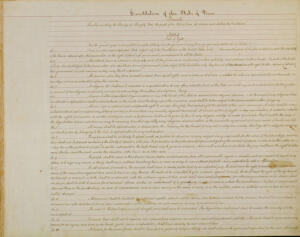

The Texas Constitution is the foundational legal document that defines the powers, limits, structure, and responsibilities of state government in Texas. First adopted in 1876, it has endured for nearly 150 years—though frequent amendments have significantly reshaped it. This article offers a concise summary of the Texas Constitution, explaining its structure, history, and key provisions in plain language.

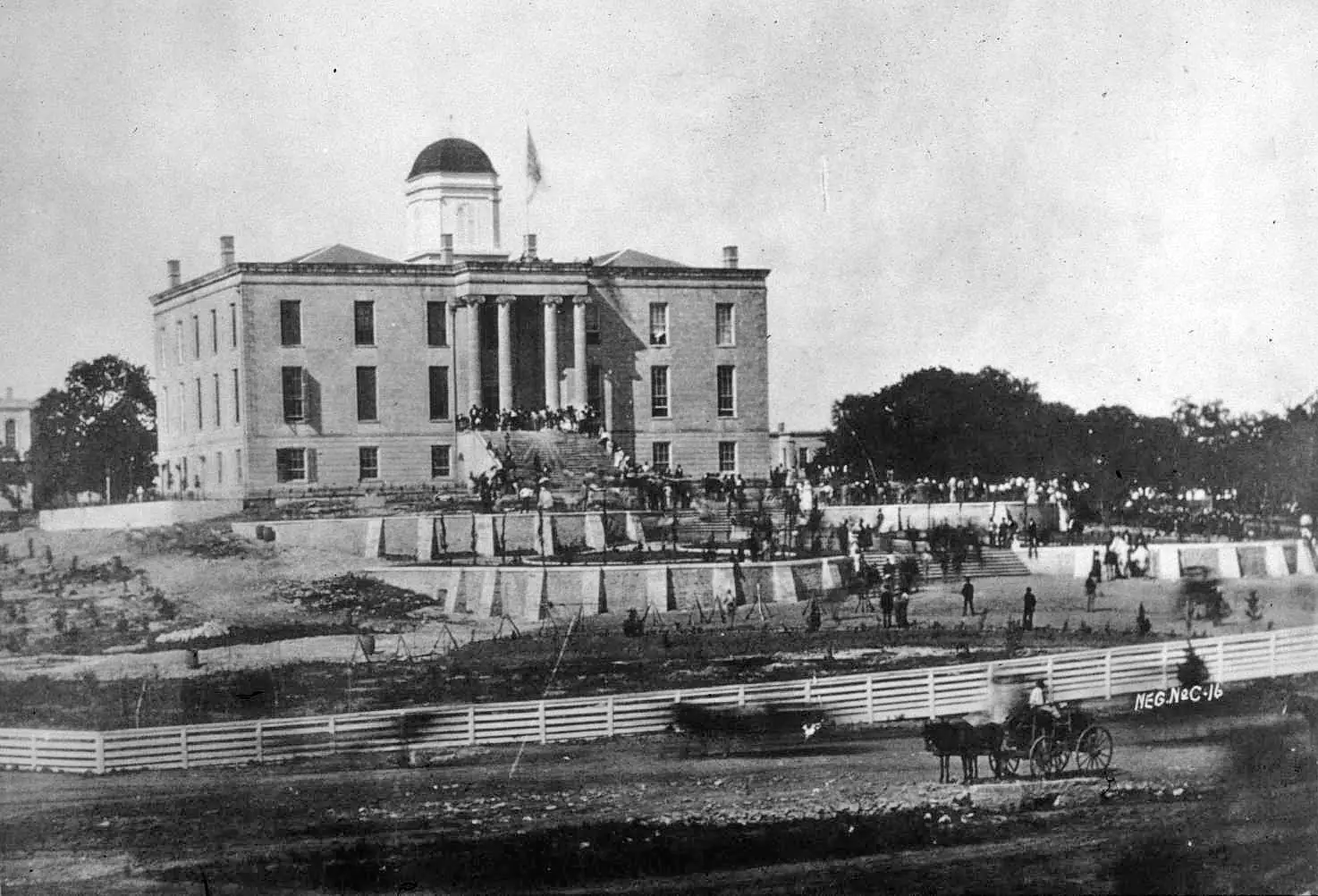

The Texas Constitution was written in a time of deep political distrust, especially toward centralized authority. In response to the perceived excesses of Reconstruction-era government, its authors designed a system that sharply limited state power. They held a convention in 1875 and presented their draft to voters—who approved—in a ratification election in 1876. The result was a government with a part-time legislature, a weak governor, elected judges, and strict controls on public institutions.

The Texas Constitution was written in a time of profound political distrust, especially toward centralized authority. Shaped by resentment of Reconstruction Era government, the 1875 convention produced a document designed to curb state power in nearly every respect. Ratified by voters the following year, it established a framework of limited government: a part-time legislature, a weak governor, elected judges, and strict oversight of public institutions.

While this structure reflected the values of post-Reconstruction Texas, it left the state with a rigid framework that can occasionally make modern governance difficult. For example, even small changes in policy often require constitutional amendments, which must be approved by voters.

Today, the 1876 Constitution still defines how Texas government operates. It has since been amended more than 500 times, yet the basic original framework remains in place. Critics contend that the Texas Constitution is too long, overly specific, and ill-suited to a fast-growing state with complex modern needs. Yet efforts to rewrite it have repeatedly failed, in large part because many Texans remain committed to the principles of local control, democratic populism, and limited government.

Studying the constitution provides insight not only into current state institutions, but also into the political values that have shaped Texas across generations.

Article-by-Article Summary

Note: This summary reflects the Texas Constitution as amended—that is, the living document as it operates today, not as it was originally adopted in 1876.

The Texas Constitution begins with a one-sentence preamble:

“Humbly invoking the blessings of Almighty God, the people of the State of Texas, do ordain and establish this Constitution.”

Article 1 of the Texas Constitution is the state’s bill of rights, which recognizes individual liberties, protecting citizens from government overreach. These include:

- Peaceable assembly: Citizens have a right to protest. However, violent assemblies (riots) are not protected.

- Freedom of worship: Citizens may worship freely as they choose, and they cannot be compelled to attend any certain place of worship.

- Freedom from unreasonable search and seizure: Law enforcement cannot search citizens or their homes without probable cause.

- Jury trial: Criminal defendants are entitled to “a speedy public trial by an impartial jury.”

- Freedom of speech: “Every person shall be at liberty to speak, write or publish his opinions on any subject, being responsible for the abuse of that privilege.” This means that citizens may speak freely but also may be held responsible in court for defamation.

Many of these rights are similar or identical to the rights enumerated in the U.S. Constitution’s Bill of Rights. For example, the Texas Constitution’s prohibition against “unreasonable searches and seizures” is essentially the same as the U.S. Fourth Amendment, except that the language is more modern.

On the other hand, several provisions are unique to the Texas Constitution. For instance, Texans are guaranteed “the right to hunt, fish, and harvest wildlife…subject to laws or regulations to conserve and manage wildlife.” The Texas Bill of Rights also defines marriage as consisting “only of the union of one man and one woman.” This section, however, was invalidated as a consequence of the U.S. Supreme Court case Obergefell v. Hodges.

Article 2 of the Texas Constitution provides for the separation of powers of the Legislative, Executive, and Judicial branches of the state government.

“The powers of the Government of the State of Texas shall be divided into three distinct departments, each of which shall be confided to a separate body of magistracy… and no person, or collection of persons, being of one of these departments, shall exercise any power properly attached to either of the others, except in the instances herein expressly permitted.”

Article 2, Section 1 of the Texas Constitution, adopted 1876

The purpose of this article is to ensure that each branch of government properly exercises its own powers, without usurping the powers of the other branches. For example, it would be improper for the legislature to rule in a criminal trial (that would be the job of the judiciary), and likewise it would be inappropriate for the judiciary to create a new law, since that is a power of the legislature.

Nevertheless, the legislative, executive, and judicial branches interact with each other in various ways, with checks and balances among them. Overall, the three branches are considered co-equal and fulfill different roles.

“The Legislative power of this State shall be vested in a Senate and House of Representatives, which together shall be styled ‘The Legislature of the State of Texas.'”

Article 3, Section 1 of the Texas Constitution, adopted 1876.

Article 3 outlines the structure, powers, and responsibilities of the Texas Legislature — the branch of state government responsible for making laws, adopting the state budget, and overseeing the use of public funds. The legislature consists of two parts, or chambers: the Senate, which has 31 members, and the House of Representatives, which has 150 members.

Article 3 also lists the qualifications required of senators and representatives, and regulates certain details of the legislative process.

Article III, Section 49 of the Texas Constitution establishes one of the state’s core spending limits by prohibiting the Legislature from incurring debt unless specific exceptions apply. In general, the state must spend within its available revenue and is not allowed to engage in deficit spending, unlike the federal government. Exceptions are limited to emergencies such as repelling invasion, suppressing insurrection, or defending the state in war. This constitutional restriction applies only to the state government; political subdivisions—such as cities, counties, and school districts—may issue debt for specified purposes under separate legal authority.

Article 3, Section 49-g establishes the state’s Economic Stabilization Fund, which is more commonly called the “Rainy Day Fund.” This fund was established after an oil bust in the 1980s, at which time state revenues were highly dependent on oil production tax.

Article 4 describes Texas’s plural executive system, which divides the executive branch into separate offices, including:

Article 4 sets forth the powers and duties of each of these officials, who are elected directly by the voters and serve four-year terms, except for the Secretary of State, who is appointed by the governor and serves a term concurrent with that of the appointing governor.

Over the years, additional offices have been added to the executive branch through law, but these six are the ones originally established by the constitution, and are still among the most prestigious and important state offices.

Governor’s Powers

The governor of Texas serves a four-year term, beginning in January after the legislature has convened. Sections 4, 5, and 6 of the Texas Constitution describe the qualifications for the office, authorize the governor to receive a salary and use the governor’s mansion, and prohibit the governor from holding other other offices, practicing a profession, or receiving extra pay from other sources while in office.

The Texas Constitution lays out various powers and duties of the governor:

- Commander-in-Chief: The Governor serves as Commander-in-Chief of Texas’ military forces, except when they are under U.S. control (Article 4, Section 7).

- Filling Vacancies: The Governor has the power to fill vacancies in state or district offices, such as district judges or district attorneys (Article 4, Section 12).

- Veto Bills: The Governor can veto bills passed by the legislature, preventing them from becoming law. The veto may be overridden by a two-thirds vote in each chamber (Article 4, Section 14)

- Call Special Sessions: The Governor can convene the Legislature for special sessions to address matters of his choosing, lasting up to 30 days. During that time, the legislature may only pass bills on matters designated by the governor in a proclamation calling the session (Article 3, Sections 5 and 40).

- State of the State Address: At the beginning of each legislative session and at the end of the term, the governor is required to providing information on the state’s condition and recommending measures for legislative action (Article 4, Section 9).

- State-Federal Relations: The Governor “shall cause the laws to be faithfully executed and shall conduct, in person, or in such manner as shall be prescribed by law, all intercourse and business of the State with other States and with the United States” (Article 4, Section 10).

- Pardons: The governor has the authority to grant pardons and reprieves to convicted criminals, but only on the written recommendation of the Board of Pardons and Paroles (Article 4, Section 11).

Additionally, the governor has certain powers granted by law, and not by the constitution. Overall, the office of governor is an important position in Texas government, but it is subject to limitations, and is generally considered weaker than the governorship in many other states.

Article 5 of the Texas Constitution outlines the structure, powers, and jurisdiction of the state judiciary, encompassing the Supreme Court, Court of Criminal Appeals, Courts of Appeals, District Courts, County Courts, and Justice of the Peace Courts.

Uniquely, Texas maintains two high courts: the Supreme Court for civil matters and the Court of Criminal Appeals for criminal cases—a distinction not found in most states.

The article also specifies jury composition for various proceedings. Felony cases require a 12-person jury, while misdemeanors are tried by six jurors. Civil juries also consist of 12 members, but only nine must agree to reach a verdict. Grand jury provisions are likewise addressed.

Article 6 defines the qualifications for voting. Any resident of Texas who is a citizen of the United States may vote in an election, except children, felony convicts prior to completion of their sentence, and persons deemed mentally incompetent by a court.

A voter must first register in order to vote. Click here to learn how to register.

Article 7 governs the system of public education in the state, as well as public universities. It allows for the creation of school districts, called independent school districts (ISDs), because they operate separately from city and county governments. Public education in Texas is provided through ISDs and public charter schools.

“A general diffusion of knowledge being essential to the preservation of the liberties and rights of the people, it shall be the duty of the Legislature of the State to establish and make suitable provision for the support and maintenance of an efficient system of public free schools.”

Article 7, Section 1 of the Texas Constitution, adopted Feb. 15, 1876.

While Article 7 of the Constitution sets forth the broad principles and fiscal framework for public education, the actual governance and administration of schools are defined by statutes, primarily in the Texas Education Code.

Article 7 also dedicates revenues from certain state sources—including portions of the Permanent School Fund and Available School Fund—to public education.

The Permanent School Fund, created in 1854 and reaffirmed in the 1876 constitution, was originally supported by the sale and lease of public lands. Today, it draws heavily from oil, gas, and mineral revenues tied to those lands.

Over time, additional constitutional amendments have clarified funding mechanisms and local control. Notably, Article 7, Section 3-e, added in 1954, authorizes school districts to levy a property tax, subject to limits set by the Legislature and contingent upon voter approval. This ties school funding directly to local tax bases.

Article 8 authorizes local governments to collect property tax, while prohibiting a statewide property tax and personal income tax. It places various restrictions on the ability of the legislature and local governments to impose taxes.

Article 8 Section 1-b establishes a residence homestead property tax exemption and regulates eligibility for the exemption.

Article Section 1-d protects farmers’ land from being appraised on the basis of the development value of the land. Land designated for agricultural use must be assessed for tax purposes “on the consideration of only those factors relative to such agricultural use.”

Article 8 Section 7-d dedicates funding from state sales tax on sporting goods to the Parks and Wildlife Department and Historical Commission.

Article 8 Section 14 establishes the office of tax assessor-collector in each county, responsible for collecting taxes, except in counties having a population of less than 10,000 inhabitants, where the sheriff of the county serves as tax collector.

Article 8 Section 22 prohibits the legislature from increasing appropriations (spending) in a biennium by more than the forecast rate of growth of the economy. However, the legislature may bypass this by passing a resolution declaring an emergency.

Article 9 of the Texas Constitution provides the basic framework for county government in Texas, including rules for the creation, structure, and certain powers of counties.

“The Legislature shall have power to create counties for the convenience of the people subject to the following provisions…”

Article 9, Section 1 of the Texas Constitution, adopted 1876.

Texas counties now number 254—the most of any U.S. state. They serve as administrative arms of the state and are responsible for a range of functions, including judicial administration, certain public infrastructure, law enforcement, and jails. Each county is governed by a commissioners court composed of a county judge and four commissioners.

Several other county officials are independently elected, including sheriffs, constables, county attorneys, and county clerks. These offices are constitutionally established but are described in Article 5 (Judiciary), not Article 9, underscoring their close connection to the justice system.

Another vital office—the county tax assessor-collector—is created under Article 8 (Taxation and Revenue). Though not part of Article 9, this officer plays a central role in managing property tax collection on behalf of counties, school districts, and other local taxing entities.

“There shall be elected by the qualified voters of each county a Sheriff, who shall hold his office for the term of four years, whose duties, qualifications, perquisites, and fees of office, shall be prescribed by the Legislature, and vacancies in whose office shall be filled by the Commissioners Court until the next general election.”

Article 5, Section 23 of the Texas Constitution, adopted 1876, amended 1954 and 1993.

Lastly, Article 9 also permits the creation of countywide hospital districts and includes miscellaneous provisions relating to airports and mental health services—provisions that were added by constitutional amendment and were not part of the original 1876 text.

Overall, Article 9 is quite brief, leaving most of the day-to-day structure and operations of county government to be defined by state statutes, especially the Texas Local Government Code.

Article 10 is only two sentences long and deals with railroads. It declares that railroads are “public highways” and that railroad companies are “common carriers.” Article 10 also empowers the legislature to pass laws to regulate railroads, freight, and passenger tariffs, “to correct abuses and prevent unjust discrimination and extortion in the rates.” Another eight sections of Article 10 were repealed in 1969.

Article 11 of the Texas Constitution addresses the organization of municipalities (cities), but provides only a broad constitutional framework.

Cities in Texas are classified as either general-law or home-rule municipalities. General-law cities—those with a population of 5,000 or fewer—may exercise only those powers expressly granted by state statutes. Cities with more than 5,000 residents may adopt a home-rule charter, giving them broader authority to govern local affairs and structure their own government.

City charters may be adopted or amended by majority vote in a charter amendment election, though such changes may not occur more frequently than once every two years.

While Article 11 remains the constitutional basis for municipal governance, much of the present-day legal structure is codified in the Texas Local Government Code, which was developed long after the Constitution of 1876 and reflects the evolving complexity of urban administration.

Article 12 contains two sections directing the Legislature to enact general laws for the formation of private corporations and prohibiting their creation by special law.

These rules were adopted in the late 1800s to prevent political favoritism and backroom deals, ensuring that all corporations are formed under the same legal framework. This marked a move toward greater consistency and public accountability in how businesses are chartered in Texas.

Article 13, aimed to address the validity and rights associated with land titles granted by Spanish and Mexican authorities before Texas became part of the United States.

Over time, the need for these specific provisions diminished as land title disputes were resolved. Consequently, the article was deemed obsolete and was repealed in 1969.

Article 14 establishes the Texas General Land Office and the position of Land Commissioner. The Land Office keeps all land titles and manages millions of acres of state land. Article 14 is only two sentences long. Most of it was repealed in 1969.

Article 15 describes the process of impeachment, by which corrupt or negligent officials can be removed from office. Impeachment is a two-step process, starting with an investigation the House of Representatives and then a trial in the Senate.

Unlike the federal system of impeachment, in Texas, all officers impeached by the House are suspended until a verdict by the Senate has been delivered.

Article 16 contains miscellaneous provisions, including the following:

- Section 1 describes the oath of office for all officers of the state.

- Sections 2 and 5 bar persons convicted of bribery, perjury, or forgery from holding office, reflecting the Constitution’s emphasis on integrity in government. These provisions apply regardless of whether the offense occurred in or outside official duties.

- Section 6 limits appropriations for private purposes, reflecting post-Reconstruction concerns about government corruption and the misuse of public funds. It was intended to prevent the state from granting financial favors to railroads, land speculators, and other private interests at public expense.

- Section 9 secures the residency rights of Texans living out-of-state on federal business.

- Section 10 allows for deductions from public officers’ salaries for neglect of duty.

- Section 11 allows the Legislature to fix maximum interest rates under Texas usury law. If no rate is set by law or agreed to in a contract, a default rate of 6% per year applies. Most interest rates today are governed by contract or by the Texas Finance Code, which provides more detailed usury regulations for commercial and consumer loans.

- Section 12 bars members of Congress from holding state office, preventing individuals from simultaneously serving in both state and federal government.

- Section 13 allows for unopposed candidates take office without an election.

- Section 14 requires all civil officers to reside in-state, and all district or county officers within their districts or counties, or else to vacate the office held.

- Section 15 defines separate and community property of spouses, stating that most property acquired during marriage is community property, while property owned before marriage or received by gift or inheritance is separate. This distinction matters in divorce, where only community property is divided.

- Section 26 creates civil liability for homicide, allowing surviving family members to sue for damages in addition to any criminal charges.

- Section 28 prohibits garnishment of wages. This protection dates to the 1876 Constitution and was originally intended to shield working-class Texans from creditors, though voters later approved amendments to allow garnishment for court-ordered child support and spousal maintenance.

- Section 30 says, “No person shall be denied the opportunity to work based on membership in a labor union or non-membership in a union.”

- Section 37 grants mechanics and tradespeople a lien on buildings they repair or improve, securing payment for their labor or materials provided.

- Section 41 defines bribery and solicitation of bribery.

- Section 50 provides for protection of a homestead against forced sale to pay debts, except for foreclosure on debts related to the homestead, such as a mortgage.

- Section 59 allows the Legislature to create conservation and reclamation districts with authority to levy taxes and issue bonds for water, flood control, parks, and other resource projects. Voter approval is required for debt, and special laws must follow public notice and local consent rules.

- Section 67 authorizes the legislature to establish benefit programs for state and local public employees, such as the Employees Retirement System of Texas.

Article 17, the final part of the Texas Constitution, lays out a two-step process by which the constitution may be amended. Two-thirds of the members of each chamber of the legislature must approve the proposed amendment, after which it must be ratified in a general election.

Explore Further

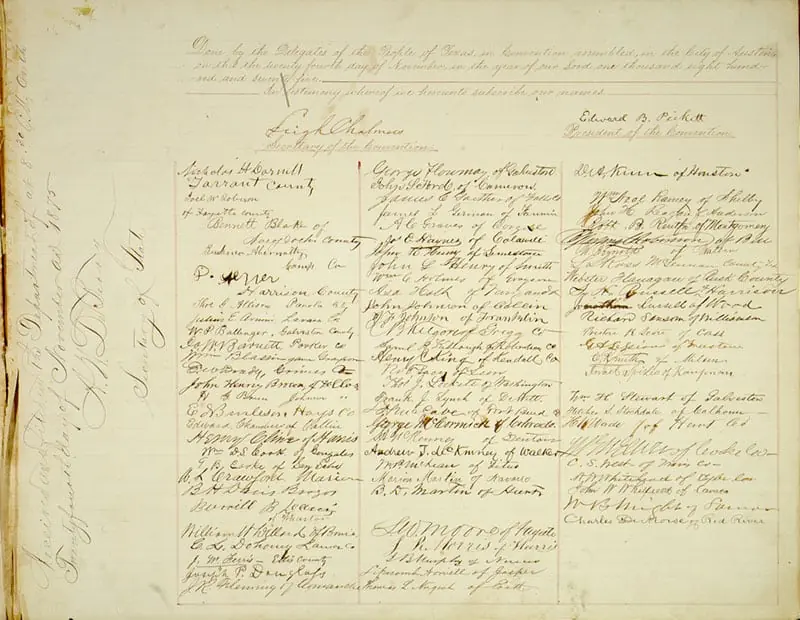

- Read about the Constitutional Convention of 1875.

- Read about predecessor constitutions.

- Explore our Texas Civics 101 series.