Oscar Branch Colquitt, governor of Texas from 1911 to 1915, was a self-made man whose political career reflected the tensions of a changing state. Rising from humble beginnings, he worked as a printer’s apprentice, edited newspapers, and entered politics as a voice for farmers and working-class Texans.

Though often remembered as a conservative governor, Colquitt rose to prominence as an outspoken critic of railroad corporations and as a leading early member of the Texas Railroad Commission, the most important regulatory agency in Texas at the time.

Early Life and Entry into Journalism

Oscar Colquitt was born on December 16, 1861, in Georgia, the son of a Confederate Army veteran who had tried and failed at farming. Seeking better fortunes in Texas, the family relocated to Daingerfield, which is near the Arkansas border.

Like many postwar southern families, the Colquitts lived in poverty. Oscar left school around age ten to support the family—working as a farmhand, porter at the train depot, and operating a turning lathe in a local furniture factory—before eventually securing a position as a printer’s devil for the Morris County Banner in 1881.

This opened the door to journalism. By his late teens, he was setting type and editing copy, learning the tools of persuasion and public communication. Despite having left school early, Colquitt continued to self-educate. He later recalled,

“I was an inveterate reader of history when I was a boy, and out of my meager earnings subscribed for a political weekly in which I read every line of politics and about what congress and public men did. This was while I was a tenant farmer in Morris County… The Reynolds farm to which we moved on Boggy Creek… had a big two-story White House and Mr. Reynold’s had left many interesting books there which I read.”1

Colquitt found steady work in journalism and eventually struck out on his own. He rented a small office in Pittsburg, Texas, used all his savings for a downpayment to buy a print press, hired one employee to work as printer, and founded The Pittsburg Gazette.

The paper expressly supported the Democratic Party, which dominated Texas politics at the time—a fact that attracted advertisers and subscribers, making the venture profitable almost immediately. In its first edition, Colquitt wrote, “Our political faith is in the Democratic Party and its principles, and we will never hesitate to express our political convictions.”2

Colquitt sold the Gazette to his younger brother in 1886 and purchased the Terrell Star, which he renamed The Terrell Times-Star. Colquitt’s editorial voice combined rural populism with an affinity for small business and low taxes. He also opined on national issues and condemned railroad corporations for exploiting farmers and called for lower freight rates. His writing helped shape his local reputation, and he soon moved into Democratic Party politics.

Early Political Career

Colquitt first served in government as a member of the five-member board of the North Texas Hospital for the Insane. Governor Jim Hogg appointed him to this position in 1891, likely to reward him for his newspaper’s outspoken support during the 1890 campaign.

He won a seat in the Texas Senate in 1894 and served from 1895 to 1899. He chaired the State Asylums Committee in 1895 the Internal Improvements Committee in 1897. His most significant bills to become law were the Delinquent Tax Bill of 1895 and a rail regulation bill of 1897, which authorized the Railroad Commission to set freight rates.

During his two sessions in the legislature, Colquitt continued managing and writing editorials for his newspapers. However, he sold the Terrell Star and announced his retirement from the newspaper business in October 1897. Colquitt opted not to run for reelection in 1898 and received an appointment instead as State Revenue Agent, having earned a reputation as an authority on Texas’s tax laws. He stepped down within a year after making a report with recommendations to Governor Charles Culberson, which influenced both Culberson and his successor.

During the 1899 and 1901 legislative sessions, Colquitt worked as a paid lobbyist for a variety of clients, including the Pullman rail car company, several investment companies, and a pharmaceutical distributor.

In 1902, Colquitt won a seat on the Texas Railroad Commission, where he developed a reputation as a regulator who pushed for lower freight rates and modest public oversight of the railroad corporations. He won reelection in 1908.

Fiscal Conservative in the Progressive Era

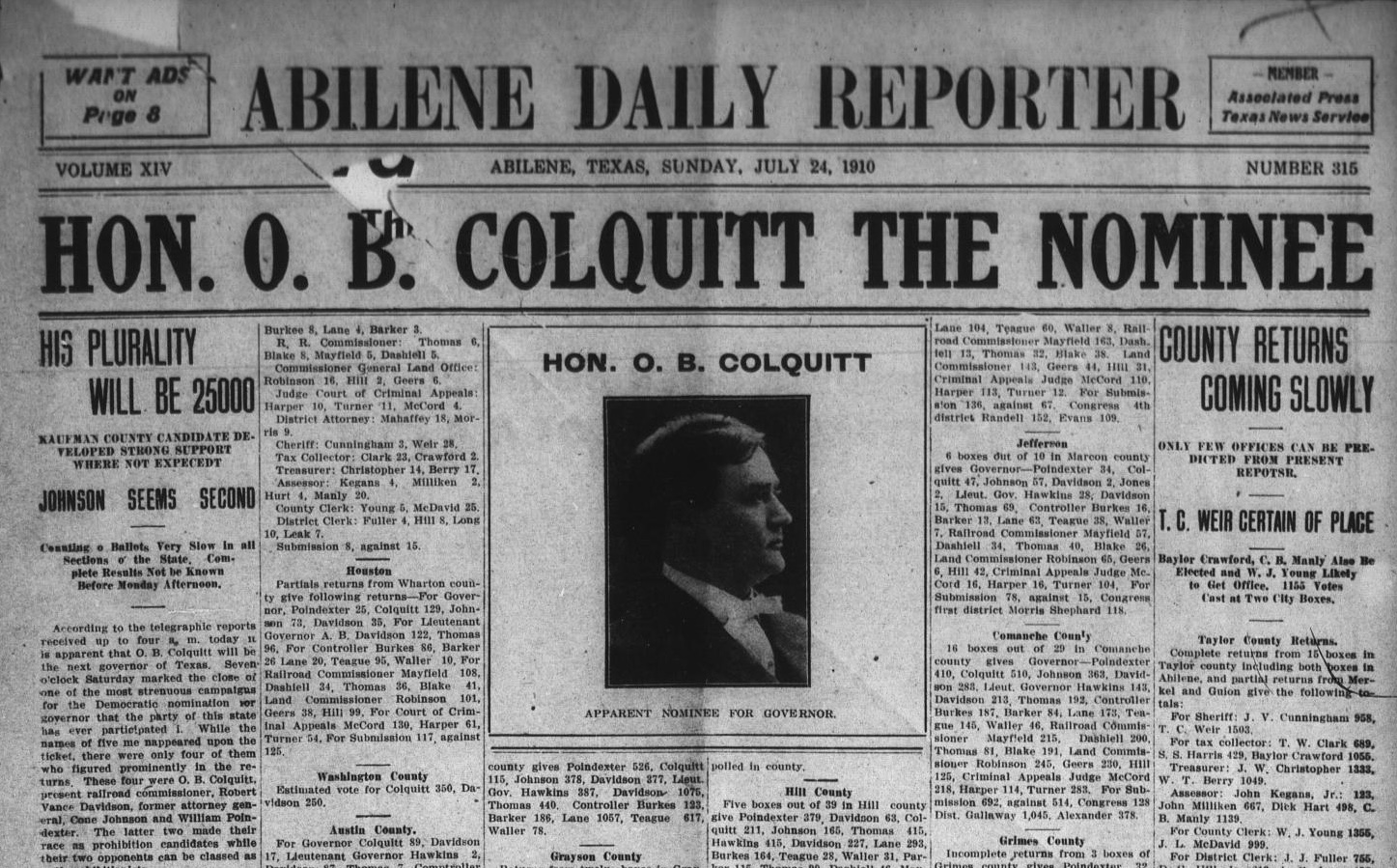

Colquitt ran for governor unsuccessfully in 1906 but tried again in 1910. He opposed alcohol prohibition, which was a hot issue at the time and on its way to becoming national law under the Eighteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution (ratified in 1919 and repealed in 1933).

Colquitt campaigned under the slogan “Political Peace and Legislative Rest,” which evoked weariness with politicians and fears that an overactive legislature might do more harm than good. This resonated with working class Texans wary moral reformers and centralized authority. In support of this position, Colquitt cited the Texas Democratic Party’s 1908 platform, which stated,

“We believe that the general welfare demands that the people shall not be annoyed by constant political agitation and they should be relieved therefrom in order that they may, undisturbed, pursue their usual avocations, to the end that they may be contented and prosperous, and we promise an intelligent and strict enforcement of the law by lawful means and the enactment of such additional laws only as are absolutely necessary to protect the public and the rights and liberties of the people.”

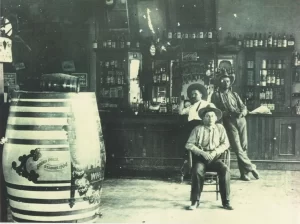

During the 1910 campaign, Texas newspapers referred to Colquitt as the “saloon candidate.”3 For example, The Matagorda County Tribune reported, “Mr. Colquitt’s backers… say he does not represent the saloons in his campaign. We would rather hear that from Mr. Colquitt (directly)… He IS the saloon candidate. The saloons are working night and day for his nomination. If he wins in the July primary, the word will go abroad, and truly, that the saloons have elected the governor of this state.”4 The newspaper also criticized Colquitt for his supposed lack of support for public school teachers and Texas A&M.

The San Antonio Daily Express, quoting Senator B.F. Looney, noted that Colquitt would likely torpedo ongoing legislative efforts to restrict or ban alcohol sales in the state:

“Mr. Colquitt’s position is well understood to be that the status quo should be maintained; that no additional laws, either constitutional or statutory, should be enacted dealing with or regulating the subject of intoxicating liquors. These being his views, if elected Governor he would no doubt veto any law designed to abolish the saloon or to regulate the traffic in any way other than the way in which it is now regulated. While there is serious diversity of opinion among lawyers as to whether the Legislature has the power under the present constitution to enact State-wide prohibition, no one anywhere questions its power to regulate the traffic to the extent of abolishing drinking saloons and to create zones around educational or other institutions within which the sale of intoxicating liquors may be absolutely prohibited.”5

Colquitt won the 1910 Democratic primary in part because the prohibition vote was split evenly between two prohibition candidates, Cone Johnson (a Progressive lawyer and former state senator) and William Poindexter (a lawyer and renowned Prohibitionist orator). Colquitt secured 41% of the votes, a plurality, which at the time was enough to secure the Democratic Party nomination for governor. He then sailed to an easy victory in the general election, taking 80% of the votes compared to 12% for the Republican candidate, 5% for a socialist, and 3% for two other candidates.

Upon taking office in 1911, Colquitt inherited a state shaped by progressive reforms but still deeply rural and conservative. His administration prioritized fiscal responsibility, and accepted moderate investments in education and infrastructure.

While not opposed to public education, Colquitt was cautious about expanding state bureaucracy. He resisted growing calls for sweeping regulatory agencies and dismissed progressive efforts that he viewed as paternalistic or driven by urban elites. In line with his campaign slogan demanding “legislative rest,” Colquitt liberally exercised the veto power during his two terms, nixing 73 bills in total.

For example, he vetoed House Bill 580 in 1913, which would have established a new agricultural experiment station, saying that the state already had 12 such stations: “It is a matter of regret to me that, in the discharge of my duty, I cannot approve of all such local measure that are presented to me by the Legislature… the expenses of our state government are growing by leaps and bounds.”

A consistent theme in his governorship was support for local control. Colquitt opposed prohibition at the state level, arguing that each county should decide for itself whether to allow alcohol sales. He also opposed certain labor rights measures. In 1911, he vetoed labor rights bill, which would have limited the work day to eight hours for laborers constructing public building.6 These positions put him at odds with rising political figures in the Progressive Era, as well as popular and influential prohibitionist organizations like the Texas Women’s Christian Temperance Union.

Labor, Race, and the Border

Colquitt’s tenure coincided with rising labor unrest and racial tensions in Texas. While he often sided with employers, he also advocated for improved conditions in factories and mines, including child labor limits and modest worker protections. As a newspaper editor, he sometimes supported strikers and pro-labor measures.

Colquitt’s record on race reflected the segregationist norms of the time. Colquitt did not challenge Jim Crow laws, nor did he support Black political participation. Like most White politicians of the era, he viewed racial hierarchy as a given, though he occasionally appealed to shared economic interests across class lines. In an editorial in the Terrell-Times Star in 1893, Colquitt condemned mob violence, following the lynching of a Black man accused of rape.

Colquitt won the support of the United Confederate Veterans during his 1910 campaign, after saying that “the policy of this state in the treatment of ex-Confederate veterans is penurious and niggardly, and since we have adopted the pension policy, we should not hesitate to give to the ex-Confederate who needs the state’s assistance a sum sufficient to keep the wolf from his door… I have said upon the stump that I believed the Washington and Lee sought for the same principles of government and the only difference between them was that Washington succeeded and Lee failed.”7

Despite his positive views of the Confederacy, Colquitt vetoed a bill in 1913 that would have erected memorials to Confederate war dead. He stated in his veto proclamation that he preferred to spend the money on the living:

“I am not averse to building these monuments. On these battlefields my relatives served their States and poured out their blood in defense of the rights of local self-government, but we have a task in Texas which calls for attention, and a tidy which demands performance in taking care of the helpless, the insane, and caring for the living who need the aid of the State’s charity. The Legislature is about to adjourn without making these provisions. The appropriations already made by this session and previous sessions have exhausted available revenues, and it is with the sincerest regret that I find it an absolute business necessity to return this bill to the House of Representatives without approval.”8

One of the most volatile issues Colquitt faced was the instability on the Texas–Mexico border during the Mexican Revolution. Concerned about violence spilling across the Rio Grande, Colquitt repeatedly urged the federal government to deploy more troops and, in some cases, acted independently to increase Texas Ranger and state militia presence.

In 1912, after a series of cross-border raids, Colquitt controversially ordered state troops to the Rio Grande without waiting for federal approval. The move earned him praise from some Texans but raised questions about constitutional limits and coordination between state and national authority.

The End of His Governorship and Later Years

Colquitt’s firm stance against prohibition remained a defining feature of his administration and a source of deep political division. Though he won reelection in 1912, his influence waned during his second term. Progressive and prohibitionist forces gained ground within the Texas Democratic Party, and Colquitt found himself increasingly isolated.

He considered running for U.S. Senate but failed to secure the nomination. After leaving office in 1915, Colquitt remained involved in business and political commentary, though he never again held elected office. He died in Dallas in 1940.

Legacy and Assessment

Oscar Colquitt governed at a time when Texas stood at the crossroads of reform and resistance. His administration was marked by a careful balancing act: encouraging business development, resisting moral legislation, and maintaining limited government while addressing public demands for better infrastructure and education.

Though often seen as a conservative, Colquitt does not fit neatly into modern ideological categories. He resisted prohibition not out of libertarianism but from a belief in local decision-making and skepticism toward elite-driven reform. He was not a populist demagogue, but he spoke to the values of rural Texans who feared overreach from cities, capitalists, or moral crusaders.

In many ways, Colquitt’s career reveals the internal tensions of Texas politics in the early 20th century—between progress and tradition, between state power and local control, and between the business class and reformers. His rise from poverty to the governor’s mansion also serves as a reminder of the ways journalism and local networks could still elevate individuals with ambition and a knack for persuasion.

Sources Cited

- O.B. Colquitt in The Pittsburg Gazette, February 16, 1934. ↩︎

- O.B. Colquitt in The Pittsburg Gazette, February 13, 1884. ↩︎

- E.g., “Colquitt Nominated by the Democrats for the Governorship: Saloon Men’s Candidate A Winner,” El Paso Herald, July 25, 1910, pg. 1. ↩︎

- “What Colquitt Stands For,” The Matagorda County Tribune, July 1, 1910, pg. 1. ↩︎

- “Campbell Swats Saloon? B.F. Looney Thinks He May Act at Special Session,” The San Antonio Daily Express, July 11, 1910, pg. 2. ↩︎

- Journal of the Texas House of Representatives, April 1, 1911, pg. 1573 ↩︎

- “Colquitt Friend of Veterans,” The Austin Statesman, July 18, 1910, pg. 1. ↩︎

- Journal of the Texas House of Representatives, April 1, 1913. ↩︎

Related Books

Dive deeper into this topic by purchasing any of these recommended books. As an Amazon Associate, Texapedia earns a commission from qualifying purchases. Earnings are used to support the ongoing work of maintaining and growing this encyclopedia.

- America in the Gilded Age: From the Death of Lincoln to the Rise of Theodore Roosevelt

- The People’s Revolt: Texas Populists and the Roots of American Liberalism

- The Victorian Internet: The Remarkable Story of the Telegraph and the 19th Century’s On-line Pioneers

- Marvels of the Texas Plains: Historic Chronicles from the Courthouse to the Caprock