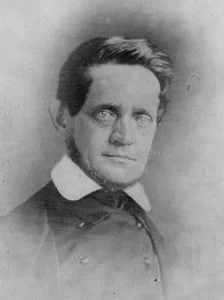

John Hemphill (1803–1862), often called the “John Marshall of Texas,” played a decisive role in establishing the legal foundation of Texas during its transformation from an independent republic to a U.S. state. Known for his scholarly depth, his command of Spanish and Mexican law, and his liberal approach to property and marital rights, Hemphill served as chief justice of both the Republic and State Supreme Courts before concluding his career as a U.S. senator and Confederate delegate.

Early Life and Legal Education

Born in Chester District, South Carolina, on December 18, 1803, Hemphill was the son of a Presbyterian minister of Ulster Scots descent. He attended Jefferson College in Pennsylvania, graduating second in his class in 1825. After teaching school, he read law under David J. McCord and was admitted to practice in South Carolina’s courts of common pleas in 1829 and in chancery courts in 1831. An ardent supporter of states’ rights, Hemphill edited a nullification newspaper in Sumter during the crisis of 1832–33 and briefly served as a second lieutenant in the Seminole War in 1836, where he contracted malaria.

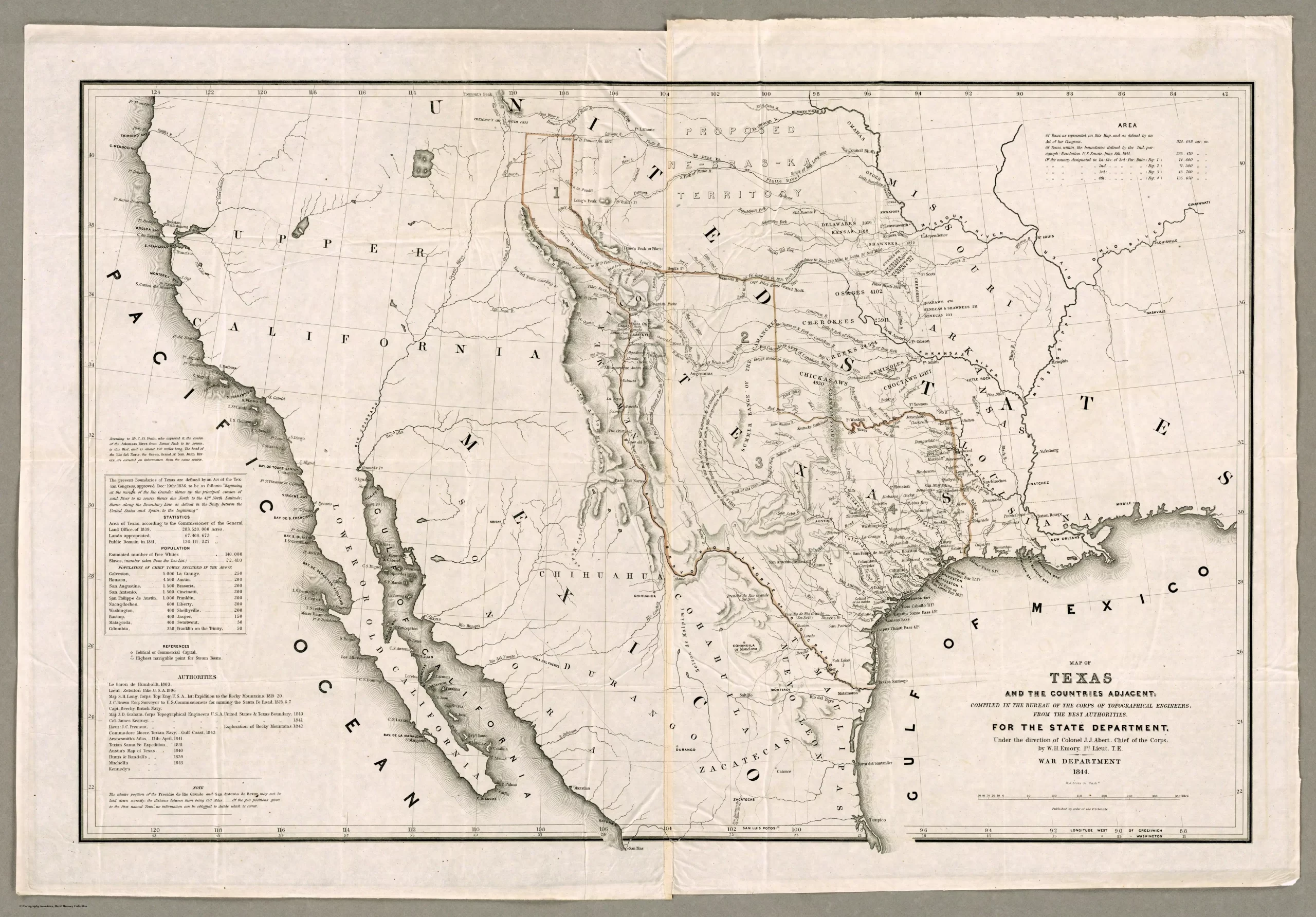

In 1838, Hemphill relocated to the Republic of Texas, settling at Washington-on-the-Brazos. Recognizing the centrality of Spanish and Mexican legal traditions in Texas, he deliberately taught himself Spanish and immersed himself in civil law texts—a scholarly investment that would define his judicial career.

Judicial Career in the Republic of Texas

Hemphill’s entry into the Republic of Texas judiciary came in 1840, when Congress elected him judge of the Fourth Judicial District, a role that made him an ex officio associate justice of the Supreme Court. Later that year, he was elevated to Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the Republic of Texas, succeeding Thomas Jefferson Rusk. He held this post until statehood in 1846.

His early years on the bench were marked by legal uncertainty and personal hardship. Court sessions were infrequent, judicial salaries were often unpaid, and Texas faced external threats from Indian raids and Mexican incursions. In fact, Hemphill joined the Somervell Expedition in 1842 as adjutant general during a lull in court proceedings. He also famously took part in the Council House Fight in San Antonio in 1840, where he was attacked by a Comanche chief and killed his assailant in self-defense with a bowie knife.

Despite these conditions, Hemphill’s opinions, collected in Dallam’s Decisions, helped create a working jurisprudence for a new republic. His rulings emphasized clarity, fairness, and fidelity to the civil law. He was especially forceful in reminding lawyers that Spanish and Mexican legal principles—not English common law—governed many issues before the court.

In cases like Scott v. Maynard (1843), Hemphill urged attorneys to consult Spanish legal authorities directly. He wrote, “The court appreciates the difficulty arising from the scarcity of books or authorities on questions arising under the former laws of the country. But it is clearly the duty of the attorneys to exhaust all which may be accessible to them before they turn for assistance to the common law or any other system of law.”

Role During Early Statehood

With Texas’ admission to the Union in 1845, Hemphill played a leading role at the state constitutional convention. As chair of the Judiciary Committee, he helped shape the judicial article of the 1845 Constitution, favoring a three-judge Supreme Court with appointments made by the governor. This design corrected a flaw in the republic’s constitution, which had given the district court judges the dual role of serving as associate justices of the Supreme Court, making it difficult to attain a quorum and undermining the effectiveness of the Supreme Court in the Republic era.

He successfully defended the Texas practice of merging law and equity in a single court, and he strongly opposed jury trials in equity proceedings—arguing such a change would undermine the specialized nature of chancery law.

Hemphill was reappointed Chief Justice by Governor James Pinckney Henderson in 1846 and later elected to the position in 1851 and 1856 under the new constitutional rules. Over the next decade, he wrote dozens of influential opinions that clarified land titles, defined marital property rights, upheld homestead protections, and incorporated Spanish inheritance doctrines into Texas jurisprudence.

His decisions reflect both deep learning and practical sensitivity. He favored a broad construction of women’s property rights and often spoke critically of common law doctrines that subjugated married women’s legal status. In Wood v. Wheeler (1851), he wrote:

“Husband and wife are not one under our laws. The existence of a wife is not merged in that of the husband. Most certainly is this true so far as the rights of property are concerned. They are distinct persons as to their estates. When property is in question, he is not a baron, nor is she covert, if by the former is meant a lord or master, and by the latter, a dependent creature, under protection or influence. They are coequals in life; and at death, the survivor, whether husband or wife, remains the head of the family.”

He similarly championed homestead exemptions and community property rules rooted in Mexican law—traditions that have remained core features of Texas law ever since.

Senate and Confederate Service

In 1857, as divisions over slavery deepened, Texas Democrats declined to renominate Sam Houston to the U.S. Senate, citing his opposition to secession. Hemphill was selected in his place and began serving in 1859. In the Senate, he supported Southern rights and the doctrine of state sovereignty.

On January 6, 1861, he joined a group of Southern senators urging immediate secession. By July of that year, he was formally expelled from the U.S. Senate along with 13 others. Hemphill then served as a delegate to the Provisional Confederate Congress, participating on key committees including Finance and Judiciary. He worked to adapt U.S. federal laws for Confederate purposes and advocated for Southern independence in formal speeches.

Though he ran for a seat in the First Confederate Congress later that year, Hemphill was narrowly defeated by Williamson S. Oldham. He died of pneumonia on January 4, 1862, in Richmond, Virginia, during the final weeks of the Provisional Congress.

Personal Life and Legacy

A reserved and scholarly man, Hemphill never married. However, he maintained a long-term relationship with his enslaved housekeeper, Sabina, with whom he had two daughters. Remarkably, he arranged for their education at Wilberforce University in Ohio, one of the first Black institutions of higher learning in the United States, which had ties to abolitionists.

Despite the complexity of his personal life and his alignment with the Confederacy, Hemphill’s professional legacy is marked by lasting contributions to Texas law. He was widely respected by contemporaries and later jurists. Chief Justice O.M. Roberts noted that Hemphill gave special attention to the literary excellence of his opinions and maintained “a reserved dignity” in court.

The city of Hemphill, Texas, and Hemphill County are named in his honor. His influence endures most clearly in the elements of Texas jurisprudence that he helped shape: the integration of civil and common law traditions, the protection of homesteads, and the equitable treatment of spouses under the law.

📚 Curated Texas History Books

Dive deeper into this topic by purchasing any of these handpicked titles:

- Lone Star Law: A Legal History of Texas

- Latin American Law: A History of Private Law and Institutions in Spanish America

- Laws and Decrees of the State of Coahuila and Texas, in Spanish and English

- History of the American Frontier – 1763-1893

As an Amazon Associate, Texapedia earns a commission from qualifying purchases. Earnings are used to support the ongoing work of maintaining and growing this encyclopedia.