Rise to Fame: Flour, Fiddles, and Folksy Rhetoric

Wilbert Lee “Pappy” O’Daniel served as Texas governor from 1939 to 1941 and as a U.S. Senator from 1941 to 1949. A businessman-turned-radio-host, O’Daniel is best remembered for his unusual political style: a mix of homespun religiosity, anti-politician rhetoric, and musical populism.

Despite a limited record of policy achievement, he won overwhelming public support at a time when Texans—still reeling from the Great Depression—were hungry for reassurance, entertainment, and moral clarity.

His rise coincided with a broader breakdown in Democratic Party unity across Texas. While Democrats controlled virtually every statewide office, the party itself was riven by ideological divisions—between rural conservatives, New Deal liberals, business-aligned pragmatists, and urban reformers. O’Daniel’s campaign capitalized on this fragmentation by posing as a political outsider who could transcend the party’s bitter factionalism.

Before entering politics, O’Daniel achieved fame as a flour company executive and radio personality. As manager of the Burrus Mill and Elevator Company, he branded his Hillbilly Flour with wholesome Christian messaging and down-home appeal. His radio show, The Light Crust Doughboys, featured Western swing music, Scripture readings, and moral lessons. O’Daniel often closed broadcasts with a jingle that became his campaign slogan: “Pass the biscuits, Pappy!”

By the mid-1930s, O’Daniel was one of the most recognizable figures in Texas media. He used his platform not just to sell flour but to promote an idealized vision of Texas life—devout, hard-working, and community-oriented. His message resonated particularly in small towns and among working-class audiences alienated by elite urban politicians and New Deal technocrats.

The 1938 Gubernatorial Campaign

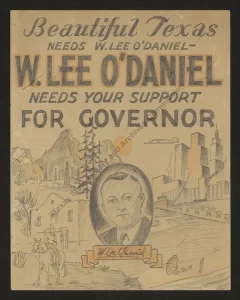

O’Daniel entered the 1938 Democratic primary for governor with no prior political experience. His platform included a vague “Ten Commandments” plan, opposition to the sales tax, support for a $30-per-month pension for the elderly, and an open Bible as a symbol of his moral authority.

Establishment Democrats dismissed him as a novelty candidate. But O’Daniel’s fame and charisma swept the state. He crisscrossed Texas by rail, drawing enormous crowds, often serenading audiences before launching into broad attacks on career politicians. He won the primary outright (without a runoff) with 51 percent of the vote—a stunning result in a crowded field that included seasoned officeholders.

His victory humiliated the Democratic leadership in Austin, which had long relied on informal networks of courthouse alliances, big-city newspapers, and business donors to control electoral outcomes. O’Daniel’s campaign bypassed all of them—relying instead on the airwaves and a cult of personality.

Political Style and Policies

As governor, O’Daniel presided more as a performer than a policymaker. He prioritized radio broadcasts and public image over legislative detail. While he did push for an old-age pension plan, his proposals lacked fiscal clarity and failed to win legislative support. O’Daniel also proposed a “transactions tax” to raise funds for the state. According to Coke Stevenson, who was the lieutenant governor at the time, the policy died for its lack of specificity:

“Governor O’Daniel was never able to explain what he meant by the ‘transactions tax.’ When you talk about a transaction, that embraces nearly everything in human activity. Whether it’s a horse trade or purchase of a milk cow or what might be the occasion, it’s a transaction, and the members of the Legislature just couldn’t fathom where the limits would be to this transactions tax. So he was never successful in getting it across.”1

O’Daniel administration operated more as a public relations machine than a functioning executive office. He held a weekly radio broadcast on Sunday mornings from the Governor’s Mansion, in which he often blamed the Legislature for his own failures, casting certain lawmakers as enemies of “the people’s will.” This constant posturing created gridlock and soured his relationship with the state’s political class.

Lieutenant Governor Stevenson later opined that the radio broadcasts “probably antagonized more than most any other device he could have used,” adding, “People who differ with you most of the time do so honestly, especially in the Legislature. They don’t like to be held up to the public as recreant to a public trust just because they happen to differ with the governor.”2

Historian Robert Caro described O’Daniel as “almost totally ignorant of the mechanics of government,” adding that he “proved unwilling to make even a pretense of learning, passing off the most serious problems with a quip. He offered few significant programs in any area, preferring to submit legislation that he knew could not possibly pass and then blame the legislature for not passing it.”3

Within the party, he became a divisive figure. Liberal Democrats and New Dealers viewed him with alarm, while conservative rural factions praised his Bible-thumping patriotism. His unwillingness to build lasting political coalitions made him a constant source of disruption rather than reform.

Clashes with Democrat Power Brokers

O’Daniel’s feud with the Texas Legislature was a hallmark of his tenure. He vetoed numerous bills and frequently accused lawmakers of corruption and cowardice. The legislature overrode 12 out of 57 of O’Daniel’s vetoes—a record. His efforts to pass comprehensive pension reform or economic legislation routinely fell apart due to poor coordination and mistrust.

Behind the scenes, the old Democratic guard—anchored by figures like Lieutenant Governor Coke Stevenson and influential urban mayors—worked to limit O’Daniel’s influence. Local Democratic machines, particularly in East Texas and the larger cities, resisted his efforts to intervene in judicial and administrative appointments. Though popular with rural voters, O’Daniel never managed to gain control of the party’s infrastructure.

His populist messaging kept the public largely on his side, but few substantial policies emerged from his administration. Even his pension plan—central to his 1938 campaign—remained unfulfilled in any durable or systematic way.

Election to the U.S. Senate

In 1941, following the death of Senator Morris Sheppard, O’Daniel ran in a special election against then-Congressman Lyndon B. Johnson. Despite Johnson’s energetic campaign and support from national Democratic figures, O’Daniel narrowly won. The race was marred by accusations of voter fraud on both sides, especially in South Texas, where ballot boxes were slow to report.

His victory was seen as a backlash against perceived elitism in Washington—and a reminder of the enduring appeal of his folksy brand. O’Daniel served two full terms in the Senate but struggled to craft meaningful legislation. He opposed much of the wartime and postwar expansion of federal government authority, but without offering a coherent alternative. Committee assignments did little to increase his influence, and his relationship with Texas’s growing liberal wing remained adversarial.

During his senate years, O’Daniel simultaneously alienated both the left and the right. He consistently attacked labor unions and some of Roosevelt’s New Deal policies. This cost him the support of many in his own party without placating business leaders and conservatives, who were embarrassed by his populism, ineptitude, and tactless attacks on a wartime president.

As his popularity declined, O’Daniel turned to fear-mongering in an effort to cling to power. He ranted about the dangers of communism and desegregation, made conspiratorial claims, and attacked fellow U.S. senators. With public opinion polls giving him only 7 percent support in 1948, he announced that he would not run again.

O’Daniel attempted a return to the governor’s office in 1956 and 1958, running as a pro-segregation and anti-communist candidate. Both times he was defeated soundly and failed even to make the Democratic primary runoff. He died in Dallas in 1969.

Legacy and Historical Assessment

Pappy O’Daniel’s political career is a study in personality-driven populism. He tapped into the anxieties and longings of Depression-era Texans, demonstrating the power of mass media in shaping political identity—decades ahead of television’s dominance.

Yet his legacy is also one of ineffectiveness. Most of his major promises went unfulfilled. Even allies came to view him as erratic and unserious.

Still, O’Daniel left a lasting impression on Texas politics, not as a statesman, but as a charismatic showman. His success marked a transition point in Texas politics—from courthouse machines and patronage networks to statewide media campaigns, from smoke-filled rooms to soundstage populism.