Uniquely among U.S. states, Texas was admitted to the Union with a pre-approved ‘entitlement’ to further divide itself into up to five states should it choose to do so. However, exactly how this might happen—or whether such a right really still exists—is up for some debate.

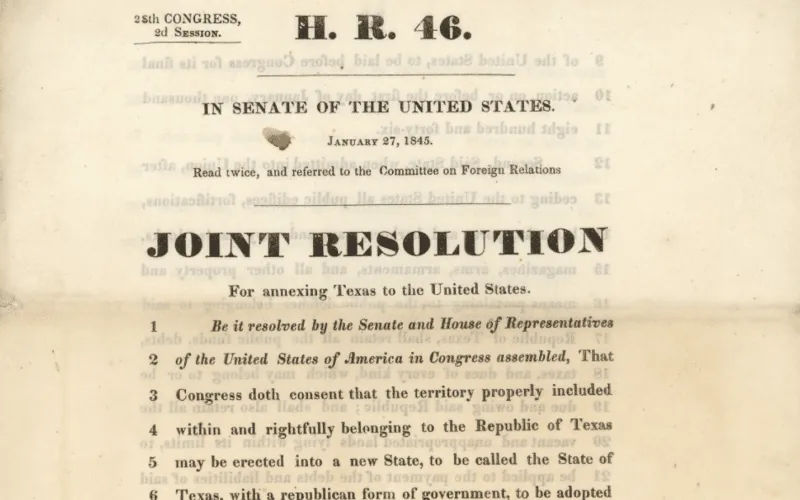

In 1845 the U.S. Congress passed a resolution annexing Texas and consenting to its statehood. The resolution included this proviso:

“New States of convenient size not exceeding four in number, in addition to said State of Texas and having sufficient population, may, hereafter by the consent of said State, be formed out of the territory thereof…”

Some Texas lawyers refer to this obscure entitlement as the “Texas Tots” clause, because it allows the mother state to create child states – ‘tots’ – out of its own territory. It was adopted not only by the U.S. Congress but by the Texas Legislature, also in 1845, when it consented to annexation.

Historical Context

For context, the joint resolution was passed after the U.S. Senate rejected an earlier Treaty of Annexation, which would have admitted Texas to the Union as a territory, not a state. Debates over slavery, expansionism, and states’ sovereignty—which culminated in the U.S. Civil War in 1861-1865—shaped the politics around the annexation of Texas.

Following the defeat of the treaty in the Senate, the expansionist Democrat Party narrowly bested the anti-expansionist Whig Party in the election of 1844. Supporters of annexation then reintroduced the proposal in Congress, this time as a joint resolution rather than a treaty, requiring only a majority vote to pass it, rather than a two-thirds majority.

After substantial political horse-trading, the annexation resolution passed both chambers. Though this was a constitutionally dubious tactic, it was never rejected by the U.S. Supreme Court, and it became the template for the annexation mechanism used in future territorial acquisitions.

Since the Republic of Texas was a slave-holding region, the prospective creation of up to four new states from its territory represented a huge boon for Democrat Party, which was mostly pro-slavery at the time. Southerners rejoiced over the annexation. The Arkansas Banner gloated in April 1845,

“Texas will come into the Union almost unanimously Democratic. It, not many years hence, will constitute four or five States—all of which will most certainly be Democratic… It is certain therefore that Whiggery is doomed… While the star of democracy has ascended the political horizon never to go down again, but to brighten with the waste of years.”1

Texas Divisionism

On the basis of the “Texas Tots” clause, some Texas politicians seriously espoused divisionism from the 1840s until the 1930s. According to the Handbook of Texas, published by the Texas State Historical Association, the Texas gubernatorial campaign of 1847 “centered around the division of Texas into East and West Texas.”2 The idea resurfaced in the Texas legislature 1852 but was defeated by a vote of 33 to 15.

Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, John Nance Garner, known as ‘Cactus Jack,’ espoused the idea as Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives and then as Franklin Roosevelt’s vice president. He told the New York Times in April 1921, “An area twice as large and rapidly becoming as populous as New England should have at least ten senators.”

After the 1930s division proposals were not taken seriously.

‘The Offer Still Stands: New States May Be Formed’

Nonetheless, a Texas Law Review article published in 2004, “Let’s Mess with Texas,” by Vasan Kesavan and Michael Stokes Paulsen, argued that Texas still retains the right under law to divide itself into smaller states. “The provision was bargained for with the sovereign Republic of Texas, and given in exchange, in part, for the latter’s agreement to enter the Union… [it] gives Texas the legal entitlement to reconstitute itself as five states, now, by simple act of the Texas Legislature, and with the consent of each of the new states thereby created.”

Malcolm Gladwell, a New Yorker writer who interviewed law professor Michael Stokes Paulsen, the co-author of the Texas Law Review article, said that his “jaw dropped” when he first learned about Texas’ right to divide itself. “This is something with a potential to turn American politics upside down,” he said in a May 2018 episode of his Revisionist History podcast. “Texans in control of American politics for the next century,” Gladwell opined, referring to the prospect of having ten Texans in the U.S. Senate.

On the podcast Gladwell comments, “Congress gave Texas permission to form another four states within its borders, which makes sense: Texas was an independent country at the time it joined the union, and a very big country at that – there were complicated political considerations in 1845 about the balance between slave states and free states. That’s a whole other story. What matters is that according to Kesavan and Paulsen’s exhaustive constitutional analysis, the offer still stands: new states of convenient size may be formed… It means that all that has to happen is for the Texas Legislature to sign off on division and it’s a done deal.”

Congressional Right to Revoke?

Crucially, however, the U.S. Constitution governs how states are admitted into the Union, and it mandates Congressional consent for the admission of new states. At issue therefore is whether the 1845 resolution already pre-clears the creation of new Texas states or else implies that further Congressional action may be necessary. The text itself says that the Texas Tots “shall be entitled to admission under the provisions of the Federal Constitution,” adding, “…such states as may be formed… shall be admitted into the Union” (emphases added).

Notably, parts of the 1845 resolution have been rendered unconstitutional by the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, because they authorized slave-holding within the Texas territories, as long as they lay south of the northern boundary of the Panhandle, a boundary then known as the Missouri Compromise Line (Texas at the time claimed territory north of its present boundary).

Controversially, Kesevan and Paulsen argued that the rest of the Congressional statute remained in effect, including the provisions governing the potential division of Texas territory: “No further legislative action by Congress is necessary for Texas constitutionally to have permission to become five Texas Tots. There may be details to work out — t’s to cross and i’s to dot. But the constitutionally necessary consent was given long ago, remains in effect today, and has not been superseded or impliedly repealed by any other provision of federal law.”

Even according to Paulsen, the U.S. Congress could withdraw its consent to Texas divisionism, if Texans ever decide to take up the matter. He told Gladwell, “Texas has to get its act together quicker than Congress can get its act together to say ‘no.’”

‘Texas Loves Its Own Bigness Too Much To Do It’

Paulsen acknowledged that the idea is pretty far-fetched: “I’ve never seen anything that suggested anybody is remotely interested in this.” Erick Trickey, a writer for Smithsonian Magazine, commented in an article in 2017, “It’s… a peculiar part of Texas’ identity as a state so big, it could split itself up—even though it loves its own bigness too much to do it.”

Notably, the pledge of allegiance to the Texas flag, which must be recited daily by school children, refers to Texas as “Indivisible”—that is, unable to be divided or separated. The pledge says, “Honor the Texas flag; I pledge allegiance to thee, Texas, one state under God, one and indivisible.”

This pledge, adopted by the state legislature in 1933, indicates that by that time, Texans had abandoned the idea of division, and viewed their state as an indissoluble unity. Furthermore, the same motto (“Texas One and Indivisible”) was adopted as the motto on the reverse of the state seal in 1961.

Therefore, even if the state has a legal right to divide in theory, it remains politically impossible, given the political culture in Texas.

- Little Rock Arkansas Banner, April 2, 1845. ↩︎

- Claude Elliott, “The History of Texas Division Proposals,” Handbook of Texas Online, Texas State Historical Association, published 1952; last updated December 1, 1994, https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/division-of-texas. ↩︎

📚 Curated Texas History Books

Dive deeper into this topic with these handpicked titles:

- Storm over Texas: The Annexation Controversy and the Road to Civil War

- Adding the Lone Star: John Tyler, Sam Houston, and the Annexation of Texas

- The Texas Republic: A Social and Economic History

Texapedia earns a commission from qualifying purchases. Earnings are used to support the ongoing work of maintaining and growing this encyclopedia.