearing evidence, witness testimony, and legal arguments before reaching a verdict.

Members of the Texas House of Representatives are responsible for prosecuting an impeachment case before the Texas Senate. After the House votes to impeach an official, the Speaker of the House appoints a group of impeachment managers to present the case during the Senate trial. These impeachment managers act as prosecutors, introducing evidence, calling witnesses, and making legal arguments in favor of removal.

The Lieutenant Governor of Texas typically presides over the trial. At the conclusion of the trial, the senate takes a vote whether to remove or acquit the impeached official. To convict and remove the official, at least two-thirds of the senators present must vote in favor of conviction.

If convicted, the impeached official is also barred from holding future office in Texas.

The Texas Constitution Article 15 and Government Code Chapter 665 set forth the rules and procedures governing impeachment proceedings.

Officials Who Can Be Impeached

Impeachment is a procedure typically reserved for high-ranking state officers, whether elected or appointed, such as the governor or lieutenant governor; heads of government departments or institutions; and regents, trustees, or commissioners of state institutions.

However, the Texas Constitution does not identify or limit in any way the officers subject to impeachment. Braden’s Annotated Texas Constitution comments, “Arguably, therefore, the legislature has power to impeach and try any state officer except a member of the legislature (whose removal is provided for separately, in Art. III, Sec. 11).”

Comparison to Federal Impeachment

Impeachment in Texas differs in key was from the federal process.

If the Texas Legislature wants to remove a governor or other elected official, the first step is basically the same as it is in the federal system. The Texas House of Representatives holds the power of impeachment, just as the U.S. House does. By a majority vote, the legislators can impeach the official, a step that’s comparable to an indictment in a criminal court.

During the impeachment proceeding, the Texas House or one of its committees may summon witnesses, compel testimony, and punish for contempt, in the same way as a district court.

The key difference between the Texas system and the federal system is what happens after the House votes to impeach. At the federal level, the president retains his full powers even after the U.S. House impeaches him, pending his removal or acquittal by the U.S. Senate. But in Texas, once the Texas House has voted to impeach an official, that person is suspended from exercising his duties until after the outcome of a trial in the senate.

That’s what happened in 1917 when Governor James “Pa” Ferguson was impeached by the Texas House. He immediately had to hand over his powers to Lieutenant Governor William Hobby. (Ferguson’s political career didn’t end with his impeachment; he went on to run for U.S. President and U.S. Senate, unsuccessfully, and he returned to the governor’s mansion in 1925 when his wife Miriam “Ma” Ferguson won the governorship).

What Is an Impeachable Offense?

The U.S. Constitution says impeachment is for “treason, bribery, or other high crimes and misdemeanors.” The Texas Constitution doesn’t spell it out. But in several places it refers to impeachment in connection with criminal matters.

For example, the Bill of Rights (Article I) mentions impeachment in a section about the rights of the accused in criminal prosecutions. Art. IV Sec. 11, about the governor’s power of pardon, refers to impeachment as a kind of “criminal case.”

There is also a distinction made in Article XV Section 8 between impeachment and “removal by address,” a procedure involving a hearing but not a full-blown trial. Only judges and certain state commissioners can be removed in this way, for reasons of “incompetency,” “habitual drunkenness,” or other such offenses.

That language suggests that early Texans considered “impeachment” to be justifiable only for very serious conduct that was tantamount to a crime, if not actually criminal – but not for mere incompetence or “habitual drunkenness.”

Even so, later precedents established that an official can be impeached for conduct falling short of criminality. When Governor Ferguson was impeached and convicted in 1917, many but not all of the charges against him were for breaking the law.

The Texas Supreme Court defined impeachment broadly in a 1924 case, Ferguson v. Maddox. The court stated, “‘Impeachment,’ at the time of the adoption of the (Texas) Constitution, was an established and well-understood procedure in English and American parliamentary law… It was designed, primarily, to reach those in high places guilty of official delinquencies or maladministration… the wrongs justifying impeachment need not be statutory offenses or common-law offenses…”

Another impeachment case in Texas occurred in 1975, when the Duval County District Judge O.P. Carrillo was impeached for putting ghost employees on the county payroll, buying groceries with county welfare funds meant for the poor, and other misdeeds.

Carrillo was an old party boss, rancher, and third-generation heir to a local political dynasty in rural Duval County. According to the report of the House Select Committee on Impeachment, which investigated Duval, he treated the county government as his personal fiefdom and piggy bank. In addition to being impeached, Carrillo was convicted in federal court for tax evasion.

Legislative Power

The power of impeachment gives the state legislature a great deal of power. The Texas House of Representatives can suspend a governor (or other impeachable official) basically at will, at least until his acquittal by the Senate.

However, the House has only rarely exercised this power. Since the current Texas Constitution was adopted in 1876, it has impeached five state officials, two of whom were convicted by the Senate, and three who were acquitted.

The constitution also vests a great deal of power vested in the senate—and particularly in the lieutenant governor, who would serve as both acting governor and presiding officer at a suspended governor’s impeachment trial.

Braden’s Annotated Texas Constitution comments, “Permitting the lieutenant governor to preside over the impeachment trial of the governor whom he will succeed upon removal presents the potential for abuse. One remedy (would be) to require the chief justice to preside over the impeachment trial.”

In order to make that happen, the state legislature and voters would need to approve a constitutional amendment to change the process of impeachment as laid out in the state constitution.

Temporary Appointments

An official suspended by a vote of impeachment in the Texas House of Representatives may be replaced temporarily, pending trial in the state senate. The state constitution empowers the governor to make a provisional appointment replacing the impeached official.

Article 15, Section 5 of the Texas Constitution says, “All officers against whom articles of impeachment may be preferred shall be suspended from the exercise of the duties of their office, during the pendency of such impeachment. The Governor may make a provisional appointment to fill the vacancy occasioned by the suspension of an officer until the decision on the impeachment.”

Convening for Impeachment

Texas law allows the Texas House to convene for impeachment purposes even when it is not in session. That marks an exception to the general rule that the legislature cannot meet outside of regular session without being called into special session by the governor.

In order to convene in this way, the Speaker of the Texas House must issue a proclamation, after being petitioned in writing by 50 or more members of the House. Alternatively, the House may convene without the Speaker’s support, if a majority of members sign a proclamation calling for the impeachment proceeding.

Likewise, the Senate may meet for an impeachment trial even when it is not in session.