The Jim Crow era in Texas refers to the long period between the end of Reconstruction in the 1870s and the civil rights reforms of the mid-20th century, during which racial segregation was formalized through law and custom. The term “Jim Crow” originated from a 19th-century minstrel show character, but by the late 1800s it had come to symbolize a broad legal and cultural system of racial hierarchy.

In Texas, as across the South, segregation affected nearly every facet of life, separating White and Black citizens in schools, libraries, buses, trains, housing, and the workplace. Though enforce by law, the system was also reinforced by violence, economic coercion, and a culture of exclusion.

Origins and Legal Foundations

Prior to 1865, the vast majority of Black Americans living in Texas were enslaved. At end of the Civil War, the federal government ordered the release of all slaves and granted them citizenship. This marked the beginning of a period of legal equality, though in reality Blacks were still enormously disadvantaged by the legacy of slavery. Many still lived in the same or similar conditions, in the same places, as they had prior to emancipation.

Following the end of Reconstruction in 1876, White Democratic leaders in Texas moved quickly to reassert control over state institutions and roll back the civil rights of formerly enslaved people. The Texas Constitution of 1876 omitted civil rights protections found in earlier Reconstruction-era documents and created a decentralized structure that allowed local governments wide latitude in enforcing discriminatory practices.

For a transitional decade in the 1880s, segregation existed as custom, but not law. Starting in the 1890s, state law codified segregated trains, schools, and other public facilities. In 1896, the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Plessy v. Ferguson validated the doctrine of “separate but equal,” providing a constitutional framework for segregation. Texas and other Southern states expanded their legal regimes accordingly.

New restrictions on voting, such as the poll tax and white primaries, were introduced in the early 1900s. As a result, Blacks voted in fewer numbers than they had in the 1870s-1880s, and the state stopped electing Black officials.

The 1920s witnessed a resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan and the construction of numerous pro-Confederate monuments by groups like the United Daughters of the Confederacy. Throughout the early to mid 1990s, the state legislature and local governments passed more and more segregation laws and ordinances, making the Jim Crow regime increasingly elaborate and restrictive, until the gradual dismantling of the system in the mid-to-late 1900s.

Education and Public Facilities

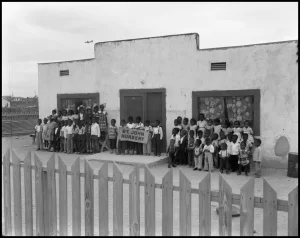

The segregation of public schools became one of the most entrenched features of the Jim Crow system. Texas statutes explicitly required school districts to establish separate facilities for White and Black children. Despite formal claims of equality, Black schools routinely received fewer resources, lower pay for teachers, and inadequate facilities.

The 1947 Independent School District v. Salvatierra case illustrated the marginalization of Mexican American students, who were often placed in “Mexican schools” under the guise of language instruction. These schools were poorly funded and isolated from mainstream education.

Beyond education, state and local governments enforced segregation in public accommodations, including waiting rooms, water fountains, theaters, and hospitals. Hospitals often maintained entirely separate wards or denied Black patients care altogether. Public parks and swimming pools were either closed to Black citizens or restricted to limited hours and substandard conditions. In many cities, entire neighborhoods were zoned informally through real estate covenants and redlining, a practice later reinforced by the federal Home Owners’ Loan Corporation and the FHA.

Voting and Political Suppression

One of the most effective instruments of racial exclusion was the denial of the right to vote. Beginning in the early 20th century, Texas adopted a series of laws designed to suppress Black political participation. These included the poll tax, the all-White primary election, and complex registration procedures.

The White primary, instituted by the Democratic Party of Texas in the 1920s, barred Black Texans from voting in the only election that truly mattered in the one-party South. Although initially upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court in Grovey v. Townsend (1935), on the basis that the primary was governed by party rules and not by the state, the practice was later struck down in Smith v. Allwright (1944). In that case, the Supreme Court held that political parties were state actors when administering primaries. Despite this ruling, voter suppression persisted through gerrymandering, intimidation, and procedural obstacles well into the 1960s.

Economic and Labor Exclusion

Black Texans faced severe economic marginalization during the Jim Crow era. The vast majority of Black workers were confined to low-wage labor in agriculture, domestic service, or manual trades. State and local governments did little to enforce labor protections in Black communities.

Labor unions often excluded Black and Mexican American workers or maintained segregated local chapters. In many industries, job postings explicitly excluded non-White applicants, and employers often paid lower wages to workers of color for the same work.

Mexican Americans also experienced segregation in employment, particularly in South Texas, where large agribusinesses depended on Mexican and Mexican American labor. Wage theft, unsafe working conditions, and racially tiered hiring practices were widespread. Legal remedies were minimal, and workers who complained were often blacklisted or subjected to police harassment.

Racial Violence and Social Control

Beyond the boundaries of codified law, violence played a crucial role in enforcing segregation. Mob attacks, arson, and racial intimidation were used to punish perceived violations of racial hierarchy, often with impunity. The Ku Klux Klan reemerged in Texas in the early 20th century, boasting tens of thousands of members and significant influence in municipal elections, school boards, and even law enforcement. Vigilantism was not uncommon, and intimidation often carried the tacit or explicit support of local officials.

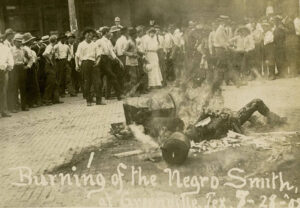

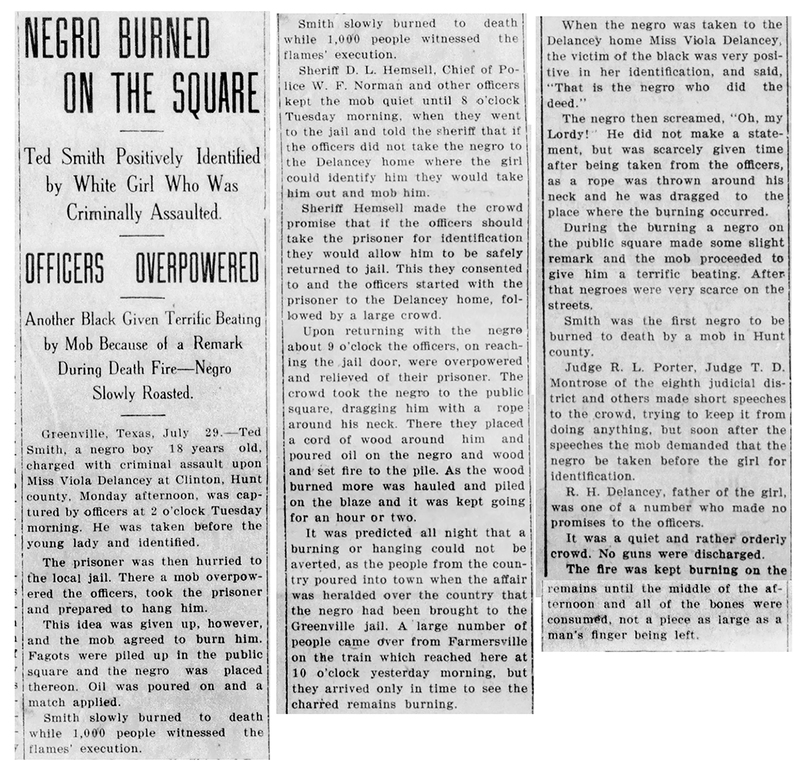

Lynching was the most visible and brutal instrument of racial terror. Between the 1880s and 1940s, Texas recorded more than 600 lynchings—placing it among the states with the highest totals nationwide. The vast majority of victims were Black men, though some Mexican Americans and others were also targeted. Alleged offenses ranged from accusations of murder or rape to minor or unproven transgressions, such as looking at a White woman or disputing a debt.

Many lynchings were held in full public view, often near courthouses or town squares, sometimes drawing thousands of spectators. In one of the most infamous cases, 17-year-old Jesse Washington was burned alive in Waco in 1916 before a cheering crowd that included city officials and children. His mutilated body was dragged through the streets and photographed, and postcards of the lynching were later circulated. No one was prosecuted.

Although national civil rights organizations repeatedly called for federal anti-lynching laws, and Texas newspapers occasionally condemned particularly egregious acts, state lawmakers failed to pass meaningful legislation. Law enforcement often handed over prisoners to mobs or simply looked the other way. Coroners issued vague or sanitized death certificates. Juries refused to indict.

The social function of lynching was clear: to deter dissent, assert White supremacy, and maintain the racial order. It was both spectacle and warning—public punishment designed to silence entire communities. In rural East Texas and urban centers alike, the fear of lynching was ever-present, constraining how Black Texans could move, speak, and act in both public and private spaces.

Law Enforcement and Carceral Labor

While mob violence drew national headlines, the everyday enforcement of racial order in Texas often relied on the quiet authority of local law enforcement. Sheriffs, constables, and police officers acted as the front line of social control, routinely targeting Black and Mexican American residents under pretexts such as vagrancy, loitering, or breach of the peace. These charges—broad and loosely defined—allowed for discretionary policing that blurred the line between legal enforcement and racial intimidation. Arrests could serve not only punitive purposes but also the symbolic reinforcement of community boundaries.

Once brought before the courts, minority defendants encountered a legal system that functioned less as a venue for impartial justice than as a tool of racial discipline. Trials were often perfunctory. All-White juries, regularly empaneled due to de facto or de jure exclusion of non-White jurors, rendered verdicts in an atmosphere shaped by local custom and prejudice. Judicial discretion in sentencing—unbounded by consistent standards—meant that Black and Mexican American defendants received substantially harsher penalties than their White counterparts for similar offenses. Appeals were rare, and even when they occurred, Texas appellate courts seldom overturned convictions rooted in racial disparities.

This judicial pipeline fed directly into a network of forced labor. Texas had one of the most extensive convict leasing systems in the South, with state prisoners leased to private firms in industries such as railroads, mining, and agriculture. Though formally abolished in 1912, the practice was soon replaced by state-run chain gangs and labor camps. Prisoners were worked under harsh conditions, often with minimal food, medical care, or sanitation. Inmate death rates were high. Black Texans, who made up a disproportionate share of the prison population, were the primary victims of this system. Penal labor became a profitable extension of racial subjugation, justified as criminal justice but serving broader social and economic functions.

Mexican American Segregation

While Jim Crow laws were explicitly directed at African Americans, many of the same legal and social mechanisms were applied to Mexican Americans in Texas. Though not classified as a separate race under the law, Mexican Americans were often treated as non-White in practice and segregated accordingly.

School segregation of Mexican American children was widespread, despite the absence of statewide legal mandates. Local districts justified separate facilities through claims of language barriers or cultural difference. In 1948, the Texas Court of Civil Appeals upheld such segregation in Del Rio ISD v. Salvatierra, although later cases—including Hernandez v. Texas (1954)—began to challenge these assumptions. In Hernandez, the U.S. Supreme Court held that Mexican Americans were a distinct class subject to discrimination and entitled to equal protection under the Fourteenth Amendment.

Resistance, Legal Challenges, and Decline

Despite the dangers, resistance to segregation in Texas was present from the beginning. Black churches, newspapers, and civic organizations provided a foundation for protest and legal action. In 1946, Heman Marion Sweatt sued the University of Texas after being denied admission to its law school. The U.S. Supreme Court sided with Sweatt in Sweatt v. Painter (1950), finding that the makeshift Black law school created by the state was not substantially equal. The decision marked an early victory in the legal dismantling of “separate but equal.”

Mexican American activism gained momentum in the 1940s and 1950s through organizations like the League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC) and the American G.I. Forum. These groups filed lawsuits, organized boycotts, and challenged school segregation and voter suppression. The Hernandez decision, the Edcouch-Elsa school walkout (1968), and the creation of the Raza Unida Party (1970) all signaled a growing Chicano civil rights movement.

The final legal unraveling of Jim Crow came in the 1950s and 1960s, driven in large part by the Black civil rights movement led by figures such as Martin Luther King Jr. Landmark victories—including Brown v. Board of Education (1954), the Civil Rights Act (1964), and the Voting Rights Act (1965)—established federal prohibitions against segregation and voter suppression.

In Texas, however, change came slowly. School districts adopted “freedom of choice” plans to delay meaningful integration. Public facilities were often desegregated quietly, with no formal announcement. In some rural counties, polling places remained inaccessible to minority voters long after federal oversight had begun.

Legacy and Continuity

While Jim Crow statutes were eventually repealed or invalidated, Blacks in Texas continued to suffer for decades from informal patterns of segregation and racism. These included racially restrictive housing covenants, exclusion from professional associations and labor unions, underfunded de facto segregated schools, and discriminatory lending and hiring practices that limited economic mobility.

Interracial marriage and interracial adoption were fairly uncommon late into the 20th century. Until 1993, the Texas child protection service (now part of DFPS) had a policy “to place children with adoptive parents whose race or ethnicity is the same as the child’s.”

Eventually, the racist ideology underpinning Jim Crow waned from view. Few Texans today still openly espouse such racial thinking. Intermarriage and immigration—both from other states and abroad—have radically reshaped Texas’s demographics. Today, the state is far more diverse and less rigidly divided than during the Jim Crow era. Black and Hispanic Texans have served in high political office, led both major political parties in the state, and taken leading roles in law enforcement and other fields. But the shadow and memory of Jim Crow still linger, shaping debates over education, culture, policing, and the criminal justice system.