Though largely forgotten today, Lanham was a leading statesman for 40 years and a hard-working governor at the dawn of the Progressive Era.

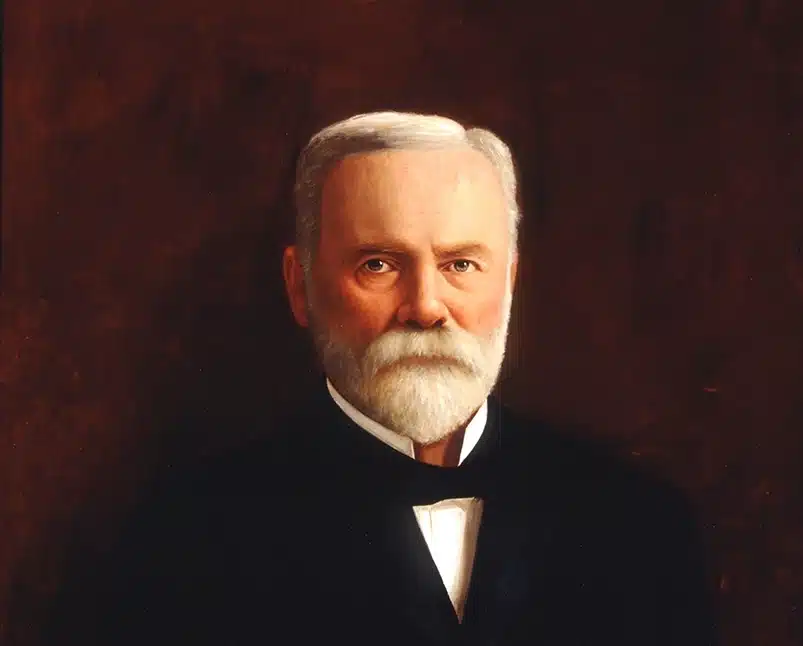

Samuel Willis Tucker Lanham (1846–1908) served as a U.S. congressman representing Texas and as the 23rd governor of Texas for two terms at the turn of the 20th century. A former teacher, frontier prosecutor, and soldier, Lanham earned a reputation as a skilled administrator and orator. Lanham governorship witnessed few dramatic crises or controversies, and his relatively uneventful years in office are often glossed over or ignored in textbooks or histories. Yet Lanham was one of the most experienced statesmen to hold the office of governor, who bridged the eras—and ideologies—between the post-Reconstruction Redeemer Democrats, and the Wilsonian Democrats of the Progressive Era.

Lanham’s entire tenure as governor fell within the presidency of Theodore Roosevelt, who is often described as a “Progressive” Republican (a term that had a different meaning than it does today). Despite the near total dominance of the Democratic Party in Texas at the time, Roosevelt was very popular in Texas and widely extolled in the press.

Though not a member of Roosevelt’s party, Lanham shared certain of Roosevelt’s goals, and he welcomed him during the president’s 1905 visit to Texas. At the time, both major political parties were in flux, and the president said during a speech at the Texas Capitol, “I think, Governor Lanham and Mr. Speaker and gentlemen, that the longer our experience in public office, the more we realize that at least 95 percent, if not more in importance, of the work by any public officer who is worth his salt, has nothing whatever to do with partisan politics. The things that concern us all as good citizens are infinitely larger than the matters concerning which we are divided one from the other along party lines.”1

Lanham’s administration focused on education, railroad regulation, fiscal stabilization, and the improvement of state institutions, including penitentiaries and universities. He was arguably Texas’s hardest working governor, spending long hours delving into administrative complexities, dealing with correspondence and legislative relations, and attending to petitioners.

To assist him, the governor recruited his son, Fritz G. Lanham, as private secretary; the heavy workload and long hours caused the young man to drop out of law school (he subsequently became a U.S. Congressman anyway). Toward the end of his tenure, Governor Lanham suffered declining health and depression. He found the many demands of the office to be taxing, and he died just over a year after leaving office. Before his death, Lanham said of the governorship:

“Office seekers, pardon seekers and concession seekers overwhelmed me—they broke my health—and when a man finds his health gone, his spirit is broken.”

Childhood and Civil War Service

Lanham was born on July 4, 1846, and reared on a farm in Spartanburg County, South Carolina. Though he had distinguished relatives and ancestors—an uncle was a judge in the George Supreme Court, for example—Lanham was the eldest of eight children and grew up in poverty. He received only haphazard education at the local “common school” (a precursor to public schools). The family did not own slaves.

As war fever swept the country in 1861, Lanham, though still a boy, decided to enlist as a private in the Confederate Army—a decision that cost him the remainder of his school years, and left him struggling, as an adult, to catch up in subjects like arithmetic. Lanham served from 1865 to 1869, from age 15 to 19, mostly in Virginia under Robert E. Lee.

At the end of the war, he returned to his father’s farm where his siblings, still school-aged, were being tutored by a young teacher named Sarah Beona Meng, who was just one year his senior. She became his tutor as well, as he tried to catch up with his schooling. The two fell in love and were married in 1866.

Move to Texas and Early Career

With much of the South in economic ruins following the Civil War, the newlyweds headed west together with nineteen other people. Upon arriving in Texas, their entire possessions consisted of a covered wagon, two horses, personal items, and $166 in savings.2

After a stay in Red River County, the couple settled in Weatherford, Parker County, in 1868, where they would remain for the rest of their lives, apart from stays in Austin and Washington, D.C. They lived in a two-room log cabin and set up a schoolroom in one room and lived in the other room, charging tuition of two to four dollars per month. The public school system in Texas at that stage was still patchwork, especially on the frontier, but enterprising teachers could still make a living as many settlers valued education enough to pay for a tutor or shared teacher for their children.

Despite missing years of schooling, Lanham was excellent in Latin and, according to his son Fritz, “could read Virgil’s Aeneid in the original text as readily as if it were printed in English.”3

In the meantime, Lanham studied law, and was admitted to the bar in Weatherford in 1869.4 Two years later, Lanham was appointed district attorney for the Thirteenth District of Texas. He served in that role until 1876, prosecuting crimes of all kinds, including, most famously, two Kiowa Indian chiefs involved in an attack on a wagon train.

Notably, Lanham received his appointment from the Reconstruction governor of Texas, Edmund J. Davis, a Republican, despite his Democratic Party affiliations and his years of service in the Confederate Army. The more precise political circumstances of the appointment are unclear, and the selection may have been based on merit or the shortage of other qualified lawyers in the remote judicial district.

Congressional Career

Having earned a reputation as an effective prosecutor of frontier crime, Lanham sought higher office. He served as a presidential elector in 1880 for the Democratic ticket and won a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives in 1882.

As a congressman, Lanham represented a vast but sparsely populated region of the Texas frontier. Known then as the “jumbo district,” it comprised 98 counties and was geographically the largest congressional district in the United States. His committee service reflected his interests and background, including Judiciary, Territories, Military Affairs, and Irrigation of Arid Lands. According to the Fort Worth Record:

“It was said of him that he secured an appropriation quicker than any man ever before in the nation’s congress, for he introduced a bill making an appropriation for some public work in El Paso, and the bill passed and became a law in four days from the time it was introduced. This was done in the early eighties.”5

Lanham left Congress voluntarily in 1890 and practiced law in Weatherford, before making an unsuccessful run for governor in 1894. At the time, the short-lived Populist Party was at its height, challenging Democratic dominance in Texas. Democratic Party leaders urged Lanham to reclaim his seat in congress, so he agreed, defeating Charles H. Jenkins in 1896.

From 1887–1889, Lanham chaired the Committee on Claims of the U.S. House of Representatives.6 He served until January 15, 1903, when he resigned to assume the office of governor.

Governor of Texas

Lanham was elected governor in 1902, while still serving in Congress, defeating Republican George W. Burkett and Populist candidate J. M. Mallett. He was re-elected in 1904 and served for a second term from January 1905 until January 1907. His administration coincided with an era of significant industrial expansion and population growth across Texas.

As governor, Lanham supported several key reforms:

- Railroad Regulation: Lanham advocated for increased oversight of railroad freight rates and conditions, responding to complaints from farmers and small merchants. During this first term, the legislature passed a law defining and prohibiting trusts and monopolies , which he considered the most important law passed that session.

- Tax and Fiscal Reform: He promoted equalization of property taxation and sought to increase state revenues to fund public services. The legislature imposed a franchise tax on corporations.

- Education: His administration supported public education and teacher training, including state normal schools and improvements in rural school funding.

- Child Labor Restrictions: Lanham signed legislation restricting child labor in certain industries, reflecting growing national attention to labor reform.

Despite these efforts, his administration faced challenges from rising corporate power, political factionalism, and the limits of gubernatorial authority in Texas’s constitutionally weak executive system.

Tensions with the Legislature

Texas was enjoying an era of relative stability when Lanham assumed office in 1903, especially compared to the tumultuous decades of Lanham’s youth. He later reflected,

“Many great questions of public policy had been settled and reduced to law anterior to [my] inauguration, and comparatively few measures of unusual importance and urgent necessity were being agitated. The State was remarkably quiet, the people were generally satisfied and prosperous, and the public mind was relatively undisturbed by serious contention. There was an absence of what is usually classed as ‘burning issues.’ So tranquil was the situation that among the introductory words of [my] first message to the Twenty-eighth Legislature, [I] took occasion to say: ‘It is not believed that a large amount of new legislation is needed (aside from platform demands). Too many laws—too much government—are not desirable. Only such matters as the actual conditions and public necessities call for should consume our time or absorb our attention. We should avoid any ill-advised experimentation.’”7

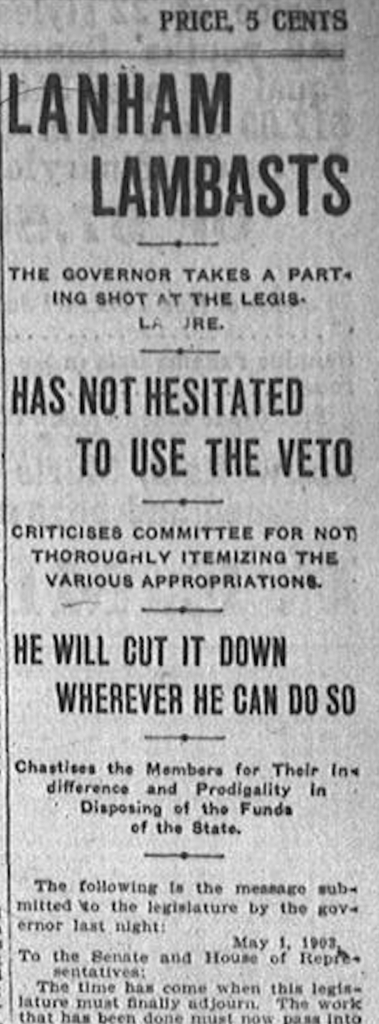

Despite his hopes for a tranquil governorship, Lanham soon clashed with the Texas Legislature, which had increased spending without raising taxes. This decision, coupled with an economic recession in 1903-1904, resulted in a deficit. Rather than downplay the problem or go along with lawmakers (who belonged to his party), Lanham urged them to raise taxes. When they failed to do so, he vetoed multiple line items from the appropriations bill.

Yet the state was still compelled to suspend payments to certain vendors in 1904. When the 29th legislature convened in 1905 at the start of Lanham’s second term, he again urged lawmakers to find new sources of revenue and raise the property tax rate to 25 cents. Ignoring the governor, lawmakers adjourned without doing so. He then called the legislature back into special session, stating, “The means to carry on the Government, to pay its debts and maintain its credit must be supplied. I reiterate the suggestions made to you at the regular session… With the appropriations already made and yet to follow, and the current expenses to be met, the end of the present year will find the State in arrears in a very large amount.”

The legislature met Lanham halfway, increasing the ad valorem rate to 20 cents for 1905 and 1906, and thereafter falling back to 16 and 2/3 cents. Despite this measure, the general revenue fund was twice exhausted in 1906 and cash payments were temporarily suspended.

Eventually, as government departments reined in spending and revenue improved, the deficit turned into a surplus. Lanham reported on leaving office, “Notwithstanding the difficulties and fiscal embarrassments with which we have been confronted, it is pleasing to know that the financial condition of the State is fairly satisfactory and, indeed, far better than the uninformed have supposed and than might have been expected under all the circumstances that have arisen.”8

Lanham pardoned approximately 400 convicts during his two terms, commuted five death sentences, and remitted a number of fines and penalties in misdemeanor cases.

He vetoed several bills, in addition to the spending items previously mentioned. In 1905, the Legislature passed a law that would have made the state responsible for the upkeep of a new Confederate Women’s Home (for widows and relatives of veterans), which the United Daughters of the Confederacy had established and hitherto operated.

Although Lanham supported the existing practice of funding pensions of aging ex-Confederate soldiers, and funding a home for the disabled and indigent veterans, he believed that supporting their relatives would be unconstitutional.9

Retirement and Death

After completing his second term, Lanham declined to run for a third and retired from public life. He returned to Weatherford, where he was known to have enjoyed daily drives through the small town where he had made his home for four decades. He received an honorary doctorate from Baylor University, and was appointed as a University of Texas regent.

Lanham’s wife died on July 3, 1908, and Lanham himself died within weeks of her, at the age of 62, on July 29, 1908. The Fort Worth Record reported, “Mrs. Lanham died very suddenly and at the time her bereaved husband expressed a desire to follow her. He had been in ill health for several years, but from the time his wife was taken off he sank slowly but surely to the end tonight.”10

Legacy

S. W. T. Lanham’s governorship is generally viewed as a transitional period in Texas political history. He was one of the last Texas governors born outside the state, one of a long line of immigrants from the Old South. He was the last former Confederate soldier elected as governor, and one of the first governors to serve after the end of the “Wild West” era.

The coming years would be known as the “Progressive Era,” as factions within both the Democratic and Republican parties embraced a variety of economic, social, and political changes, including tax and tariff reforms, new anti-trust and banking laws, women’s suffrage, direct election of U.S. senators, labor laws, and more. Lanham’s successor Thomas M. Campbell is sometimes described as the first Progressive Era governor of Texas, yet Lanham was a transitional figure in his own right, whose tenure has gone largely overlooked.

His subsequent obscurity may owe something to his own personality as governor. Lanham did not idealize the governorship or use it to craft a public persona. He approached the office as a burden to be managed, not a stage to be occupied, and he stepped down without fanfare.

Lanham’s son, Fritz G. Lanham, later served in the U.S. House of Representatives. While in his 20s, Fritz had served as secretary to his father throughout his governorship. Due to the heavy workload, he dropped out of the University of Texas at Austin school, but still went on to a distinguished career in law. The Lanham Act, the primary statute governing trademark law in the United States, is named for him.

Sources Cited

- “President Roosevelt in Austin,” Austin Statesman, April 7, 1905, pg. 1. ↩︎

- Joe Cleveland, “Fritz Garland Lanham—Father of American Trademark Protection,” Journal of Supreme Court History 48, no. 3 (Summer 2023): pg. 44. ↩︎

- Ibid., pg. 44. ↩︎

- It was common and legally permissible to study law informally and then begin practicing without a formal law school education. Many aspiring lawyers apprenticed under a practicing attorney or judge and bar admissions were overseen by district judges. This was the dominant path to becoming a lawyer throughout most of the 19th century, especially in areas without access to formal legal education. ↩︎

- Fort Worth Record, July 30, 1908, pg. 3. ↩︎

- This committee dealt with thousands of petitioners seeking payment from the federal government for various grievances, making it one of the busiest committees in Congress. It was an important avenue for redress before modern administrative and judicial remedies were available. The committee did not deal with policy legislation. Instead, it focused on private bills—specific acts granting relief to individual petitioners. Lanham’s appointment to chair this committee suggests that his peers in Congress viewed him as both judicious and attentive to details. ↩︎

- Journal of the Texas House of Representatives, January 10, 1907, pg. 20. ↩︎

- Farewell Message, pg 24-25 ↩︎

- After Lanham’s veto, the United Daughters of the Confederacy continued operating the home as a private charity, until Texas voters approved a constitutional amendment in 1911 deeding it to the state. ↩︎

- Fort Worth Record, July 30, 1908, pg. 3 ↩︎