During the early 1870s, African American political participation in Texas reached its peak. Black voter turnout was high, and Black men held elected positions at every level of government. These gains were the result of sweeping federal interventions in the late 1860s after the defeat of the Confederacy in the Civil War. Texas was placed under military rule as part of the Fifth Military District, and Congress required the state to extend suffrage to Black men as a condition for readmission to the Union. The Constitution of 1869, drafted under federal supervision, explicitly guaranteed voting rights and made Black political officeholding legally possible for the first time.

Yet from the final years of Reconstruction through the turn of the twentieth century, African American officeholders in Texas faced a relentless erosion of their political standing. By 1900, their numbers had dwindled to near zero. This decline was the result of deliberate legal, structural, and extralegal strategies—including violence and intimidation by groups like the Ku Klux Klan—designed to dismantle Black political power in Texas.

Reconstruction’s Promise

The political rise of African Americans in Texas began in earnest in the late 1860s, a period known as “Reconstruction,” particularly after Congress passed the Reconstruction Acts in 1867. This legislation placed Texas under temporary military rule and required former Confederate states to ratify the Fourteenth Amendment, draft new state constitutions guaranteeing Black male suffrage, and disqualify former Confederates from holding office unless amnestied. Coupled with the presence of federal troops, these measures laid the groundwork for Black participation in politics.

Additionally, Reconstruction in Texas was supported by federal agents of the Freedmen’s Bureau, who operated across the state to assist formerly enslaved people with housing, education, labor contracts, and legal access. Staffed largely by Northern-born agents, military officers, and teachers—labeled “carpetbaggers” by their critics—the Freedmen’s Bureau became a symbol of federal intervention in Southern life.

Officially known as the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, the bureau played a central role in organizing schools, supervising elections, and helping enforce the civil rights of Black Texans during the immediate postwar years. Freedmen’s Bureau agents and federal troops conducted voter registration drives in 1867–68, and Black men voted for the first time in statewide elections in 1869. Military officials also intervened in local conflicts, reinforcing Republican rule during this period.

These interventions resulted in a period of remarkable, though short-lived, Black representation in 19th century Texas. Between 1870 and 1897, at least 52 African American men served in the Texas Legislature, including notable figures like George T. Ruby, a powerful orator and organizer in the early 1870s who became a key ally of Governor Edmund J. Davis; and Elias Mayes, a farmer and Methodist Episcopal minister from Brazos County who served two sessions in 1879 and 1889.

These lawmakers advocated for public education reforms, Black labor rights, fair jury selection, fair prison conditions, and voting access, as well as more equitable treatment of Blacks in day-to-day affairs.

Other African American leaders held local office, especially in East Texas and the Brazos River Valley. Many Black officeholders were Republicans, the party of Lincoln and Emancipation, and found support from Union Leagues and local political clubs.

In counties with large Black populations, especially across the East Texas ‘Black Belt,’ Reconstruction came close to social revolution. As J. Morgan Kousser has written of the South more broadly, this was the moment “the black masses with a few white allies took over many of the local offices”—a radical shift in political power that was most visible in former slaveholding strongholds.1

This dynamic played out in places like Washington, Harrison, Fort Bend, and Brazos counties, where African Americans organized politically through churches, schools, and local Republican clubs. In these pockets of rural East Texas, they elected Black sheriffs, commissioners, and justices of the peace, often with the backing of white Republican allies.

However, Texas’s early experiment in biracial democracy was vulnerable. The majority of the White population, led by the former planter class, did not change their racial views during Reconstruction. Professor Kousser, an expert on Segregation and Southern politics, explains,

“The vestiges of the antebellum ideology and social structure—the unqualified belief in the innate inferiority or even inhumanness of the Negro, the contradictory impulses to violence and paternalism, the acceptance of the hegemony of a tiny white elite—retained their greatest strength after the War among whites in these counties.”2

The Turn Begins: 1873–1880

Historians debate when exactly to mark the end of the Reconstruction period, since it was a process rather than a single moment. One key date is March 30, 1870, when President Ulysses S. Grant signed the act readmitting Texas to the Union. The Fifth Military District, which had exercised federal authority over Texas since 1867, was subsequently dismantled, and most federal troops were withdrawn. Yet Republican control of the state government persisted for several more years under Governor Edmund J. Davis.

Another milestone is September 1, 1872, when the Freedmen’s Bureau formally ceased operations in Texas, ending federal oversight that had supported Black civil rights and education.

A third pivotal moment came on December 2, 1873, when Democrat Richard Coke decisively defeated Davis, a former Union general, in the gubernatorial election. Despite a Texas Supreme Court ruling invalidating the election and the armed occupation of the Texas Capitol by Coke’s loyalists, Grant declined to send federal troops to enforce Davis’s claim. Davis ultimately left office peacefully, marking the collapse of Republican rule and the beginning of nearly a century of Democratic dominance in the state.

Lastly, on February 15, 1876, Texas voters adopted a new state constitution, following a convention dominated by ex-Confederates. This constitution decentralized government authority—a clear reaction to Reconstruction’s centralized control under Republican rule—and has remained the state’s guiding document ever since.

Collectively, these transitional years came to be known among Confederate sympathizers as the period of “Redemption”—signaling the rollback of federal oversight and the resurgence of Democratic power.

However, the end of Reconstruction policies didn’t instantaneously end Black political representation. Throughout the 1870s and into the 1880s, African Americans continued to vote and win office, even as their position was increasingly precarious. The first statewide segregation law wasn’t enacted until 1891, and the Whites-only Democratic primary system wasn’t formalized until 1905.

In the 1880 election, voter turnout among Blacks in Texas was higher than Whites.3 Black political participation remained robust in some regions, even as it came under growing assault from both formal and informal mechanisms.

Violence in the 1880s and 1890s

Throughout the 1880s and 1890s, Black officeholders and their White Republican allies faced mounting barriers to participation. In many parts of Texas, simply running for office—or even supporting the Republican Party—could invite economic retaliation, social ostracism, or deadly violence. White supremacist organizations, including the Ku Klux Klan and local “White Man’s Clubs,” used threats, beatings, and lynchings to terrorize Black political leaders, voters, and White allies. Election days were marred by fraud, intimidation, and strategic vote miscounts.

Tensions were especially high in counties with sizable Black populations where multiracial Republican coalitions had survived beyond the end of Reconstruction. One example was Fort Bend County, where a violent power struggle, later called the Jaybird-Woodpecker War, erupted between the all-White Jaybird Democratic Association and a biracial coalition that had governed that county for nearly 20 years. Sheriff Jim Garvey, who was associated with the ruling Woodpecker faction, was gunned down in broad daylight. The Jaybirds took over and ousted the last remaining Black politicians in the county.

Another well-documented cases came from Washington County, where three white Republicans—Stephen A. Hackworth, James L. Moore, and Carl Schutze—submitted a petition to the U.S. Senate in 1887 detailing a campaign of intimidation and state-sanctioned violence. All were respected local figures: Hackworth was a real estate dealer, Moore a former sheriff, and Schutze the editor of the German-language Republican newspaper Staats Zeitung. Their support for Republican candidates, including African Americans, made them targets.

In their petition, they stated that they had been “compelled to abandon their property at a great sacrifice,” and that “armed and lawless bands of ruffians have taken possession of and destroyed certain ballot-boxes in said county… and have murdered three citizens of said county, and overthrown republican government therein.”4

The petitioners described being driven from their homes in Washington County solely for their affiliation with the Republican Party. Armed threats, political violence, and the collapse of legal protection made it impossible for them to remain.

They also described the coordinated lynching of three Black Republicans—Alfred Jones, Shadrach Felder, and Stewart Jones—who were, they alleged, “delivered by said civil authorities into the hands of large numbers of armed and disguised men—known as Ku-Klux—who wantonly and cruelly hung them to death.” No protection was offered, and no prosecution followed, despite repeated appeals for justice.

The petitioners concluded with a chilling observation: “There exists no republican government in said Washington County… large numbers of citizens… are now in great peril,” and others were “unable and unwilling to leave said county, [yet] are now in great peril, and in their behalf your petitioners… appeal to you for their relief and protection.” Their testimony—delivered formally to Congress—illustrates that the collapse of Black political power was no accident of history, but a coordinated campaign to destroy multiracial democracy by force.

These events were not isolated. In many counties, Klan groups—which went by local names such as Pale Face, Knights of the White Camellia, or the White Brotherhood—and complicit officials used terror and procedural manipulation to eliminate Republican opposition.

Gerrymandering, Poll Tax, and the White Primary

Even where violence was absent, legal mechanisms did the work of exclusion. Gerrymandering diluted Black voting strength. Registration requirements and complex ballot designs made voting more difficult. Though White primaries and poll taxes would not be fully codified statewide until the early 20th century, these tactics of exclusion were already being tested and refined locally in Klan strongholds like Washington County.

By 1900, African Americans in Texas retained few formal avenues for political influence. The civic energy of Reconstruction had been systematically dismantled.

Many Blacks in Texas defected from the Republican Party in the 1890s to the new Populist Party, which made conscious efforts at biracial organizing. Populists courted Black voters, particularly in rural areas, and occasionally supported African American candidates for local office. Yet these alliances were unstable and often undermined by racial suspicion or sabotage by Democrats. The party soon collapsed, and thereafter no major party in Texas offered a viable path for Black political representation, until nearly a century later.

Changes within the state and national Republican Party further weakened its power in Texas and its ability and willingness to defend the Reconstruction order. It fractured into competing “Black and Tan” and “Lily White” factions, and its commitment to racial equality weakened. The “Lily Whites” sought to attract more White voters by minimizing Black participation and leadership. Though the national Republican Party still nominally supported Black voting rights, its actual involvement in Southern states like Texas was minimal compared to the robust engagement of the late 1860s and early 1870s.

The final devastating blows came in 1902 and 1905 with the adoption of the poll tax and party primary rules excluding Blacks. The poll tax, authorized by constitutional amendment and implemented beginning in 1902, required voters to pay a fee—often months in advance of the election—in order to cast a ballot. Though race-neutral on its face, the tax disproportionately disenfranchised African Americans, Mexican Americans, and poor white tenant farmers. Its effect was immediate and enduring: voter participation plummeted across the state, especially in rural counties with large Black populations.

In 1905, the Texas Legislature authorized political parties to set their own rules for primary elections. The Democratic Party—the dominant political force in Texas—soon adopted whites-only rules, effectively barring Black Texans from the one election that truly mattered in most races. In a one-party system, exclusion from the Democratic primary meant exclusion from meaningful political participation. This system of primary disenfranchisement remained in place for decades and was not overturned until Smith v. Allwright (1944), when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled it unconstitutional.

The End of an Era

By the late 1890s, African American elected officials had nearly vanished from Texas government. The last Black legislator of the 19th century, Robert Lloyd Smith, represented Colorado County in the House from 1895 to 1899. A school principal and former land agent, Smith was highly respected and advocated for educational reforms and vocational training.

After Smith left office, no African American would serve in the Texas Legislature again throughout the Jim Crow era until 1966—nearly seven decades later—when Barbara Jordan and Joe Lockridge were elected to the Texas House.

Though their time in office was short, Black officeholders of the Reconstruction and post-Reconstruction era left a deep imprint. They secured funding for schools and other public services for Blacks—though these were usually segregated—and inspired later generations of Black civic leaders. Their legacy endured quietly through churches and community institutions until the Civil Rights Movement of the 20th century reopened the doors of political participation. In recent decades, historians have worked to recover the stories of these first Black statesmen of Texas, honoring a generation that dared to govern in the face of hostility.

Sources Cited

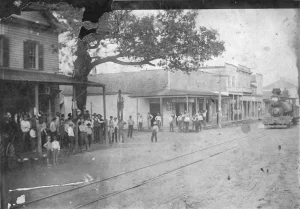

Illustration, top, courtesy of Texas Highways Magazine, originally published in 2021.

- J. Morgan Kousser, The Shaping of Southern Politics: Suffrage restriction and the establishment of the one party South, 1880 to 1910 (Yale University Press, 1974), pg 16. ↩︎

- Ibid., pg. 16 ↩︎

- Ibid., pg 15 ↩︎

- U.S. Senate Committee on Privileges and Elections. Testimony on the Alleged Election Outrages in Texas. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1889, pg. 1–4. ↩︎