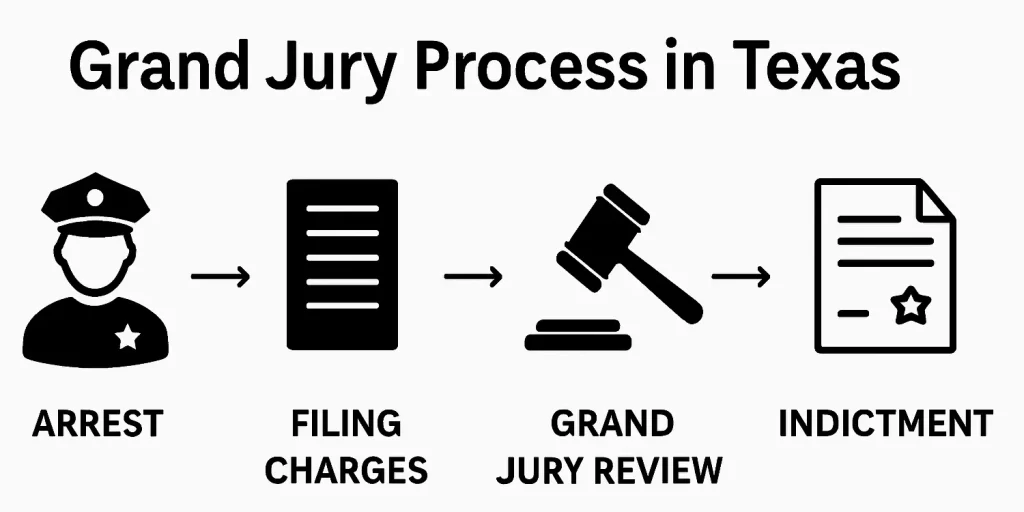

In Texas, the criminal process begins well before a trial. Once law enforcement officers make an arrest or complete an investigation, the case moves into the charging phase. Understanding how charges are filed and how indictments work is crucial to grasping the broader criminal justice system in the state. These pre-trial steps — from evidence review to grand jury deliberations — determine whether a person faces formal prosecution and set the tone for everything that follows, including plea negotiations, trial preparation, and sentencing outcomes.

Filing of Charges

After an arrest or investigation, the next step is for prosecutors to decide whether to file charges. In Texas, a prosecutor (usually a district attorney or a county attorney) reviews evidence provided by law enforcement. The prosecutor has broad discretion and can choose to:

- File criminal charges

- Decline to pursue charges

- Refer the case for further investigation

For misdemeanors, prosecutors can file charges directly by submitting an information, which is a formal written accusation. For felonies, however, a grand jury must usually approve the charges through an indictment.

It is important to note that not every arrest leads to the filing of charges. In some cases, there may be insufficient evidence to support a prosecution, or pursuing charges might not serve the public interest. In these instances, the case may be “no billed,” meaning it does not advance to formal prosecution. Defendants benefit from this early screening, avoiding the stigma and consequences of a full criminal case without adequate foundation.

The Grand Jury Process

For felony charges, Texas law requires review by a grand jury. A grand jury is a group of 12 citizens who meet in private to evaluate evidence presented by prosecutors. Unlike a trial jury, the grand jury does not decide guilt or innocence. Instead, they determine whether there is “probable cause” to believe a crime was committed and the accused person is responsible.

The grand jury process is conducted in secret, a measure intended to protect the reputations of individuals under investigation and to encourage open discussion among jurors. Witnesses, including victims or law enforcement officers, may be called to testify, but defense attorneys and the accused typically do not participate. The standard of proof is relatively low compared to trial — it is enough for the jury to find probable cause, rather than proof beyond a reasonable doubt.

If the grand jury concludes that probable cause exists, it issues a “true bill,” leading to a formal indictment. If it finds that probable cause is lacking, it issues a “no bill,” and the case is usually dismissed unless new, compelling evidence emerges later.

Indictments

An indictment is a formal written statement charging a person with a felony offense. It is drafted by the prosecutor and approved by the grand jury. An indictment includes basic information:

- The accused’s name

- The alleged offense

- A brief description of the criminal act

- The date and county where the offense occurred

Indictments do not include detailed accounts of evidence or witness testimony; their purpose is to officially initiate felony-level court proceedings. Once indicted, a person becomes a defendant in a criminal case and must appear before the court to respond to the charges.

In rare cases, a felony prosecution may proceed without a grand jury indictment if the defendant voluntarily waives the right to grand jury review, usually as part of a negotiated plea bargain. This process allows for a felony charge to be “filed by information” instead of indictment, streamlining resolution when both sides agree.

Arraignment

After charges are filed or an indictment is issued, the defendant must appear in court for an arraignment. The arraignment is the defendant’s first formal court appearance tied to the criminal charges. It serves several important purposes:

- The charges are read aloud in court (unless waived by the defendant)

- The defendant is advised of their rights

- The defendant enters a plea: guilty, not guilty, or no contest

If the defendant pleads not guilty, the case proceeds to pretrial hearings and, eventually, trial. Pleading guilty or no contest may lead directly to sentencing or further plea negotiations.

In Texas, arraignment is typically a short hearing, but it marks the official start of active court proceedings.

Modification or Dismissal of Charges

Once charges are filed, the path to trial is not always straightforward. Several outcomes are possible before a trial jury is ever seated:

- Amendment of Charges: Prosecutors can amend the charging document to add new charges or reduce the severity of existing charges based on newly discovered evidence or legal strategy.

- Dismissal of Charges: Charges can be dismissed entirely if evidence is insufficient, procedural errors have compromised the case, or other legal defects are found. In some cases, successful defense motions (such as motions to suppress key evidence) can lead to dismissals.

- Refiling of Charges: If a case is dismissed “without prejudice,” prosecutors retain the right to refile charges at a later time if new facts emerge or initial defects are corrected.

In Texas, the law tries to balance the power of prosecutors with protections for people accused of crimes. It aims to ensure that charges must be backed by adequate evidence. It also gives defendants a chance to challenge the case early. What happens before trial — like motions and hearings — can shape the final outcome just as much as the trial itself.

This article is provided for general informational and educational purposes only and does not constitute legal advice. The laws and procedures discussed herein reflect Texas statutes and legal norms as of the time of writing and may be subject to change. Individuals facing arrest or criminal charges should consult a licensed attorney for guidance specific to their situation. Texapedia is a privately maintained encyclopedia and does not provide legal representation or services.