In the early 1930s, the U.S. national economy collapsed, and the outlook was bleak. The stock market crash of 1929 had triggered a cascading failure of confidence—investments evaporated, credit markets froze, and businesses lost access to capital. Consumer demand plummeted.

As large firms pulled back, small businesses on Main Street shuttered, laying off workers and cutting orders. Banks failed in waves, and with no deposit insurance, depositors often lost everything.

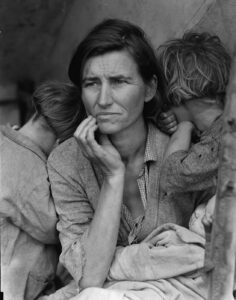

Between 1929 and 1933, the total size of the U.S. economy shrank by more than 25%. Industrial production fell by nearly half. Unemployment soared to over 24%. In cities, storefronts stood empty and breadlines stretched down the block. On farms, drought and exhausted soil turned fields to dust, while collapsing commodity prices forced thousands of families to abandon the land.

The hardship was widespread and slow-moving, eroding livelihoods over months and years. Local and state relief efforts were limited and uneven.

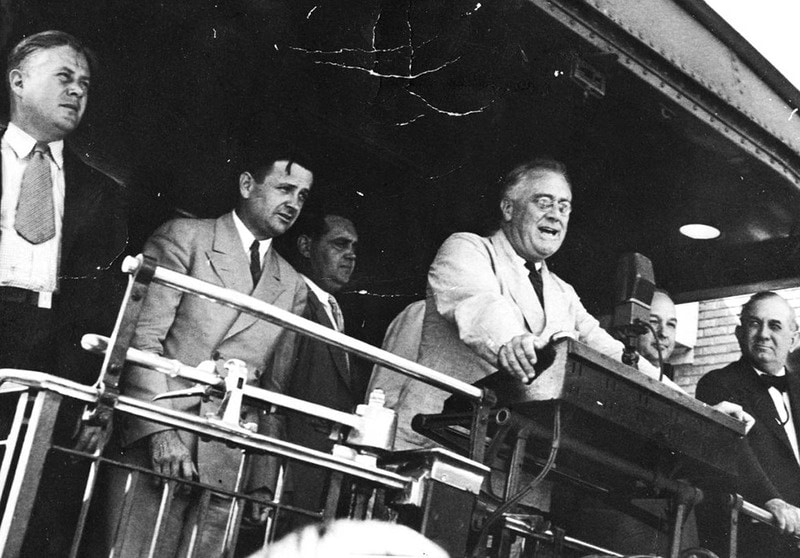

It was into this landscape that the New Deal arrived. Launched by President Franklin D. Roosevelt and his allies in Congress, the sweeping set of federal programs and reforms reshaped American political and economic life in the 1930s and 1940s.

In Texas, the New Deal brought both immediate relief and long-term transformation—ushering in new political alliances, altering the structure of state government, and setting off debates about the role of the federal government that would echo for generations.

While Texas reaped significant economic benefits from New Deal initiatives, the state’s political class responded with ambivalence, and in some cases, resistance. Over time, this ambivalence gave way to a conservative backlash that would come to define Texas’s political identity in the second half of the 20th century.

Economic Relief and Infrastructure Development

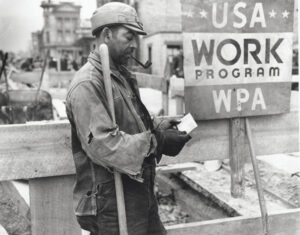

The first New Deal programs began in 1933, delivering immediate economic relief through a series of federal work initiatives. These included the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), Public Works Administration (PWA), and Works Progress Administration (WPA). Thousands of unemployed Texans found jobs building roads, bridges, courthouses, schools, and public parks. The WPA alone employed more than 600,000 people in Texas between 1935 and 1943, leaving behind a physical legacy that still shapes the state’s infrastructure today.

The New Deal’s infrastructure investments had lasting significance. Rural electrification programs expanded access to power across the Texas countryside, bringing modern conveniences to areas long disconnected from the grid. Dams and water projects—most notably the construction of Lake Buchanan and Possum Kingdom Lake—improved flood control, facilitated irrigation, and laid the groundwork for economic development. In the long term, these improvements helped integrate remote parts of Texas into the broader state and national economy.

Agricultural reforms were also critical. The Agricultural Adjustment Administration (AAA) aimed to stabilize commodity prices by incentivizing farmers to reduce crop and livestock production. This was achieved through voluntary acreage reductions and direct subsidy payments funded by a tax on agricultural processors.

Other programs included soil conservation initiatives, price supports, and the establishment of government-controlled storage and marketing systems. Together, these efforts sought to curb overproduction, restore farm profitability, and bring long-term stability to the agricultural sector.

Political Realignment in Texas

In the short term, the New Deal bolstered the Democratic Party’s dominance in Texas. Roosevelt won overwhelming support in Texas during each of his four presidential campaigns, and many Texans embraced his populist rhetoric and promises of reform. The state’s longstanding Democratic alignment—which dated to the post-Reconstruction era—now took on a more national and progressive flavor, at least on the surface.

However, the New Deal also deepened ideological divisions within the Texas Democratic Party. A rift emerged between liberal New Deal supporters and conservative Democrats who viewed federal intervention with suspicion. Figures like U.S. Representative Maury Maverick of San Antonio championed Roosevelt’s agenda, advocating for labor rights, civil service reform, and economic regulation. But they faced fierce opposition from conservative Democrats such as Governor James V. Allred and U.S. Senator Tom Connally, who supported federal relief efforts but balked at labor union empowerment and centralized federal control.

This split foreshadowed a broader realignment. By the late 1940s and 1950s, many conservative Texas Democrats began distancing themselves from the national party’s liberal trajectory. The Dixiecrat revolt of 1948 and the rise of states’ rights rhetoric in the South marked the beginning of a slow but steady shift in Texas political identity—from Democratic populism to conservative individualism.

Labor, Race, and Social Policy

New Deal labor policies had mixed effects in Texas. The National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA) and later the Wagner Act empowered labor unions nationwide, but their impact in Texas was muted by state-level resistance and anti-union sentiment. While industrial laborers in cities like Houston and Dallas gained modest protections, farmworkers—who made up a large share of the Texas labor force—were largely excluded from New Deal labor protections. Moreover, strong opposition from business leaders and conservative politicians ensured that unionization in Texas remained weak compared to northern and western states.

Racial disparities also shaped the New Deal’s impact in Texas. Many programs, particularly those administered at the local or state level, were implemented in ways that reinforced Jim Crow segregation. African American and Mexican American Texans often received fewer benefits, were paid lower wages on federal projects, or were excluded from programs altogether. The Social Security Act of 1935, for example, initially excluded agricultural and domestic workers—two major sectors of minority employment in Texas.

Nevertheless, the New Deal also laid the groundwork for later civil rights progress. By creating a federal presence in everyday life and expanding the idea of social citizenship, it subtly shifted expectations. Programs like the Fair Employment Practices Committee (FEPC), though short-lived, marked the first federal efforts to address racial discrimination in employment and sowed the seeds for future activism.

Government Expansion and Administrative Reform

The New Deal brought about significant changes in how state government operated. To administer federal programs and match federal funding requirements, Texas expanded its administrative apparatus and professionalized elements of state government. Agencies like the Texas Relief Commission and the Texas Highway Department grew in size and capacity during the 1930s, often functioning as intermediaries between federal programs and local implementation.

This growth in state administration brought lasting institutional change. The increased use of planning commissions, intergovernmental grants, and budgetary controls introduced modern bureaucratic techniques to Texas governance. Yet the experience also fed a conservative reaction. Critics warned that Texas was becoming too dependent on Washington, and that federal mandates threatened local control.

As the state emerged from the Depression and World War II with a more mature administrative structure, many of the New Deal era agencies persisted. The 1950s and 1960s brought further government growth, as the Johnson Administration waged its “War on Poverty” and Texas Democrats like Allan Shivers poured new state oil revenues into highways, mental health hospitals, schools, and universities. Government expansion continued until the Reagan era, when Republicans hardened their ideological stance against bureaucracy and regulation.

The Decline of the New Deal Order

The New Deal reshaped Texas in profound and lasting ways. It modernized infrastructure, professionalized state government, and laid the groundwork for later reforms and social programs. The physical legacy of the New Deal—roads, dams, electrification, public buildings—remains visible across the state.

While many of the New Deal’s public programs drew political backlash in later decades, some of its foundational reforms proved more enduring and less controversial. Federal deposit insurance, introduced in 1934, helped prevent future banking panics and permanently altered the relationship between citizens and the financial system. Monetary stabilization, new banking regulations, and tighter federal oversight of credit markets brought lasting changes that supported economic recovery and helped avert future collapses. Though rarely the focus of political debate in Texas, these reforms became part of the unspoken infrastructure of modern American capitalism.

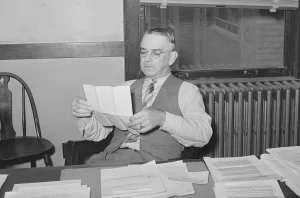

Politically, the New Deal inspired a generation of Texas progressives, including Lyndon Baines Johnson, who entered politics in the 1930s and later rose to national prominence, becoming vice president in 1961 and president in 1963. Johnson and his peers built on the New Deal legacy, expanding federal investments in education, poverty relief, and the workforce.

But Roosevelt’s policies grew increasingly unpopular in Texas in the late 1930s. By the 1940s, many Texas Democrats were actively resisting New Deal policies. Historian T.R. Fehrenbach described this shift in his 1968 bestseller, Lone Star: A History of Texas and Texans:

“In the late 1930s, the love affair between the intellectuals of the New Deal and Texas leadership began to wane. So long as the New Deal poured money into Texas and punished capitalists according to neo-Populist biases, all folk-conservatives could approve. This was functional liberalism most Texans had wanted for a long time.”

“But reforms beyond the ones grasped in the pain of the worst Depression years were not desired. Anything that suggested a broad movement of the parameters of American social institutions drew immediate hostility and fear… Roosevelt’s later proposals were anathema, and the national and state Democratic parties began to separate.”1

This growing split first erupted openly in 1944, when a group calling themselves the “Texas Regulars” tried to gain control of the state nominating convention and select a slate of presidential electors who would not vote to renominate Roosevelt. Though the attempt failed, it presaged the later Dixiecrat Revolt of 1948 and the subsequent enduring split in the party between liberals and conservatives.

As national politics grew more polarized in the 1970s and 1980s, Texas realigned sharply to the right, eventually resulting in the mass defection of Texas Democrats to the Republican Party during the Reagan and Bush years. Under Republican leadership, New Deal-style liberalism was displaced by the politics of low taxes, deregulation, and individual responsibility.

This partisan realignment changed how many Texans thought about Roosevelt’s policies. A new generation of Republicans vocally rejected the philosophical foundations of the New Deal. They reinterpreted the New Deal through the lens of welfare dependency, government overreach, and moral decline. In this view, Roosevelt’s Depression-era policies were not a necessary economic lifeline, but the beginning of a long slide into government dependency and national decline.

As a result, the New Deal, which was once so popular in Texas—sweeping Roosevelt to an 87% reelection victory in 1936—now has a contested legacy.

- T. R. Fehrenbach, Lone Star: A History of Texas and the Texans (Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press, 2000), pg. 655. ↩︎