After the Civil War, Texas entered a tumultuous period of Reconstruction (1865–1874) under federal oversight. In this era, the state was compelled to rewrite its governing charter to extend rights to formerly enslaved people and reshape political power. The result was the Texas Constitution of 1869, a document born of military occupation and Radical Republican ideals.

This article explores the origins of the 1869 constitution, the contentious convention that drafted it, its key provisions, the administration of Governor Edmund J. Davis under its authority, and the fierce resistance that led to its abandonment in favor of the Constitution of 1876. Comparisons between the 1869 and 1876 charters illustrate how Reconstruction’s legacy still echoes in modern Texas governance and political identity.

Origins: Congressional Reconstruction and Military Rule

In 1865–1866, Texas had initially attempted to rejoin the Union under lenient Presidential Reconstruction policies. A state convention in 1866 drafted a constitution that acknowledged the end of slavery but refused to grant civil or political rights to Black Texans. This approach fell short of new federal requirements.

On March 2, 1867, the U.S. Congress responded by passing the First Reconstruction Act, which invalidated the 1866 Texas government and imposed military rule. Texas, along with other former Confederate states, was placed in the Fifth Military District under General Philip H. Sheridan’s command.

Under the Reconstruction Acts, readmission to the Union required Texas to craft a new constitution guaranteeing African American men the right to vote and acknowledging the supremacy of federal law. Military authorities removed ex-Confederate Governor James W. Throckmorton as an “impediment to Reconstruction” and appointed Elisha M. Pease, a Unionist Republican, as provisional governor.

By late 1867, registration of voters—including thousands of freedmen—and an election for a constitutional convention were orchestrated by the U.S. Army. Conservative Texans decried these measures; in January 1868 a group of former Confederates meeting in Houston even declared they “preferred military rule to the ‘Africanization’ that would result from a convention” if Black men participated. Despite such opposition, Reconstruction officials proceeded to call a convention in compliance with federal law.

The Constitutional Convention of 1868–69

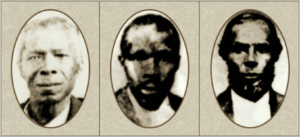

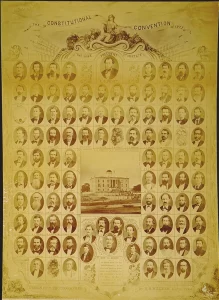

On June 1, 1868, ninety elected delegates assembled in Austin to draft the new constitution. Notably, the convention was dominated by Republicans and included ten African-American delegates out of the ninety—among them prominent Black leaders like George T. Ruby of Galveston. This marked the first time in Texas history that Black men participated in constitution-making, a direct result of federal requirements and Black voter mobilization (nearly 40,000 Black Texans voted in favor of holding the convention). The remaining delegates were White Unionists or southern Republicans (often derided as “scalawags” by opponents), along with a minority of Democrats.

The convention quickly split into factions along ideological lines. Moderate Republicans led by figures like Andrew J. Hamilton (the ex-Provisional Governor) and Gov. Pease formed one bloc, generally supporting law-and-order, business interests, and basic civil rights for freedmen. Radical Republicans, led by Edmund J. Davis (a Union Army veteran) and Morgan C. Hamilton, comprised another bloc; they pressed for more expansive rights for Black Texans and stronger federal alignment. Two other Republican factions also emerged – one led by James W. Throckmorton’s former allies pushing economic development and even division of the state, and another smaller group often aligning with the radicals or moderates as issues arose.

Democrats were few in number, since many ex-Confederates had been disqualified or boycotted the process, but those present acted as swing votes, occasionally teaming with one Republican faction to curb the ambitions of another.

The convention’s work was chaotic and slow. It remained in session until February 1869, devoting as much time to special-interest legislation as to the constitution itself. Delegates wrangled over issues like state debt, law enforcement, and racial equality under intense political pressure. After some 150 days of debate (versus only 55 days for the 1866 convention) and at a cost of over $200,000, the convention failed to formally agree on a final constitution. In late February 1869 the assembly broke up in confusion without adjourning sine die, with barely half of the delegates signing the draft document.

Amid the deadlock, General J. J. Reynolds, the military commander in Texas, stepped in. Acting under federal authority, Reynolds treated the convention’s draft as the official constitution and ordered it published and submitted to voters, despite its irregular adoption. This unprecedented intervention ensured that Reconstruction’s mandates would not be thwarted by local obstruction: the so-called “Constitution of 1869” would be presented to the people whether the Texas delegates concurred or not.

Key Features of the 1869 Constitution

Although born in controversy, the 1869 Constitution introduced sweeping changes to Texas governance and law. Drafted by a coalition of moderate and radical Unionists, it was by far the most nationalist and reform-oriented constitution Texas had ever seen. Several key features set it apart:

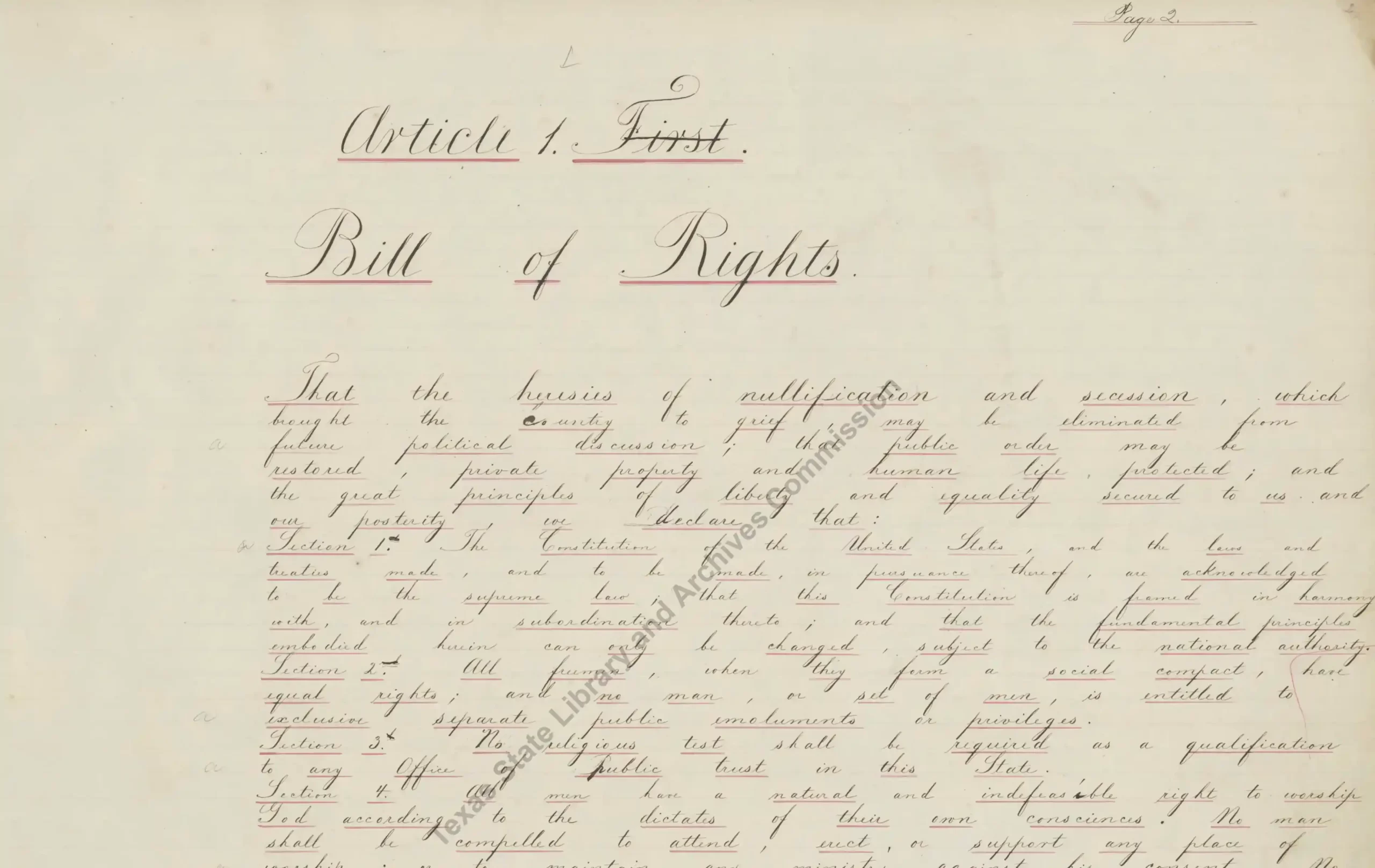

Supremacy of U.S. Law

In its very first article, the 1869 Constitution explicitly acknowledged the U.S. Constitution as the supreme law of the land and declared the Texas government subordinate to federal authority. This was a radical departure from earlier Texas constitutions (which had emphasized state sovereignty) and was intended to repudiate the “heresies of nullification and secession” that had led to Civil War. The document even stated that its own provisions could only be changed “subject to the national authority,” embracing the idea that ultimate sovereignty resided with the United States.

Expanded Voting and Equality

Meeting Congressional demands, the new constitution guaranteed voting rights to Black men. It defined the electorate as “every male person” 21 or older who was a U.S. citizen (or in the process of becoming one), resident in Texas for one year, without distinction of race or color. This effectively enfranchised Black Texans (and disenfranchised none on the basis of race), going beyond the 1866 constitution which had explicitly limited voting to white men.

The 1869 charter also incorporated the 14th Amendment’s equal protection principles, pledging “the great principles of liberty and equality” for all and outlawing slavery and involuntary servitude except as criminal punishment. It further forbade any future “system of peonage” or importation of contract laborers (so-called “coolies”), to prevent exploitation of workers in quasi-slavery conditions.

Centralized Executive Power

The framers of 1869 greatly strengthened the powers of the governor relative to previous Texas constitutions. The governor’s term remained four years, but importantly the governor gained authority to appoint major state officers and judges (with Senate consent) rather than having them elected. The entire judiciary – Supreme Court justices and district judges – would now be appointed by the governor for lengthy terms, replacing the elective judiciary of the 1866 constitution. This was meant to enforce uniform justice and suppress ex-Confederate influence in local courts.

The governor’s appointment power also extended to the Secretary of State and Attorney General, although other executive offices (Treasurer, Comptroller, Land Commissioner) remained elective. Additionally, the legislature was authorized to empower the governor to suspend habeas corpus in cases of rebellion or invasion (subject to legislative act), a provision that, combined with broad militia powers, gave the executive tools to quell violent resistance. Overall, the constitution’s centralizing tilt led one historian to label it an “autocratic” framework in practice.

Public Education Mandate

For the first time, Texas’s constitution made establishing a statewide system of free public schools a constitutional duty. The 1869 document required the legislature to create school districts and elected school boards and to provide a “uniform system of public free schools” for all children between 6 and 18 years, regardless of race. It even mandated compulsory attendance and a minimum school term of four months per year.

To fund education, the constitution set aside the proceeds from public lands into a Permanent School Fund and further required one-fourth of annual state tax revenue and a $1 poll tax on every adult male to be dedicated to schools. These measures dramatically expanded state responsibility for education and guaranteed, on paper, the first public schooling opportunities for Black Texans alongside whites (though segregation was not explicitly addressed and would later be imposed by statute). The 1869 education provisions reflected Radical Republicans’ belief in state activism for social uplift; such specificity in the constitution about school governance was unprecedented.

Limits on Corporations and Local Governments

In line with Radical suspicion of the old planter class and railroad barons, the constitution sought to curb corporate privilege and focus resources on citizens. It prohibited the legislature from granting public lands to private corporations (like railroads) and declared that any unfulfilled land grants to railroads would be forfeited if project terms weren’t met. This signaled a break from antebellum development policy and aimed to reserve land benefits for settlers and public needs (especially schools).

Additionally, by centralizing the appointment of judges and some officials at the state level, the 1869 charter reduced local control over offices that traditionally had been locally elected, such as the judiciary. All county judges and many municipal officers fell under increased state oversight (either by appointment or by state-defined uniform election rules).

Even elections themselves were tightly controlled: the constitution specified that all elections be held at county seats and over four days, an unusual rule (written with a contentious semicolon in the text) that aimed to standardize voting but drew criticism from Democrats who later challenged its wording in court (the famed “Semicolon Court” controversy). In sum, the document’s thrust was to check the autonomy of local governments and align them under state supervision, a reaction to the fierce resistance pockets where ex-Confederates still held sway.

Voter Ratification of the 1869 Constitution

Texas voters finally had the opportunity to weigh in on this new constitution in late 1869. In a tense election held under federal military supervision, the Constitution of 1869 was ratified by popular vote (albeit by a narrow margin) and a full slate of state officials was elected. On January 11, 1870, General Reynolds certified the election results: the constitution had been approved and Edmund J. Davis had won the governorship by about 800 votes.

With that, Texas met the congressional requirements. Two months later, on March 30, 1870, President Ulysses S. Grant signed the act formally readmitting Texas to the Union. The Reconstruction Constitution of 1869 was now the law of the land in Texas, inaugurating a new government with sweeping powers to reshape the state.

Edmund J. Davis: Governing Under the 1869 Constitution

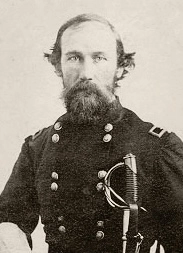

The prime beneficiary of the new order was Governor Edmund J. Davis, who took office in early 1870. Davis was a Florida-born Texan who had remained loyal to the Union during the Civil War, raising a regiment of Unionist Texas cavalry. As a leader of the Radical Republicans in Texas, he had presided over the 1868–69 convention and now, at age 42, became the first governor under the Reconstruction constitution. The 1869 constitution’s centralization of authority enabled Davis to pursue an ambitious (and to his opponents, infamous) reform agenda during his term (1870–1874).

Under Governor Davis, the state government wielded unprecedented centralized power. Davis moved aggressively to enforce civil rights and defend the new interracial democracy in Texas. For example, with legislative approval he created the Texas State Police, a statewide integrated police force to combat lawlessness and Ku Klux Klan violence. This force, along with a state militia under Davis’s control, was empowered to implement martial law in disorderly counties and arrest offenders, something traditional local sheriffs often refused to do in cases of white violence against Black citizens.

Davis’s administration also poured resources into the newly mandated public school system, including schools for Black children – a venture funded by the new poll tax and land revenues as required by the constitution. Additionally, Davis established a Bureau of Immigration to attract settlers and supported ambitious infrastructure projects like roads and rail improvements.

Many of these policies, while consistent with the 1869 constitution’s vision of activist government, sparked intense opposition from conservative Texans. Critics (mainly Democrats and former Confederates) accused Davis and the Radical Republicans of running an oppressive regime. The appointed judiciary and police were derided as tools of a “military despotism”, and the tax increases and rising state debt needed to fund schools and railroads were deeply resented in a state long hostile to taxation. The sight of Black policemen and Black legislators in the capitol (about 14 African Americans won election to the 12th Legislature) under the new constitution only further inflamed White Supremacist backlash.

Governor Davis’s firm enforcement of Black voting rights led to Democratic charges of election fraud and abuse of power. The 1869 constitution’s election provisions – especially the four-day county-seat voting rule – became a focal point for legal challenges after Democrats made gains. In 1873, the Texas Supreme Court (still packed with Davis appointees) voided an election result in what became known as the “Semicolon Case,” interpreting a punctuation mark in the election law to Davis’s benefit. Such controversies fed the narrative of Republican misrule.

By late 1873, when Davis ran for re-election, many white Texans were determined to end what they viewed as the “radical” regime. Davis lost the 1873 gubernatorial contest to Democrat Richard Coke amid heavy turnout by newly re-enfranchised ex-Confederates (Congress had removed remaining voting disqualifications) and systematic intimidation of Black voters in some areas. Governor Davis initially disputed the results, even appealing to President Grant for intervention. But when Grant refused to back him, Davis conceded defeat in January 1874, effectively marking the end of Republican Reconstruction governance in Texas.

The End of Reconstruction in Texas

Resistance to the Reconstruction constitution and to Governor Davis’s administration was widespread throughout this period, shaping both political and racial dynamics in Texas. White conservative Texans (Redeemer Democrats) saw the 1869 constitution as an illegitimate product of Northern coercion – a symbol of everything they hated about Reconstruction. This hostility manifested in both the ballot box and violent insurgency.

From the start, Democratic newspapers and leaders blasted the convention and constitution. They encouraged white voters to oppose ratification (though ultimately it passed) and later worked tirelessly to elect Democrats to the legislature and local offices. Once Democrats gained a foothold, they used every tool to undermine Reconstruction policies. For instance, the Democratically-inclined 13th Legislature (1873) refused to levy the school taxes mandated by the 1869 constitution, starving the public schools Davis had created. Democratic county officials often refused to cooperate with state police or election supervisors, frustrating enforcement of Black voting rights. By 1872–1873, as federal oversight waned, more ex-Confederates were voting and the Democratic Party was revitalized, committed to “redeeming” Texas from Republican rule.

Armed resistance also played role in ending Reconstruction. Secret societies like the Ku Klux Klan and local terror bands waged a campaign of intimidation against Black voters and white Republicans. During the late 1860s, Texas saw dozens of political murders; Freedmen’s Bureau records and military reports document frequent assassinations of Black leaders and Unionist officials. In one incident in 1868, a mob of ex-Confederates attacked a Republican gathering of Black voters and delegates in Millican, Texas, killing several people.

Governor Davis’s state police managed to curb some violence, but they themselves were vilified by conservatives as an occupying force. This climate of fear succeeded in suppressing Republican votes in many rural areas. By 1873, open armed resistance was less common than earlier, but the specter of violence loomed over elections, especially as federal troops had largely withdrawn.

The convergence of political mobilization and intimidation paid off for the Democrats in the 1873 elections that ousted Governor Davis. Thus began the process Texans called “Redemption” – the restoration of white Democratic control and the rollback of Reconstruction changes. With Davis gone and Governor Richard Coke installed in January 1874, the state swiftly moved to dismantle the 1869 constitutional system. The Democratic legislature immediately abolished the hated State Police and the militia, and reestablished local control of law enforcement. They also set in motion plans for a new constitutional convention to erase the last vestiges of Radical Republican rule.

The 1876 Constitution: Reversing Reconstruction Reforms

The Texas Constitutional Convention of 1875, composed almost entirely of Democrats (including six Black delegates, Republicans from districts with Black majorities), met with the explicit aim of replacing the 1869 constitution. Texas’s experience under Reconstruction heavily influenced the new charter they produced. The resulting Constitution of 1876—approved by voters in 1876—radically transformed Texas government again, this time in the opposite direction of 1869. Essentially, it codified a “Redeemer” backlash against centralized authority and activist government. Key reversals and differences included:

- Decentralization of Power: The 1876 Constitution stripped the governor of many powers that the 1869 document had granted. Governor’s terms were kept at four years, but now most executive officials became elected by the people (including the Attorney General and judges), sharply reducing gubernatorial appointment power. The legislature’s sessions and authority were curtailed as well, and local governments were empowered again. For example, all judges (from the Supreme Court to district courts) were to be chosen by election under the 1876 charter, returning control of the judiciary to voters at the local level. This was meant to prevent any future governor from dominating the courts as Davis had.

- Decentralization of Education: The new constitution also decentralized education, removing the mandate for appointed state school boards and giving local districts more say (while still segregating schools by race via statute shortly after).

- Reduced Government Scope and Spending: The 1876 framers were determined to prevent the “extravagance” they associated with Reconstruction. They placed tight limits on state taxes, debts, and expenditures. Salaries of public officers were slashed or capped, and the legislature was forbidden from incurring many kinds of debt. “Economy and efficiency” were the watchwords. In contrast to 1869’s proactive encouragement of internal improvements, the 1876 constitution made it difficult for the state to spend on infrastructure or subsidies, reflecting the agrarian small-government ethos of the Grange movement that influenced many delegates. The expansive social welfare vision of 1869 (public schools, immigration bureau, etc.) was dialed back to barebones or left to local initiative.

- State’s Rights and Fragmented Authority: Perhaps most tellingly, the 1876 Constitution backed away from the strong affirmation of U.S. supremacy that had been in the 1869 document, though nominally, federal law was still acknowledged as supreme.

- Retention of Basic Rights (with Caveats): One area the Redeemers did not fully reverse was Black male suffrage – but only because by 1876, the 15th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution forbade states from denying the vote based on race. The 1876 Texas Constitution formally maintained that no racial bar to voting existed. However, it introduced other mechanisms that would later suppress minority voting, such as a stringent poll tax (kept from the 1869 system ostensibly to fund schools) and complex local election procedures. In practice, within a few decades, Black Texans effectively lost meaningful voting power under the Jim Crow order, despite the letter of the 1876 law. On other civil rights, the 1876 charter notably did not guarantee integrated education or equality in public accommodations – those progressive ideas of the Radical era were discarded.

In short, the Constitution of 1876 was a complete repudiation of the 1869 Constitution’s philosophy. It embodied the victorious Democrats’ aims: limit government, lower taxes, decentralize power, and entrench White conservative rule. This 1876 constitution, heavily amended but still in force today, became the foundation of Texas governance going forward.

Legacy of the Reconstruction Era in Texas Governance

The brief period of Reconstruction rule and the constitutional whiplash from 1869 to 1876 left a lasting imprint on Texas. In the decades after 1876, Texas was governed under the ideals enshrined by the Redeemers, but the struggles of Reconstruction were not forgotten. Some enduring legacies include:

- A Skeptical View of Central Authority: The excesses (real or perceived) of Governor Davis’s administration cemented in Texas political culture a deep wariness of concentrated power in Austin or Washington. The 1876 constitution’s distrustful design – with its fragmented executive branch, biennial legislature, and cumbersome amendment process – ensured that no single faction could easily dominate. This structure survived into the modern era, and Texas governors remain relatively weak compared to those in other large states. Even today, Texans often favor local control and limited government, reflecting attitudes passed down from those who “broke the back” of Reconstruction centralization.

- A Constitution of Limits: The Texas Constitution of 1876 became one of the longest and most amended constitutions in the country, precisely because so many policy details (tax limits, debt ceilings, regulation of railroads, etc.) were locked into the document by the Redemption generation. By embedding constraints that were reactions to Reconstruction, the framers created a charter that has required constant amendment to adapt to new realities. This constitutional framework, however unwieldy, has persisted. Modern efforts to overhaul it (for instance, in 1974) have failed, leaving Texas with a patchwork but still recognizably 1876-based constitution. The spirit of 1876 – cautious, anti-authoritarian, and localist – continues to influence Texas governance.

- One-Party Dominance and Racial Order: Another legacy was the near century-long dominance of the Democratic Party in Texas that began with Reconstruction’s end. Branded as the party of “redeeming” Texas from carpetbaggers and Black rule, the Democrats became virtually unchallenged in state politics into the mid-20th century. After federal troops withdrew, white supremacy was rigorously enforced. Black Texans, though technically enfranchised, were steadily marginalized through Jim Crow laws, economic coercion, and violence. The progressive promises of the 1869 constitution – racial equality, public education for all, activist help for the needy – were largely rolled back, affecting Texas society for generations.

- Enduring Myths and Identities: The drama of Reconstruction also fed into the Texas identity. The narrative of heroic resistance to tyranny – with E. J. Davis cast as the villainous dictator – became a staple of Texas political lore in the late 19th and 20th centuries. The memory of being “under the bayonet” during Congressional Reconstruction ingrained a reflexive states-rights sentiment that Texan politicians consistently invoked in conflicts with Washington.

In conclusion, the saga of the 1869 Texas Constitution—its revolutionary expansions of rights and power, its rapid demise, and its replacement by the 1876 Constitution—encapsulates the turmoil of Reconstruction in Texas. Legally, it was a contest between a vision of multiracial democracy enforced by a strong state versus a vision of traditional local rule with minimal government. Politically, it was a battle between those who embraced change (often under federal prodding) and those who fiercely resisted it.

The victorious model of 1876 has proven durable; it still undergirds Texas government structure and reflects an ingrained skepticism of activist governance. Yet, the ideals briefly embodied in 1869 – equality before the law, education for all, and a powerful state safeguarding rights – would re-emerge in Texas history, albeit much later during the 1960s civil rights movement.

The Reconstruction era thus lives on in Texas’s long constitutional story: a reminder of how dramatically a state’s fundamental law can shift in response to broader social upheaval, and how those shifts can resonate for centuries.