This article is part of Texapedia’s curated primary source collection, which makes accessible both famous and forgotten historical records. Each source is presented with historical context and manuscript information. This collection is freely available for classroom use, research, and general public interest.

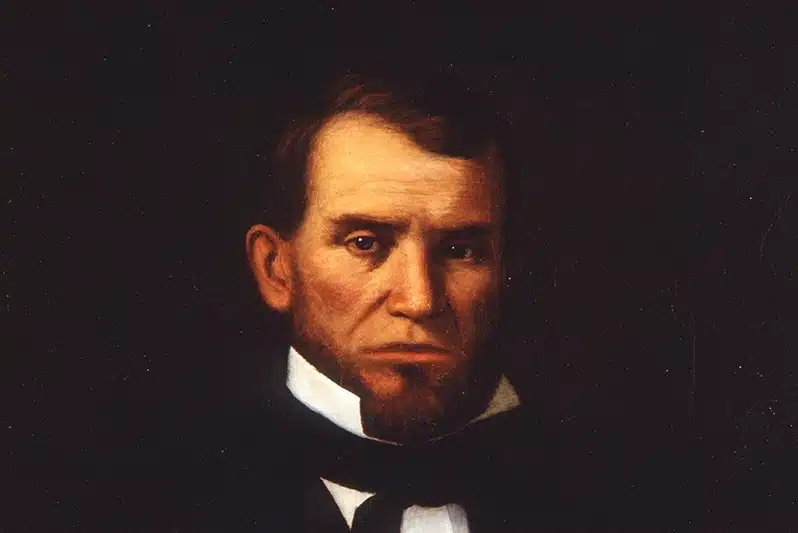

Before Christmas of 1859, Governor Hardin R. Runnels delivered a farewell address at the Texas Capitol, warning of impending war and issuing a call to arms in defense of slavery. The speech took place little more than a year before the first fighting of the U.S. Civil War, and just two months after the raid at Harper’s Ferry by radical abolitionist John Brown.

Brown and 21 armed followers had attacked a federal arsenal in Virginia (present-day West Virginia) in October 1859, hoping to seize weapons and initiate a slave revolt in Southern states. Though the attack failed—Brown and most of his followers were killed or captured—it stoked fears throughout the slaveholding South and accelerated the development of a militia system that would become the nucleus of the Confederate States Army in the Civil War.

The raid also convinced Southern leaders of the radicalism of Northern politicians and their willingness to use any means to destroy slavery in the South. This ignored the views of anti-slavery moderates like Abraham Lincoln, who did not believe in using violence to end slavery in the Southern states. Even Northern newspapers referred to the raid at Harper’s Ferry as an “insurrection,” “rebellion,” or “treason.” Yet many Southern politicians wanted secession anyway, viewing it as the best way to secure the plantation economy of the South.

In this speech, Governor Runnels typifies the response of Southern politicians who exploited fears over the Harper’s Ferry raid to agitate for armed mobilization and, eventually, armed conflict. Runnels called for “the organization of a militia in view of the impending sectional difficulties as a measure of public defense.” Militias historically had played an important role in American history, including the Texas Revolution, but they varied considerably in their professionalism, organization, armament, and permanence.

Runnels and other Texan leaders envisioned a militia that, though organized at the community level, received support and an overall command structure from the state. From this point onward, preparations for war accelerated throughout Texas and the South generally. The development of state militias in 1859-1861 gave the Confederate states an advantage in early battles against the Union, notwithstanding the North’s larger population and industrial base, which eventually contributed to the Union victory in the Civil War.

Although Runnels did not mention John Brown by name in this speech, he described in general terms “a deep unchangeable determination… in the Northern States to assail our dearest political rights, and if possible destroy our domestic institutions.”

He added, “This determination has its foundation in a difference in the manners, feelings and opinions of the northern people upon the subject of negro slavery. They believe it to be a moral, social and political evil… in the South, the great mass of the people entertain opinions entirely opposite in their character, which are equally immovable and equally amalgamated with our religion and morality.”

This speech contrasts sharply with the inauguration address of Sam Houston, delivered on the same day in December 1859. Houston, the former president of the Republic of Texas, had lost the governor’s race to Runnels in 1857, but won it two years later, ousting Runnels. During Houston’s brief time as governor (he was eventually forced to resign), he argued to keep Texas in the Union, participating in the debate over secession against the “fire eaters” like Runnels, who favored secession at any cost.

After leaving office, Runnels participated in the 1861 Secession Convention and the 1866 Constitutional convention, where he earned a reputation as an “aggressive secessionist” or “irreconcilable.” Runnels owned a plantation in Bowie County and 39 slaves.

The Outgoing Address of Governor Hardin Runnels

December 21, 1859

Gentlemen of the Legislature and fellow-citizens:

This vast concourse has assembled to-day to witness one of those interesting periodical events which mark the history, progress and development of a free constitutional government, to witness the transfer of honor and authority from those who have been entrusted with the difficult and perplexing cares of State, to the hands of others, who, by election of the people, have been chosen to assume them.

It having been my fortune to hold the position which I am now about to surrender, for the past two years, custom as well as a proper regard for the occasion has seemed to require that I should add my presence and participate in the ceremonies that are to commemorate it. In performing this task, let no one be surprised at the difficulty I find in arriving at that which shall at the same time be appropriate and expressive of my own sentiments, nor let it be supposed that this difficulty and embarrassment arises from any feeling of reluctance at the surrender of a position environed with difficulties, which it has required so enlarged a sentiment of self-sacrifice and so much firmness and determination of purpose, faithfully to encounter.

There are those within the sound of my voice who know that the act of to-day would have been voluntary on my part, could I have been permitted the free exercise of my own inclinations; but had they even been different, and the office again earnestly desired, I should regard my position in defeat far more fortunate and honorable than to have succeeded at a price of principle and a surrender of the independence of thought, or, by swerving one iota from that disinterestedness of action by which he who has imposed on him high moral and constitutional duties should alone be governed.

It is not my intention to weary the public patience with a recital of my long connexion with our public affairs, nor shall I stoop to a vindication of its history from the misrepresentations with which it has been assailed. The time and occasion are not propitious. The purpose of the hour is to listen to the enunciation of principle and policy from those who are to take—not those who are about to yield position.

My own is already part and parcel of the history of the country, and it is for those who may seek truth for their guidance to examine it and judge for themselves. As a Representative of the people, as the presiding officer of either branch of the Legislature, or as the Executive of the State, I have faltered in the performance of no duty, changed no opinion, abandoned no position, advanced no new theory, but consistently adhered to the same principles of State and federal policy from the beginning of my career to the present time; striving only for the present and future welfare and safety of my State and country.

It has been well and truly said that “censure is the tax a man pays the public for being eminent,” and without presuming upon this myself, if I could close my eyes to the truth, that the recent change of popular sentiment, is more to be attributed to the name and fame of the aged and eminent chieftain who sits before you, than to the course of a few licentious presses and politicians who in the heat of partisan strife have forgotten or disregarded the proprieties and amenities of life, I should then regard that change as truly suggestive of serious reflection to those who may hereafter seek to tread the thorny path of political life in Texas.

Two years ago on taking the oath of office I recommended the organization of a militia in view of the impending sectional difficulties as a measure of public defense, as a necessary measure of public defense only. It was not then favorably acted on by the Legislature, but subsequent events have fully justified the recommendation.

It is now clearly demonstrated by the history of the past five years that a deep unchangeable determination exists in the Northern States to assail our dearest political rights, and if possible destroy our domestic institutions. This determination has its foundation in a difference in the manners, feelings and opinions of the northern people upon the subject of negro slavery. They believe it to be a moral, social and political evil. This belief strengthened into a conviction has been incorporated with and now constitutes the soul of their religion and the mainspring of their morality.

In the South, the great mass of the people entertain opinions entirely opposite in their character, which are equally immovable and equally amalgamated with our religion and morality. We therefore occupy the singular and anomalous position of two people differing in almost everything calculated to promote peace, happiness and fraternity, and yet in many respects living under the same government.

One of these people is actuated by a spirit of aggression; the other standing upon the ramparts of the constitution, is acting upon the defensive, and asking only to be let alone. It is unnecessary to recapitulate facts to substantiate these truths, nor that a wide spread conviction exists that we are approaching a terrible crisis, and that we being forewarned we should be also forearmed.

The history of the world affords no example of two people so divided long remaining under a common government, of their own voluntary accord. The fathers of ours foreseeing a change of the opinions and sentiments of its different people, attempted by leaving this and other questions of domestic policy to the State government as much as possible, to avoid if practicable, future cause of disruption, and by restricting the federal government to the powers delegated by the constitution, place it beyond the power of any one section to interfere with the peculiar interest and institutions of another.

The binding efficacy of these restrictions from every indication is now soon to be tested, and a question to be determined is, whether Texas will remain indifferent to the consequences while those with whom she should be united by every tie of blood and interest, are animated with but one sentiment in regard to the common danger. Preparation will not hasten the coming of events, if come they must, while if it does not prevent, it may avert the consequences of the threatening storm. The time has surely arrived when the South should look to her defences.

I have now, perhaps, exceeded the limits prescribed for such an occasion; yet I can not conclude without a word of farewell to those with whom I have been associated; who are bound to me by the strongest ties of sympathy, and that friendship which results from common labors and common motives.

I honor the magnanimity which rises above the mere considerations of party. The rancor of its hostilities is more than counterbalanced by the spirit of truth and justice evinced by it, and above all, the remembrance of that charity blended with so many evidences of kindness and appreciation from fair hands, which has been so generously bestowed during my sojourn at the Capital, will be carried with me to my distant home, and deeply treasured in the well of memory until life’s last pulsation shall cease.

Manuscript Information

This speech was published in the Journal of the Texas House of Representatives, printed at Austin in 1860 by John Marshall & Co., state printers.

Runnels delivered the speech at a joint session of the legislature. At his request, the lawmakers assembled in front of the Texas Capitol, rather than the House chamber where governors typically deliver their farewell addresses. The speech was Runnels’ official farewell address after a two-year term of office.