The civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s brought sweeping legal and social change. In Texas, Blacks and Mexican Americans led the fight for equal rights amid deep resistance.

For decades prior, segregation had been upheld by state law and local ordinances—enforced through separate schools, Whites-only primaries, segregated public facilities, housing discrimination, and voter suppression tactics. Mexican Americans were often categorized as “white” on paper but excluded in practice, especially in public schools and jury service.

These systems were not simply cultural norms—they were codified in Texas law and reinforced through official policy at every level of government.

The timeline traces key legal and political developments in Texas and the nation, showing how civil rights struggles played out at both state and federal levels.

1944 – Smith v. Allwright

The U.S. Supreme Court struck down Texas’s Whites-only primary system, ruling that political parties are state actors when conducting elections and cannot exclude voters based on race. For decades, Texas Democrats had used both state law and party rules to bar Black citizens from voting in primary elections—effectively denying them any real say in state politics, since the Democratic primary was the decisive contest in one-party Texas.

‘Earlier challenges to these practices had failed when courts treated political parties as private organizations. But in Smith, the Court reversed course, recognizing primaries as an integral part of the public election process. The decision dismantled one of the most powerful tools of Black voter suppression in Texas and led to a surge in Black voter registration, particularly in urban counties like Harris, Dallas, and Bexar.

1948 – Dixiecrat Revolt

At the 1948 Democratic National Convention, Southern Democrats—including many from Texas—walked out in protest of the party’s new civil rights platform, which called for anti-lynching laws, voting rights protections, and desegregation.

In response, they formed the States’ Rights Democratic Party, or “Dixiecrats,” and nominated South Carolina Governor Strom Thurmond for president. The revolt marked the beginning of a long-term political realignment, as civil rights increasingly divided the national parties and reshaped the loyalties of White Southern voters.

1950 – Sweatt v. Painter

Heman Marion Sweatt, a Black postal worker from Houston, applied to the University of Texas School of Law in 1946 but was denied admission solely because of his race. Backed by the NAACP and represented by Thurgood Marshall, Sweatt filed suit, challenging the state’s attempt to sidestep integration by hastily creating a separate law school for Black students in Houston.

The U.S. Supreme Court unanimously ruled that the new school—though superficially “equal”—was inferior in faculty, reputation, alumni network, and access to the state legislature and courts. The Court held that segregation in professional and graduate education violated the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment.

The decision marked a turning point: it weakened the legal foundation of “separate but equal” and laid crucial groundwork for Brown v. Board of Education four years later. Sweatt was eventually admitted to UT Law but withdrew before completing his degree, due in part to health issues and the emotional toll of the long legal fight. Nevertheless, the case opened the door for other Black students to enroll at the University of Texas and other flagship institutions across the South—making Sweatt a central figure in the legal dismantling of Jim Crow education.

1954 – Brown v. Board of Education

The U.S. Supreme Court declared racial segregation in public schools unconstitutional, overturning Plessy v. Ferguson and striking at the heart of Jim Crow education. In Texas, school districts responded with tokenism, evasion, and legal delays. Many districts implemented so-called “freedom of choice” plans or claimed compliance while maintaining separate and unequal facilities. State officials, including the attorney general and local boards, often resisted integration outright or adopted policies to minimize its practical impact.

1955 – Murder of Emmett Till

Emmett Till, a 14-year-old Black boy from Chicago, was murdered while visiting relatives in Mississippi after allegedly whistling at a White woman. He was abducted, tortured, and shot by two men who later confessed in a national magazine after being acquitted by an all-white jury. Though not a Texas event, the killing deeply resonated in Black communities across the state and intensified NAACP activism. The open-casket funeral and widely circulated images of Till’s mutilated body shocked the nation and inspired many young African Americans—including future Texas leaders—to join the growing civil rights movement.

1956 – Texas Legislature Passes Interposition Resolution

In defiance of Brown v. Board of Education, Texas passed a resolution asserting the right to “interpose” state authority against federal court rulings. Though symbolic, it signaled open defiance of federal civil rights enforcement and echoed states’ rights rhetoric dating back to the Confederacy. This episode reflected a broader pattern of legal posturing in Texas history—resurfacing in later debates over federal power and even modern secessionist sentiment.

1957 – Civil Rights Act of 1957

This landmark federal law banned segregation in places open to the public, such as hotels, restaurants, and theaters, and made it illegal to discriminate in hiring or education. It also gave the federal government new powers to enforce desegregation in schools and public services. In Texas, many businesses and school districts resisted these changes, especially outside major cities. Progress often came only after lawsuits or the threat of losing federal funding, with civil rights groups pushing hard to hold institutions accountable.

1956–1965 – Klan Resurgence

In response to desegregation rulings and federal civil rights laws, Ku Klux Klan chapters reemerged across Texas. Cross burnings, threats against civil rights workers, and racial violence occurred in cities like Dallas, Houston, and Longview. These acts of intimidation were often ignored or enabled by local law enforcement.

1959 – Mansfield School Desegregation Crisis

Mansfield ISD’s refusal to integrate was a defining example of Texas’s resistance to federal desegregation mandates. When a federal court ordered the district to admit Black students to Mansfield High School, local officials and White residents physically blocked entry, hanging effigies and threatening violence.

Rather than enforce the order, Governor Allan Shivers sent state troopers to uphold the segregationist position, setting a precedent of state-sanctioned defiance that delayed integration in many Texas districts for years.

1960 – TSU Students Launch Sit-Ins in Houston

Modeled on Greensboro, Black students from Texas Southern University protested segregated lunch counters in downtown Houston, facing arrest and public backlash.

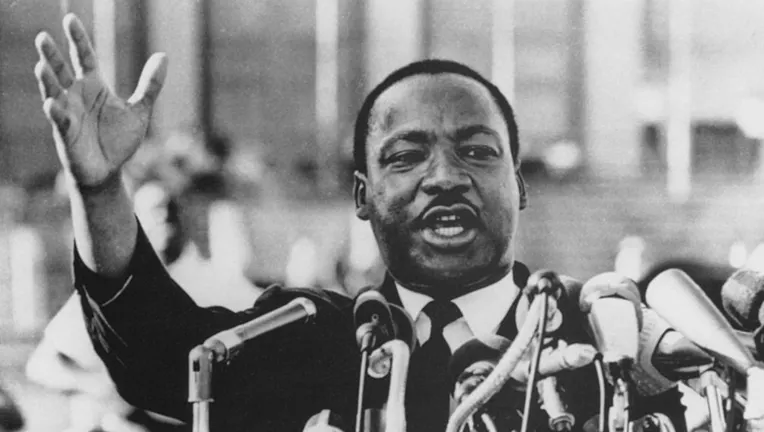

January 1963 – MLK Speech in Dallas

Martin Luther King spoke to over 2,500 attendees at the Music Hall in Fair Park, Dallas. Despite facing bomb threats and protests from segregationists, he delivered a message centered on love and nonviolent resistance.This event galvanized local civil rights activism and highlighted the challenges faced by the movement in Texas.

August 1963 – MLK’s “I Have a Dream” Speech

More than 250,000 Americans gathered at the Lincoln Memorial for the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his iconic “I Have a Dream” speech, calling for an end to racism and for civil and economic rights. Though a national event, the march inspired activists in Texas and reinforced the urgency of civil rights organizing in the South.

November 1963 – Kennedy Meets Latino Leaders in Houston

Just one day before his assassination, President John F. Kennedy addressed a gathering of Mexican American civil rights advocates at the Rice Hotel in Houston. It was a historic gesture of recognition, as Kennedy acknowledged the political power and civic importance of Latino communities—many of whom had backed his election in 1960. The visit symbolized a growing national awareness of Latino civil rights as part of the broader movement.

November 1963 – Assassination of President Kennedy

President John F. Kennedy was assassinated during a motorcade in Dallas, Texas. At the time of his death, Kennedy had recently proposed sweeping civil rights legislation, marking a shift toward more active federal support for racial equality. In the aftermath, President Lyndon B. Johnson invoked Kennedy’s memory to rally support for the bill, urging Congress to act “as a memorial to President Kennedy.” The strategy succeeded: the Civil Rights Act of 1964 became law the following summer, transforming the legal and political landscape of the South—including Texas.

1964 – Landmark Civil Rights Act bans segregated spaces

This landmark federal law banned segregation in places open to the public, such as hotels, restaurants, and theaters, and made it illegal to discriminate in hiring or education. It also gave the federal government new powers to enforce desegregation in schools and public services.

In Texas, many businesses and school districts resisted these changes, especially outside major cities. Progress often came only after lawsuits or the threat of losing federal funding, with civil rights groups pushing hard to hold institutions accountable.

1965 – Voting Rights Act / Edcouch-Elsa Student Walkout

The federal Voting Rights Act of 1965 banned discriminatory practices such as literacy tests and empowered federal oversight of voter registration in areas with a history of suppression. In Texas, the law opened the door for increased political participation among Black and Mexican American voters—especially in South Texas, where exclusion from juries, ballots, and city halls had long been common.

That same year, Mexican American high school students in Edcouch-Elsa, a small town in the Rio Grande Valley, staged a walkout to protest unequal treatment, a Eurocentric curriculum, and discriminatory discipline. When school officials responded by expelling the striking students, the case reached federal court—and the students won reinstatement. The walkout became one of the earliest large-scale acts of Chicano student protest in Texas and helped ignite a broader wave of youth activism across the state.

March 1966 – MLK Address in Dallas

Martin Luther King spoke to a standing-room-only audience at Southern Methodist University’s McFarlin Auditorium in Dallas, discussing the ongoing struggle for racial equality and justice. His speech emphasized the necessity of continued activism and the role of young people in driving social change. This visit further solidified his influence on Texas’s civil rights landscape.

November 1966 – Barbara Jordan Elected to Texas Senate

Barbara Jordan’s election broke barriers in southern politics. A gifted orator and constitutional scholar, she became a nationally respected figure in civil rights and lawmaking.

1967 – Houston Police Kill Carl Hampton

Leader of the People’s Party II (Black Panther-affiliated), Hampton was shot and killed by Houston police after a standoff. His death sparked local outrage and protest over racialized policing.

March 1967 – Formation of MAYO

In 1967, the Mexican American Youth Organization (MAYO) was founded in San Antonio, Texas, by five young Chicano activists known as “Los Cinco.” MAYO became a significant force in the Chicano movement and was involved in voter registration drives, school walkouts, and the formation of the Raza Unida Party, playing a crucial role in increasing political representation for Mexican Americans in Texas

April 4, 1968 – Assassination of MLK

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in Memphis, Tennessee, sparking grief, outrage, and protests in cities across the United States. His death marked a turning point in the civil rights movement, galvanizing both mourning and renewed urgency. In Texas, Black communities held memorials and protests, while civil rights leaders used the moment to push for legislative action long delayed by political resistance.

April 11, 1968 – Fair Housing Act Passed

Just days after Dr. King’s assassination, Congress passed the Fair Housing Act as Title VIII of the Civil Rights Act of 1968. The law prohibited discrimination in the sale, rental, and financing of housing based on race, religion, or national origin. Although widely hailed as a civil rights milestone, enforcement in Texas cities like Dallas and Houston was weak, and residential segregation persisted for decades. The Act marked the last major legislative victory of the civil rights era.

April 6, 1968 – Crystal City Takeover

In one of the most significant political victories of the Chicano civil rights movement, Mexican American candidates backed by the Mexican American Youth Organization (MAYO) and the Political Association of Spanish-Speaking Organizations (PASO) won control of the Crystal City school board and city council in the municipal elections held on April 6, 1968. Located in South Texas, Crystal City had a majority-Mexican American population but had long been dominated by White political and economic elites.

Chicano activists organized an intensive grassroots campaign focused on voter registration, bilingual education, fair employment, and local representation. Their sweeping electoral victory made Crystal City one of the first municipalities in the United States to be governed primarily by Mexican Americans. It also laid the groundwork for the creation of the Raza Unida Party two years later, which sought broader political power for Chicanos across Texas and the Southwest.

July 1970 – United States v. Texas

The U.S. Department of Justice filed a federal lawsuit accusing the Texas Education Agency (TEA) of systematically failing to enforce desegregation in hundreds of school districts across the state. Though Brown v. Board of Education had outlawed school segregation in 1954, Texas authorities had long allowed de facto segregation to persist—especially in rural and majority-minority districts—by manipulating attendance zones, delaying integration plans, and classifying Mexican American students as “White” to avoid compliance.

The federal lawsuit charged that the TEA had abdicated its legal responsibility to enforce desegregation and instead enabled ongoing segregation. In response, federal courts issued broad orders requiring the TEA to actively oversee integration efforts, including mandatory busing, redistricting, and compliance monitoring.

The case marked a turning point in Texas education policy, forcing state officials to take a more direct role in dismantling dual school systems and setting off a wave of local resistance and litigation.

1970 – Uvalde School Walkout

In April 1970, over 500 Mexican American students in Uvalde, Texas, staged a walkout to protest the school board’s decision not to renew the contract of a beloved Mexican American teacher, Josué “George” Garza. The protest highlighted broader issues of discrimination and lack of representation in the school system. The walkout lasted six weeks and became one of the longest school walkouts during the Chicano Movement, drawing attention to educational inequalities faced by Mexican American communities.

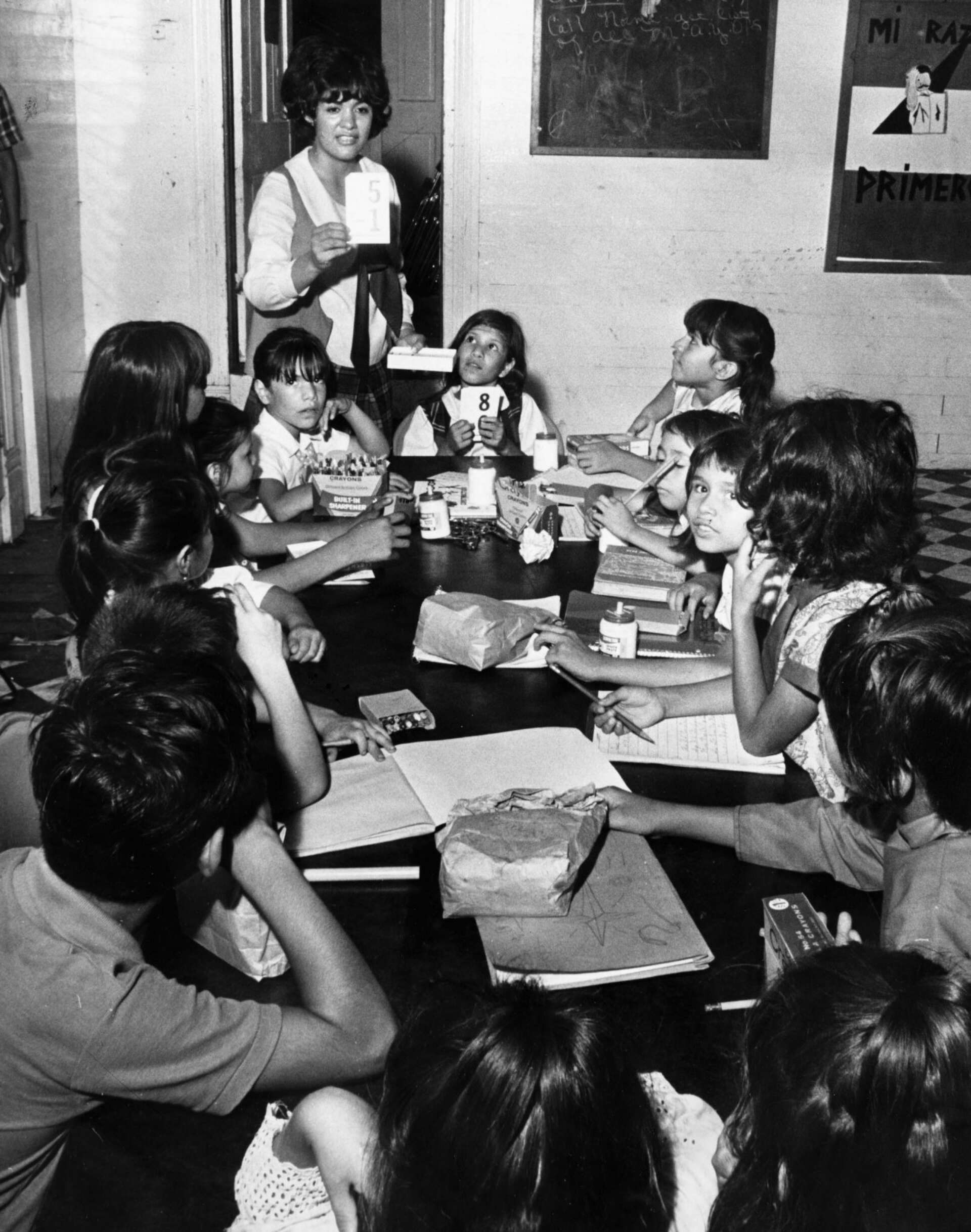

1970–1972 – Houston Huelga Schools

In response to the Houston Independent School District’s failure to adequately desegregate schools and address the needs of Mexican American students, the Mexican-American Education Council (MAEC) organized boycotts and established “huelga” (strike) schools between 1970 and 1972. These alternative schools provided culturally relevant education and became a form of protest against educational inequities. The movement pressured the school district to implement changes, including bilingual education programs and more inclusive curricula.

1973 – Killing of Santos Rodriguez

On July 24, 1973, 12-year-old Santos Rodriguez was fatally shot by a Dallas police officer during an interrogation over a minor theft. The incident sparked widespread outrage and protests within the Mexican American community, leading to increased activism against police brutality. The tragedy became a rallying point for Chicano civil rights advocates in Texas and beyond.

1973 – San Antonio ISD v. Rodriguez

In a 5–4 decision, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that education is not a fundamental right under the U.S. Constitution and upheld Texas’s school funding system based on local property taxes. The case, brought by families in San Antonio’s Edgewood neighborhood, challenged stark funding disparities between poor and wealthy districts. The decision was a major setback for equity advocates—but years later, similar arguments prevailed under the Texas Constitution in the landmark Edgewood v. Kirby case.

1975 – Voting Rights Act Amendments

On the tenth anniversary of the original Voting Rights Act, Congress passed the amendments to extend and broaden its protections—this time focusing on the rights of language minority groups. The amendments prohibited voting discrimination against citizens who spoke languages other than English and required jurisdictions with large populations of Spanish, Asian, Native American, or Alaskan Native voters to provide bilingual voting materials.

The changes helped boost voter participation among Latinos in Texas and reinforced the federal government’s role in overseeing election procedures across the state. Many Texas jurisdictions—including urban counties like Bexar, El Paso, and Hidalgo—were placed under continued federal review for compliance.

1978 – Regents of the University of California v. Bakke

In a divided decision, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that race could be considered as one factor in college admissions to promote diversity, but struck down the use of fixed racial quotas as unconstitutional under the Equal Protection Clause. The Bakke decision upheld the general principle of affirmative action while placing limits on its implementation. It had ripple effects on public university admissions across the country, including in Texas, where institutions began reevaluating race-conscious policies in light of the ruling.

Though Bakke shaped affirmative action policies for decades, it was ultimately overturned in 2023 when the Supreme Court ruled in Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard that race-conscious admissions policies violated the Constitution, effectively ending affirmative action in college admissions nationwide—including at Texas universities.

1981 – Edgewood School Finance Case

Plaintiffs argued that Texas’s reliance on property taxes created unconstitutional inequalities. After a long legal battle, the state adopted funding redistribution known as “Robin Hood.”

1980 – Juneteenth Becomes Official Holiday

Though celebrated since 1865, Juneteenth became a legally recognized holiday in Texas in 1980, gaining broader public acknowledgment in the 1990s and nationally in 2021.