The question of secession was politically and militarily resolved in the 1860s with the total defeat of the Confederacy. After that, there has never again been a serious attempt by any state to secede from the United States of America. The cultural, political, and economic integration of Texas with the rest of the U.S. is deep—much deeper than when it seceded in the 1860s—and secession is practically out of the question.

Nevertheless, some observers wonder whether, hypothetically, U.S. states have a right to secede under the U.S. Constitution, or what scenarios could justify a secession.

Civil War Background

Texas declared its secession from the U.S. in 1861, following the election of Abraham Lincoln. The state joined ten other Southern states in forming the Confederate States of America. These states claimed the right to unilaterally leave the Union, citing federal overreach and the perceived threat to the institution of slavery.

Texas’ own declaration of secession invoked states’ rights, slavery, and racial ideology, expressing solidarity with the Deep South. The federal government, under President Lincoln, rejected these acts as unconstitutional and void. Lincoln declared in his inaugural address that “no state, upon its own mere motion, can lawfully get out of the Union.”

When Confederate forces fired on Fort Sumter, the U.S. government responded with military force to preserve the Union, initiating the Civil War. Texas supplied tens of thousands of troops to the Confederate cause, but many Unionists remained within the state, especially in German-speaking regions. The war’s outcome left no ambiguity about the federal stance: the Union was perpetual, and secession by fiat would be met with force.

The Myth of a “Special” Right to Secede

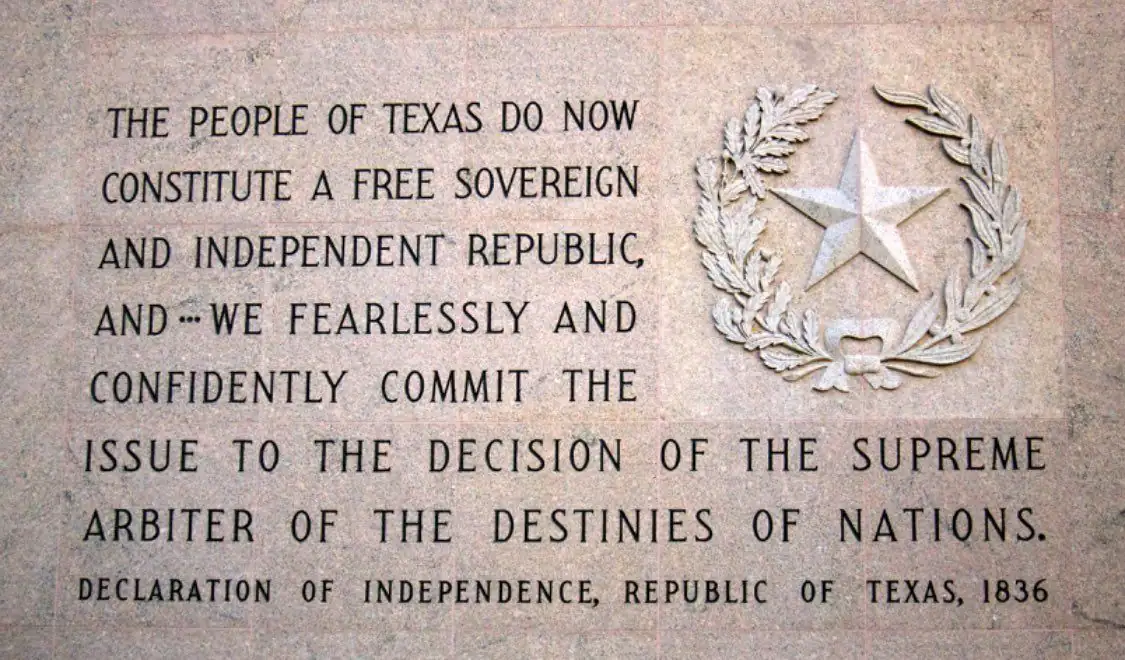

One persistent claim is that Texas has a unique legal right to secede from the United States because of its history as an independent republic. This idea is widely repeated but legally unfounded. While Texas did enter the Union in 1845 after nearly a decade as its own country, nothing in the annexation documents—neither the Joint Resolution of Congress nor the Texas Constitution—grants Texas any special ability to leave the Union.

This myth often gets confused with a different and equally misunderstood provision: that Texas can divide itself into as many as five separate states. This clause, which does appear in the 1845 annexation resolution, has nothing to do with secession. It simply allows for the possibility of Texas being subdivided into multiple states “of convenient size.” It’s a peculiar historical relic, which is explained in detailed in this article:

Texas v. White (1869): The Legal Denial of Secession

The most important legal precedent on the question of secession is Texas v. White (1869). After the Civil War, during Reconstruction, Texas sued in the U.S. Supreme Court to recover federal bonds that had been illegally transferred by Confederate officials. To hear the case, the Court first had to determine whether Texas had standing as a state in the Union.

Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase ruled that Texas had never legally left the Union, even during the Confederacy. In sweeping language, he wrote:

“The Constitution, in all its provisions, looks to an indestructible Union, composed of indestructible States.”

The Court acknowledged that states could leave the Union only through revolution or consent of the other states. In other words, secession is not a legal right but a political act—and one that carries the risk of war or requires negotiated agreement. Unilateral departure is a constitutional impossibility under the framework established by the Court.

More than a century later, the point was reaffirmed by Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia in a 2006 letter to a citizen who had inquired whether any legal basis for secession remained. Scalia replied, “The answer is clear. If there was any constitutional issue resolved by the Civil War, it is that there is no right to secede.”

Alternative Legal Theories and Secessionist Thought

Although Texas v. White remains the definitive legal precedent on secession, it has long been contested by a small but persistent current of legal and political thought—often associated with Neo-Confederate ideology, radical federalism, or constitutional revisionism. These alternative theories claim that the Union is not truly indissoluble and that the Supreme Court erred in denying states the right to withdraw.

Many such arguments rely on what is known as the compact theory of the Constitution, which treats the United States as a voluntary agreement among sovereign states. According to this view, each state retains ultimate authority to judge the limits of federal power—and, if that power is exceeded, may unilaterally revoke its consent to be governed. Though developed most famously by John C. Calhoun and other antebellum theorists, the compact theory remains popular in some libertarian and secessionist circles.

Some modern advocates pair compact theory with appeals to the Tenth Amendment, asserting that any power not expressly delegated to the federal government is reserved to the states. Others invoke the Declaration of Independence, suggesting that the right “to alter or abolish” government is not merely a revolutionary principle but a continuing natural right that might justify peaceful separation.

The federal judiciary has repeatedly rejected compact theory as a constitutional doctrine. In addition to Texas v. White, later cases such as White v. Hart (1871) and Williams v. Bruffy (1877) reaffirmed that the acts of the Confederacy were legally void, and that secession had no legal effect on the status of states within the Union.

Advertisement

Practical Barriers to Secession

Legally, any attempt by Texas to secede today would face insurmountable constitutional and political obstacles:

- Civic Tradition and National Loyalty – Generations of Americans have pledged allegiance to “one Nation, indivisible,” beginning in early childhood. That word—indivisible, meaning unable to be divided or separated—reflects more than a legal principle; it expresses a deeply held civic ideal. For many, secession is not just implausible but emotionally and morally untenable—a break with lifelong traditions of national unity and shared identity.

- Supremacy Clause and Constitutional Design – The U.S. Constitution includes detailed procedures for joining the Union (Article IV, Section 3), but no provision for leaving it. Article VI declares federal law the “supreme Law of the Land,” meaning no state can override or withdraw from the Union on its own authority. Any attempt to do so would directly contradict the structure and language of the Constitution itself.

- Economic Disruption – Texas is deeply integrated into national and global markets through U.S. trade agreements, currency systems, banking regulations, and interstate commerce. Secession would introduce enormous uncertainty in business, investment, employment, and taxation—potentially triggering capital flight, inflation, and a deep economic recession.

- Military and Security Dependence – Texas depends on U.S. military protection, intelligence, and border enforcement. Secession would require the immediate creation of a national defense apparatus from scratch—at enormous cost and with risks to public safety.

- Institutional Entanglement – Texas participates in hundreds of shared federal systems—from Social Security and Medicare to disaster response, federal courts, and environmental regulation. Untangling from these institutions would be legally and logistically overwhelming, requiring years of renegotiation, reorganization, and bureaucratic restructuring.

- Public Office and Federal Allegiance – Every elected official in Texas swears an oath to uphold the U.S. Constitution. Leading or facilitating an effort to unilaterally leave the Union would not only violate that oath—it could also be construed under federal law as inciting rebellion or insurrection, with criminal consequences.

Secession Talk in the 20th and 21st Centuries

Texas has seen periodic flurries of secession talk, especially during periods of national controversy. In the 1990s, the “Republic of Texas” group staged protests and even attempted to hold mock trials and issue currency. More recently, the Texas Nationalist Movement continues to promote the idea that Texas can and should reclaim its independence.

In 2021 and 2023, bills were filed in the Texas Legislature to allow voters to decide whether Texas should “reassert its status as an independent nation.” These measures failed to advance. In one high-profile exchange during the 2023 session, Rep. Jeff Leach (R-Plano), chair of the House Judiciary and Civil Jurisprudence Committee, sharply criticized a fellow Republican lawmaker for filing such a resolution. Leach called the proposal “ridiculous,” “dangerous,” and “anti-American,” stating that it undermined the U.S. Constitution and was unpatriotic. His remarks underscored the depth of opposition even within the Republican majority to pursuing any form of legal separation from the Union.

While a portion of the electorate may find emotional appeal in the idea of ‘Texit’, there is no serious political momentum or legal path forward. Other states—such as California, Vermont, and parts of the Pacific Northwest—have seen similar symbolic movements, often framed as responses to partisan polarization. But these movements rarely gain traction and serve more as expressions of regional frustration than as coherent political campaigns.

Why the Question Refuses to Die

It is generally accepted in American law and politics that Texas does not have a right to secede from the United States. The Supreme Court’s ruling in Texas v. White, reinforced by over 150 years of constitutional practice, affirms the permanence of the Union and leaves no legal path to unilateral departure. Practically, too, secession is an unworkable idea.

Still, a minority view persists that secession remains possible, whether through revolution, consent, or natural right. Part of the appeal lies in Texas’ peculiar history and enduring sense of exceptionalism. As a former frontier and sovereign republic, Texas has long cultivated a spirit of self-reliance and independence. The “Lone Star” mythos feeds a romantic notion that Texas might one day chart its own course again.