Few figures loom as large—or as darkly—in the popular imagination of Texans as Antonio López de Santa Anna. For generations of Texans, he has been cast in the role of villain: the tyrant who crushed the defenders of the Alamo, the general whose hubris led to defeat at San Jacinto, and the man who signed away Texas independence under duress.

Yet the man who ordered the executions at Goliad and stormed the Alamo was also a central actor in Mexico’s turbulent journey toward modern statehood. His full story reveals a complex, if no less controversial, character: a career shaped by the instability of post-independence Mexico, the shifting tides of military and political power, and his own relentless ambition.

A Country in Turmoil: The Birth of a New Nation

Antonio López de Santa Anna was born in 1794 in the Gulf Coast town of Xalapa, in what was then the Spanish colony of New Spain. He came of age at a time when revolution was in the air. Like many young men of his class, he joined the colonial army as a teenager and at first fought to suppress the independence movement. But as the tide turned in favor of the rebels, Santa Anna switched sides—an early sign of the political adaptability that would define his career.

In 1821, Mexico finally won its independence from Spain. But peace did not bring stability. Instead, the young nation fell into a prolonged period of confusion and infighting.

Elites clashed over what kind of country Mexico should be: a centralized republic, a federal union of sovereign states, or even a monarchy. The first experiment, under Emperor Agustín de Iturbide, collapsed after just two years. Santa Anna, sensing the winds of change, helped oust Iturbide and branded himself a hero of the republic.

Throughout the 1820s and 1830s, Mexico’s national politics were a revolving door of coups, short-lived constitutions, and military strongmen. Two major factions emerged: federalists, who supported a decentralized system that gave states considerable autonomy, and centralists, who favored a strong national government based in Mexico City.

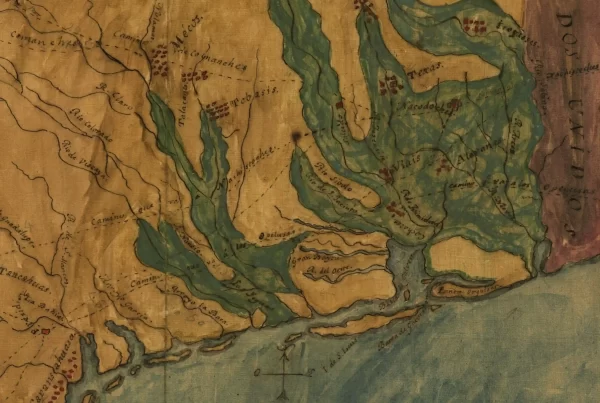

The federalist vision was enshrined in the Constitution of 1824, which shaped the early relationship between Mexico and its distant northern province—Texas. But in practice, the federalist system was fragile. Regional governors acted independently, military commanders held more power than civilian officials, and political loyalties shifted constantly. Into this instability stepped Santa Anna, an ambitious general who became a symbol of national unity for some and a manipulative opportunist to others.

The Rise of a Dictator

Santa Anna’s political star rose rapidly in the 1830s. By presenting himself as a defender of republican values, he won the presidency in 1833 with broad support. But behind the scenes, he was already plotting to concentrate power in his own hands. After assuming office, he gradually distanced himself from federalist allies and began dismantling the very system he had sworn to uphold.

By 1834, Santa Anna had dissolved Mexico’s congress, suspended the Constitution of 1824, and declared himself the head of a centralized government. State legislatures were dissolved or replaced with military appointees. Political dissent was crushed, and provincial autonomy—especially in far-flung regions like the north—was eliminated almost overnight.

Several Mexican states rebelled against this authoritarian shift. One of the first was Zacatecas, a federalist stronghold that Santa Anna’s army brutally subdued. Others soon followed. Among them was Coahuila y Tejas, the composite state that included Texas. Leaders in Texas had accepted Mexican rule under the earlier federalist system, and many Anglo-American settlers—known as Texians—had migrated under land grants issued during that period. They expected local control over laws, immigration, and taxation. But with Santa Anna’s centralist crackdown, those expectations were shattered.

In response, resistance movements began to form in Texas—not just among Anglo settlers, but also among Mexican-born Tejanos who opposed dictatorship. To the rebels, Santa Anna was no longer a distant figure in Mexico City. He was now a direct and personal threat to their rights, their land, and their future. His transformation from elected leader to self-styled strongman turned simmering tensions into open revolt.

The March to Texas: Santa Anna’s Military Campaign

Determined to crush the rebellion in Texas and reassert Mexican authority, Santa Anna decided to lead the military campaign himself—a move driven as much by political theater as by strategic necessity. Confident in his abilities and dismissive of the disorganized resistance, he believed a swift show of force would bring the region back under control and send a message to other rebellious provinces.

In early 1836, Santa Anna marched north with a large and well-equipped army, crossing the Rio Grande in winter. The campaign was harsh. His forces faced long supply lines, freezing weather, and unfamiliar terrain. But Santa Anna remained convinced of his mission: to stamp out insurrection and punish the rebels.

His first major target was San Antonio de Béxar, where a small force of Texian defenders had taken refuge in an old Spanish mission complex known as the Alamo. For thirteen days, Santa Anna’s army laid siege to the fort. On March 6, he ordered a full assault. The defenders—including William B. Travis, James Bowie, and Davy Crockett—were overwhelmed and killed almost to the last man.

To Santa Anna, the fall of the Alamo was a decisive blow meant to crush morale. But it had the opposite effect. In Texas and beyond, it became a symbol of heroic resistance and a rallying cry: “Remember the Alamo.”

Less than three weeks later, Santa Anna oversaw another notorious event—the Goliad Massacre. After capturing several hundred Texian soldiers near Coleto Creek, Mexican forces executed the prisoners under Santa Anna’s orders, despite their surrender. The massacre of Col. James Fannin’s men added to Santa Anna’s growing reputation for brutality and further inflamed Texian resolve.

Rather than pacifying Texas, Santa Anna’s campaign had galvanized it.

One poet of the Texas Revolution, writing in the Telegraph and Texas Register, captured the hatred of the Texans for Santa Anna, after the Alamo and Goliad Massacre:

"Back, back to thy covert, thou blood hound of death,

There is woe in thy step, and guilt in thy breath;

Thou warrest with women, thou curse of the brave,

Thy pity is blood, and thy mercy the grave.

"But soon the dread hour of avenging shall come..

Long ages shall roll, but thy shame shall remain...

"The aged shall curse thee, thou thirster for gore,

The worm shall be sickened with gnawing thy core,

The tombstone shall blush that points to thy grave,

Thou scorn of the wise and the brave and the true."1

Battle of San Jacinto and Captivity

In March and April, Texian forces regrouped under the command of Sam Houston, who led a strategic retreat eastward. Santa Anna pursued them, overextending his lines and growing increasingly overconfident.

On April 21, 1836, at the Battle of San Jacinto, Houston launched a surprise attack while Santa Anna’s troops were resting near the river. The battle lasted just 18 minutes. Hundreds of Mexican soldiers were killed or captured, and Santa Anna himself was taken prisoner the next day, disguised in a private’s uniform and hiding in the marsh.

With the general in captivity and his army scattered, the war was effectively over. Santa Anna, once triumphant, now found himself at the mercy of the very rebels he had tried to destroy.

Santa Anna’s time in captivity was both humiliating and politically delicate. Initially, many Texians demanded his execution for the atrocities at the Alamo and Goliad. But Sam Houston, recognizing Santa Anna’s value as a bargaining chip, spared his life. Wounded and held under heavy guard, Santa Anna was taken to Velasco near the Gulf Coast, where he entered negotiations with the interim Texas government.

There, under pressure and with no real authority, he signed the Treaties of Velasco in May 1836—one public and one secret. In them, he agreed to withdraw Mexican troops and recognize Texas independence. Though the Mexican government later declared the treaties invalid on the grounds that Santa Anna had signed them while a prisoner, his capture ended the military threat and cemented the birth of the Republic of Texas.

Despite having signed the Treaties of Velasco, Santa Anna remained a prisoner for several months as Texas leaders debated his fate. Executing him would satisfy many outraged settlers, but risk provoking further retaliation from Mexico. Keeping him in custody posed its own problems: Santa Anna was still the head of state in the eyes of Mexico, and his detention complicated efforts to gain diplomatic recognition for Texas from other nations. U.S. President Andrew Jackson, who was sympathetic to Texan independence but wary of sparking war with Mexico, quietly urged restraint.

Eventually, international pressure and political calculation tipped the balance. In December 1836, the newly elected Texas president, Mirabeau B. Lamar, remained hostile to Santa Anna and wanted him held for trial. But Sam Houston, still influential and aware of the diplomatic stakes, arranged for Santa Anna to be sent to Washington, D.C., under escort. There, he met briefly with President Jackson—though no formal negotiations took place—and reiterated his promise not to take up arms against Texas again. From there, Santa Anna was allowed to return to Mexico by way of New Orleans in early 1837.

Return from Texas and Political Comeback

Santa Anna’s capture at San Jacinto should have marked the end of his political life. Instead, it became just one chapter in a long series of dramatic exits and improbable returns. Initially, he was humiliated by his defeat, viewed widely with suspicion, and barred from returning to public office,

But by 1839, political instability created an opening. As rival factions in Mexico struggled for control, Santa Anna rebranded himself once again—this time as a champion of national unity—and maneuvered his way back into power. Between 1839 and 1855, Santa Anna served as president of Mexico an astonishing eleven times. His terms were rarely stable or long-lived; some lasted mere months, and others were conducted through puppet governments or while he ruled from behind the scenes as generalissimo.

He oscillated between federalism and centralism, sometimes positioning himself as a constitutional leader, other times ruling as a de facto dictator. Despite his political inconsistency, Santa Anna remained a skilled manipulator of public sentiment. He cast himself as Mexico’s indispensable man—someone who could rise above partisan bickering to defend the nation.

He even used personal injury to build his legend. In 1838, during the brief French invasion known as the “Pastry War,” he lost part of his left leg to a cannonball while defending Veracruz. Ever the showman, he held a grand state funeral for the amputated limb and used the episode to stoke patriotic fervor.

But Santa Anna’s erratic leadership had consequences. In 1842, he again tried to reconquer Texas, ordering the seizure of San Antonio. The raid ultimately failed, and U.S. sentiment hardened further against him. His decision to execute Texan prisoners from the Mier Expedition only reinforced his image as ruthless.

Santa Anna’s most disastrous turn came during the Mexican-American War (1846–1848). Though initially in exile in Cuba, he persuaded both the Mexican and U.S. governments to allow his return—promising peace to one and military resistance to the other. Once back in Mexico, he assumed command of the army and the presidency. He led Mexican forces in several major battles, including the defense of Mexico City, but was decisively defeated by General Winfield Scott’s campaign. After the war, Santa Anna was again forced into exile, blamed for the loss of nearly half of Mexico’s territory in the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo.

Yet he would return once more. In 1853, amid renewed instability, Santa Anna staged another comeback—this time declaring himself “His Serene Highness, the Most Excellent Antonio López de Santa Anna, President for Life of the Mexican Republic.” He ruled as an outright autocrat, squandering national funds on personal luxuries and suppressing dissent.

His most controversial act during this period was the Gadsden Purchase, in which he sold a large portion of northern Mexican territory (modern southern Arizona and southwestern New Mexico) to the United States for $10 million. Though intended to stabilize Mexico’s finances, many Mexicans viewed the deal as a betrayal of sovereignty—and suspected Santa Anna had enriched himself in the process.

Overthrow and Exile

In 1855, Santa Anna’s final grasp at power came to an end. A coalition of liberal reformers launched a successful uprising known as the Plan of Ayutla, aimed at ending his dictatorship and rolling back years of corruption, authoritarianism, and military abuse. Facing overwhelming opposition and deserted by key allies, Santa Anna fled the country once again—this time for what would become a long and mostly permanent exile.

He spent the next two decades living abroad in various countries, including Cuba, Colombia, Jamaica, and the United States. Although politically disgraced, he never gave up hope of returning to power. From exile, he penned letters to Mexican leaders and issued proclamations declaring his continued devotion to the country. But the political winds in Mexico had shifted decisively toward liberal reform, and his appeals were ignored.

In one of the more curious episodes of his exile, Santa Anna settled for a time on Staten Island, New York, where he tried to promote the commercial use of chicle, a natural tree gum from Mexico. Though his attempt to sell it as a substitute for rubber failed, American entrepreneurs would later use the substance as a base for modern chewing gum—an odd footnote in the career of a man once called the Napoleon of the West.

Isolated and aging, Santa Anna’s fortunes declined. He eventually returned to Mexico in 1874, when the government of President Sebastián Lerdo de Tejada permitted him to come home—by then blind, broke, and politically irrelevant. He lived quietly in Mexico City, where he died two years later, in 1876, at the age of 82.

The Man Behind the Uniform

Antonio López de Santa Anna was a soldier, politician, and socialite. He was known to be charismatic, charming, and conscious of his appearance—always impeccably dressed in uniform, even in exile. He relished the theater of power, holding grand receptions and donning ceremonial regalia long after his authority had faded.

Santa Anna had a lifelong love of music and gambling, often entertaining guests with music performances and once composing a waltz named after his second wife. He was a lover of fine things—silk waistcoats, military sashes, and European furnishings. He built lavish homes, including an estate in Veracruz where he kept peacocks, servants, and a private orchestra.

In his personal life, Santa Anna married twice and had many children. His first wife, Inés García, came from a wealthy Veracruz family. After her death, he married María Dolores de Tosta, with whom he lived during his years of prominence. He was known to have had multiple mistresses, and fathered children by them—a pattern not uncommon among powerful men of his era, but one that added to the perception of his excess.

Later in life, as his political fortunes declined, Santa Anna’s flamboyance gave way to frustration and nostalgia. During his exile, he lived modestly but still tried to influence world affairs. He kept writing letters to Mexican politicians, offering advice and proposing returns to power. His failed attempt to market chicle was perhaps his last venture at relevance—a far cry from the halls of power in Mexico City.

Even in obscurity, Santa Anna saw himself not as a villain or failure, but as a misunderstood patriot—a man who had given everything for his country and been betrayed by it. In modern Mexico, Santa Anna remains a divisive figure—viewed by some as a tragic nationalist who failed in impossible circumstances, and by others as a self-serving egotist who squandered his nation’s future.

- Signed, “J.E.D.,” Washington (on-the-Brazos), written May 7, 1836, published in the Columbia Telegraph and Texas Register, August 16, 1836. ↩︎