Texas at the Center of a Continental Conflict

The U.S.–Mexico War (1846–1848), commonly known as the Mexican-American War, was a pivotal episode in the expansionist ambitions of the United States and a turning point in the history of the North American continent. Texas stood at the center of this conflict, serving as the immediate cause of hostilities, the launchpad for military operations, and the symbol of ideological and national struggle.

Annexation and the Disputed Borderlands

The roots of the conflict can be traced to the Texas Revolution of 1836, which resulted in the creation of the Republic of Texas. Despite operating as an independent republic for nearly a decade, Texas was never formally recognized as sovereign by Mexico, which viewed the territory as a rebellious province.

When the United States annexed Texas in 1845, the Mexican government was outraged, viewing this as a direct violation of its territorial integrity, though it did not take action to change the status quo, which it had accepted as

However, another outstanding point contention was the territorial boundary, and this is ultimately what triggered the conflict: while the Republic of Texas claimed the Rio Grande as its southern border, Mexico insisted that the proper boundary remained at the Nueces River, significantly farther to the north.

President James K. Polk, a staunch expansionist with a mandate to secure the Southwest and Pacific Coast, ordered General Zachary Taylor to lead U.S. forces into the disputed region between the Nueces and the Rio Grande. From the American perspective, this was a defensive maneuver to uphold Texas’s rightful claims. From the Mexican viewpoint, it was an incursion into sovereign territory—an act of war in everything but name.

The Thornton Affair and the Onset of War

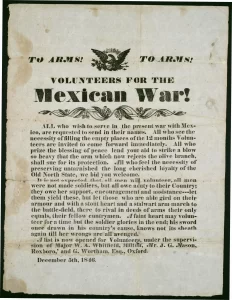

Hostilities formally began in April 1846 when Mexican cavalry attacked a U.S. scouting party in the disputed zone, resulting in several American casualties and prisoners. President Polk used the incident to galvanize public and congressional support, asserting that Mexico had “shed American blood on American soil.”

On May 13, 1846, Congress declared war, with strong Democratic backing and vocal Whig opposition. Critics of the war—including prominent legislators such as Abraham Lincoln and Senator Thomas Corwin—challenged Polk’s justification, questioning whether the encounter had truly occurred on American soil. In what became known as the “Spot Resolutions,” Lincoln demanded to know the precise location of the skirmish, underscoring the contested nature of the territory. These objections, while politically marginalized at the time, reflect the deep ambivalence that many Americans felt toward a war they viewed as imperial in nature.

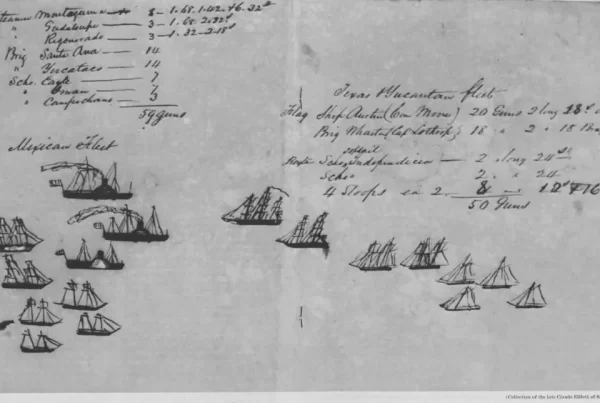

Strategic and Military Contributions from Texas

Texas’s geographic location made it indispensable to the U.S. military strategy in the northern theater of the war. Its frontier forts, inland trails, and Gulf Coast ports provided essential infrastructure for launching and sustaining the American invasion of northeastern Mexico. Corpus Christi served as a primary staging area, while cities like San Antonio functioned as supply and recruitment centers.

One of Texas’s most notable contributions came in the form of the Texas Rangers, whose irregular tactics and reputation for frontier warfare made them both valuable assets and sources of controversy. Ranger units operated as scouts and cavalry in numerous engagements, including the Battle of Monterrey and the defense of supply lines along the Rio Grande. Their actions earned praise from U.S. commanders but also drew condemnation from Mexican civilians and some American observers, who accused them of committing atrocities and operating with impunity.

Notable Texans such as Edward Burleson, Jack Hays, and Albert Sidney Johnston rose to prominence during the conflict. Their participation helped elevate the profile of Texas within the national military hierarchy, and several of these figures would later assume key roles in the Civil War—underscoring the U.S.–Mexico War’s role as a formative crucible for a generation of military leaders.

The Occupation and Rear Security

As General Taylor advanced into Mexican territory, the logistical support provided by Texas became even more critical. The Rio Grande functioned as a natural conduit for troop movement, and the overland supply routes from Texas enabled deeper incursions into cities like Matamoros, Monterrey, and Saltillo. While the eventual campaign to Mexico City would be led by General Winfield Scott via Veracruz—supplied by the U.S. Navy—Taylor’s northern campaign secured the flanks and maintained pressure on Mexico’s military.

Meanwhile, Texas itself remained vulnerable to raids and unrest. Mexican cavalry occasionally penetrated the South Texas border, keeping local militia units in a constant state of readiness. Civilians in Nueces, Webb, and Starr counties endured the economic and emotional toll of living on the war’s active frontier.

Political Resolution and Lasting Repercussions

The war concluded with the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in February 1848, by which Mexico ceded nearly half its national territory in exchange for $15 million in compensation and the assumption of certain debts. The treaty recognized the Rio Grande as the southern border of Texas, thus securing the territorial claims that had served as a principal cause of the conflict.

For Texas, the treaty marked a triumphant confirmation of its disputed sovereignty and its territorial claims to the all land north of the Rio Grande.

Yet the war’s consequences were not entirely favorable. It was remembered in Mexico as a war of imperial aggression, and the massive territorial acquisition reopened sectional conflicts over the expansion of slavery, hastening the sectional crisis that would lead to the Civil War.