The Texas National Guard has served not only in wartime but also as a cornerstone of the state’s civil protection and emergency response apparatus. From frontier defense in the 19th century to pandemic relief in the 21st, its peacetime deployments illustrate a long tradition of dual service—supporting both federal and state-directed missions.

These domestic duties have ranged from disaster response to riot control, border enforcement, and public health support, reflecting the Texas Guard’s role beyond the battlefield.

Early History and 19th Century Missions

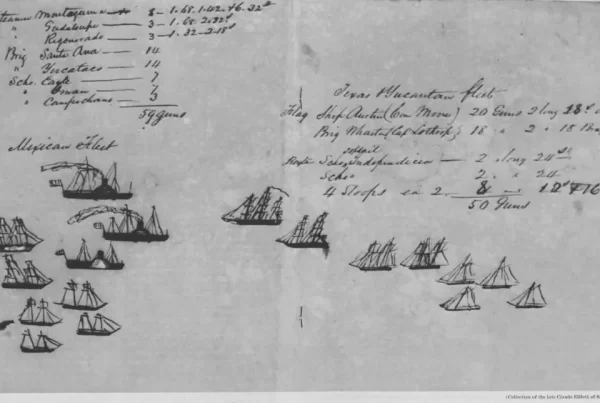

During the Republic of Texas era (1836–1845), local militia and mounted volunteer companies were the primary instruments of civil defense. These early forces responded to Native American raids on frontier settlements, helped suppress internal uprisings such as the 1838–1839 Cordova Rebellion, and engaged in sporadic skirmishes along the contested Mexican border.

After annexation, Texas continued to rely on informal militia systems until the late 19th century, when industrial strikes and episodes of racial violence occasionally prompted gubernatorial activation of state forces.

In 1842, following raids by Mexican forces into San Antonio and other frontier towns, Texas raised companies of volunteers to repel the incursions. These deployments represented some of the earliest instances of organized, state-sanctioned military response in peacetime settings. By the 1870s and 1880s, Texas governors were using state troops to:

- Break strikes in the railroad and mining industries

- Enforce curfews during epidemics

- Respond to violent unrest and racial conflicts

The federal Militia Act of 1903—often called the Dick Act—laid the foundation for transforming these ad hoc forces into a modern National Guard under shared state and federal oversight.

Border Security and Civil Support in the Early 20th Century

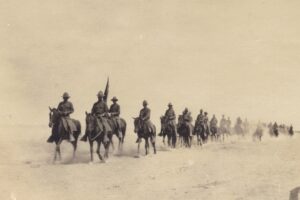

Peacetime deployments expanded in scope during the early 1900s as Texas faced recurring instability along the Mexican border. From 1910 to 1919, the Guard was mobilized repeatedly in response to the Mexican Revolution and cross-border raids.

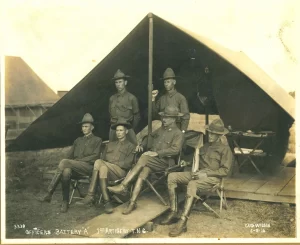

During World War I, Texas National Guard units—most notably the 36th Infantry Division—were deployed to France, where they participated in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive and other key operations during the final months of the war.

Governor James Ferguson called up troops to defend settlements in South Texas, especially after attacks by figures like Pancho Villa. These missions were coordinated with federal forces but often operated under state authority. They established a longstanding pattern of using Texas military forces to police the border during times of regional turmoil.

During the 1918 influenza pandemic, Guard armories and medical detachments were converted into emergency hospitals and quarantine sites in major cities. Personnel also supported burial teams and helped enforce public health orders. This was one of the first major public health deployments of the Guard in a peacetime context.

The interwar years also saw the Guard used to suppress labor unrest, respond to natural disasters, and protect government facilities. In the 1920s and 1930s, Guardsmen were mobilized to:

- Maintain order during oilfield strikes

- Monitor lynching threats and racial violence

- Assist during floods along the Brazos and Trinity rivers

World War II and Domestic Mobilization

During World War II, tens of thousands of Texas Guardsmen were federalized and deployed to fight overseas in major theaters of combat. Units such as the 36th Infantry Division, composed largely of Texans, saw extensive action in Italy, France, and Germany and suffered heavy casualties during the crossing of the Rapido River.

To manage domestic needs in their absence, the state created the Texas Defense Guard in 1941—a new, state-controlled force authorized by the legislature to handle internal security and emergency response. Later renamed the Texas State Guard, this force assumed responsibilities at home, including guarding infrastructure such as railway bridges, conducting blackout and air raid drills, and staffing prisoner-of-war camps that held captured German soldiers.

The Defense Guard (now State Guard) lacked the manpower, training, and resources of the federally funded National Guard and has never been as professionally equipped or institutionally significant, but it served a stopgap role during the war.

After the war ended in 1945, a particularly dramatic peacetime mission occurred in 1947 after the Texas City explosion, one of the worst industrial disasters in U.S. history. Guardsmen were mobilized to assist in firefighting, medical triage, crowd control, and recovery operations. In the postwar period, Guard units regularly responded to river flooding and storm recovery, especially in rural counties with limited emergency resources.

Deployments During the Segregation Era

During the Jim Crow era, the Texas National Guard and, later, the Texas Defense Guard occasionally played roles that reinforced racial segregation, even if less visibly than in some other Southern states. Guard units were sometimes deployed in response to racially charged unrest or demonstrations, often in ways that maintained the prevailing social order.

One early example occurred during the 1919 Longview Race Riot. After white mobs attacked Black-owned businesses and homes, Governor William Hobby declared martial law and deployed state militia units to occupy the town, enforce curfews, and restore order. Although the deployment halted further violence, Black residents were disproportionately targeted for arrest, and the Guard’s presence functioned as a stabilizing force for the segregated status quo.

Similarly, in 1943, the Texas Defense Guard was deployed during the Beaumont Race Riot, when racial tensions among shipyard workers escalated into violent attacks on Black neighborhoods. The Guard imposed martial law, established curfews, and conducted patrols, actions that again served more to control Black communities than to hold white rioters accountable.

Though less common than in other Southern states, Texas Guard units were at times mobilized to suppress unrest in majority-Black communities or to reinforce public order during racially tense episodes. While Texas avoided the high-profile confrontations seen in Arkansas or Mississippi, its military forces nonetheless contributed to maintaining racial boundaries alongside law enforcement when deployed in these contexts.

Cold War Era: Civil Unrest and Natural Disasters

The Cold War period saw a continuation of peacetime responsibilities, particularly in managing civil unrest and responding to hurricanes. During the 1960s, the Texas National Guard was placed on alert during the civil rights era, although Texas experienced fewer large-scale integration conflicts than other Southern states. In a few cases, Guardsmen were deployed to protect public buildings during school desegregation efforts in East Texas.

Student protests during the Vietnam War era also triggered precautionary Guard mobilizations. At the University of Texas at Austin and other campuses, units were stationed nearby to support local law enforcement during demonstrations, although actual deployments were limited.

Natural disasters, however, were a more frequent source of mobilization. When Hurricane Carla struck the Gulf Coast in 1961, Guard units assisted with evacuations, search-and-rescue operations, and emergency logistics. In 1967, Hurricane Beulah caused massive flooding in the Rio Grande Valley, prompting a large-scale response that included refugee shelter setup and disease control support.

Late 20th Century Operations and Institutional Growth

In the 1980s and 1990s, the Guard responded to prison riots, overcrowded correctional facilities, and infrastructure damage from major storms. During periods of unrest, they provided perimeter security and transportation support for state law enforcement. The Guard was also used during the 1983 aftermath of Hurricane Alicia, helping restore access to coastal towns and distribute supplies.

Border support became a growing focus in this period. Beginning in the late 1980s, Texas began informally using Guard units to assist in drug interdiction and immigration monitoring efforts. These operations were usually framed as partnerships with federal authorities but initiated under state authority, foreshadowing the more robust border deployments of the 21st century.

21st Century Peacetime Deployments

The scale and visibility of peacetime Guard deployments increased dramatically in the new millennium. After Hurricane Katrina in 2005, Texas Guardsmen helped house evacuees in Houston, distribute food and supplies, and coordinate law enforcement assistance. In 2008 and again in 2017 with Hurricane Harvey, they were mobilized in large numbers for water rescues, evacuation efforts, and temporary shelter operations. The Harvey deployment involved over 12,000 troops, making it one of the largest domestic mobilizations in Texas history.

Border operations also intensified. Under Governor Rick Perry, the Guard launched Operation Strong Safety in 2014 to bolster surveillance and enforcement along the Rio Grande. Governor Greg Abbott continued and expanded this approach through Operation Secure Texas and, more recently, Operation Lone Star, a sweeping mission involving thousands of Guard troops in construction, observation, and detention support roles. These deployments have sparked legal and political controversy, especially regarding the scope of state military authority and the strain on Guard personnel.

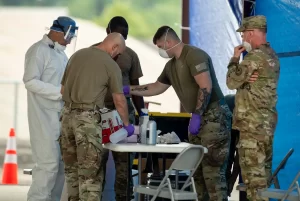

Public health missions reached unprecedented scale during the COVID-19 pandemic. Texas Guard units:

- Operated mobile testing centers

- Delivered medical equipment and PPE

- Assisted with vaccination logistics

- Transported bodies in overwhelmed counties

Their presence was essential to maintaining continuity of services in the early and uncertain months of the crisis.

Legal Foundations

Texas law authorizes the governor to activate the National Guard under state active duty in emergencies (Texas Government Code § 431.111). Guard members may also serve under Title 32 of the U.S. Code, allowing federal funding while remaining under state control. In national emergencies or wartime, they may be fully federalized under Title 10.

Peacetime deployments often raise complex legal questions, particularly when military forces are involved in civil law enforcement. The Posse Comitatus Act limits the role of federal troops in policing, but state-deployed Guard units have broader leeway, especially during declared emergencies. Still, critics argue that long-term border missions and pandemic roles test the boundaries of military-civilian separation.

An Evolving Civic Instrument

From guarding railways during World War II to navigating floodwaters after Hurricane Harvey, the Texas National Guard has evolved into a multifaceted instrument of public policy and civil defense. Its peacetime deployments demonstrate not only logistical capacity and public trust, but also the enduring flexibility of military power in a domestic context. As Texas continues to face challenges from natural disasters, health crises, and border instability, the Guard’s domestic role will likely remain both prominent and contested.