As governor of Texas during the 1950s, a pivotal decade for the Civil Rights movement, Allan Shivers was a leading supporter of racial segregation in schools and public places. At the time, racial segregation meant that Black and White Texans were required by law and custom to attend separate schools, use separate restrooms, sit in different sections of buses and theaters, and live in strictly divided neighborhoods.

This system, commonly referred to as ‘Jim Crow,’ was enforced across the American South, including in Texas. Rooted in the legacy of slavery, Jim Crow laws and customs kept Black Americans in positions of political, economic, and social inferiority.

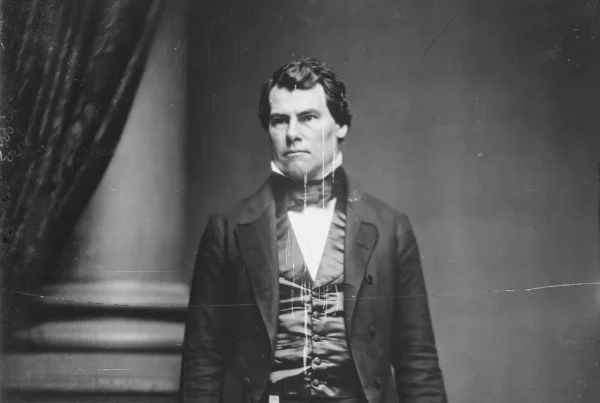

Shivers became governor in July 1949 following the death of Beauford Jester, after serving as lieutenant governor (1947–1949) and, before that, as a Texas state senator (1935–1947). He is the only lieutenant governor in Texas history to ascend to the governorship due to the death of a sitting governor. At just 41 years old, he quickly consolidated power. In the 1950 election, he defeated Republican Ralph W. Currie with 89.9% of the vote.

Two years later, in a rare and controversial arrangement, Shivers was nominated by both the Democratic and Republican parties in Texas and went on to win over 98% of the vote in the general election. His popularity gave him an unusually free hand to direct the course of state government, even as national political loyalties were beginning to fracture.

While best known for his opposition to federal civil rights policy, Shivers also presided over significant growth in the Texas state government. His administration expanded funding for highways, public universities, and mental health facilities. Much of this expansion was made possible by the 1953 resolution of the Tidelands controversy, which secured state control over offshore oil revenues. Under Shivers, the office of the governor gained new influence over state agencies through appointments and policy coordination.

Opposition to Desegregation

Shivers’s most controversial legacy stems from his aggressive and sustained opposition to school desegregation. In the wake of the Supreme Court’s landmark decision in Brown v. Board of Education (1954), which declared racially segregated schools unconstitutional, Shivers declared that Texas would not comply. He denounced the ruling as judicial overreach and warned that integration would provoke social unrest.

Invoking the doctrine of “interposition,” Shivers asserted that individual states had the authority to reject federal mandates deemed unconstitutional—a legal theory rooted in earlier states’ rights arguments used to resist Reconstruction and civil rights reforms.

In 1956, Shivers took the extraordinary step of ordering the Texas Rangers to Mansfield, where a federal court had ordered the integration of the local high school. Rather than enforce the court’s decision, the Rangers blocked Black students from entering the school, and white mobs gathered in open defiance of federal law. No students were harmed, but the outcome was clear: Mansfield High remained segregated.

This episode, one of the first high-profile acts of school desegregation resistance in the South, occurred months before the more widely known crisis in Little Rock, Arkansas, and signaled Texas’s willingness to stand with other Southern states in opposing federal civil rights enforcement.

Shivers also supported a series of state legislative efforts aimed at undermining integration. These included proposals to amend the Texas Constitution, authorize public tuition grants to White students attending private segregated schools, and empower local communities to sidestep desegregation orders. Though many of these measures were ultimately overturned or blocked by federal courts, they created a chilling effect that delayed school integration and enabled continued racial separation well into the 1970s.

Though Brown v. Board struck down formal segregation in education, many schools and public places across Texas remained effectively segregated long after Shivers left office. Even the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and subsequent court rulings failed to fully dismantle the racial inequalities embedded in Texas society. In this context, Shivers’s opposition to desegregation was not an isolated stance—it reflected widespread social beliefs within Texas.

Break with the National Democratic Party

By the early 1950s, Shivers had become a central figure in the political realignment taking shape across the South. In the 1952 presidential election, he endorsed Republican Dwight D. Eisenhower over Democratic nominee Adlai Stevenson, citing Eisenhower’s support for Texas’s claim to offshore oil lands in the Tidelands controversy.

More significantly, Shivers viewed the national Democratic Party as increasingly aligned with civil rights reform and federal intervention—positions that conflicted with the racial and political order favored by many Southern leaders.

Shivers led a faction of conservative Texas Democrats who supported Eisenhower while remaining on the state ballot as Democrats. This group came to be known as “Shivercrats,” echoing the earlier “Dixiecrat” revolt of 1948, in which Southern Democrats walked out of the national convention to protest President Truman’s civil rights platform.

Unlike the Dixiecrats, who formed a short-lived third party, the Shivercrats remained within the state party structure while working to undermine national Democratic candidates. The episode marked an early stage in the South’s gradual political realignment, as conservative White voters eventually abandoned the Democratic Party in response to its shifting stance on civil rights.

The Shivercrat revolt did not result in an immediate partisan shift, but it laid the foundation for future Republican gains in Texas by legitimizing conservative dissent within the Democratic Party. Over the next two decades, many Texas Democrats would follow a similar path.

The Tidelands Controversy and State Sovereignty

One of the defining political fights of the Shivers administration was the Tidelands controversy, a dispute over ownership of the submerged lands off the Texas coast—believed to contain vast oil reserves. The federal government, under President Harry Truman, claimed jurisdiction over these lands, while Shivers and other Texas officials insisted they belonged to the state under its terms of annexation.

Shivers made the Tidelands issue a litmus test of state sovereignty. He tied his support for Eisenhower in 1952 directly to the candidate’s position on the issue. After Eisenhower’s victory, Congress passed the Submerged Lands Act of 1953, which restored Texas’s control over its coastal waters and mineral rights. The victory brought billions of dollars in oil royalties to the Permanent School Fund, dramatically boosting the state’s fiscal capacity.

The Tidelands victory reinforced Shivers’s image as a defender of Texas interests and energized his broader campaign for state control over civil affairs.

Growth of State Government and Institutional Capacity

Although best known for his opposition to desegregation and his break with national Democrats, Shivers remained firmly within the dominant Southern Democratic tradition of the 1950s. He did not oppose government itself but opposed federal government expansion at the expense of state control. During his time in office, Shivers oversaw the growth of Texas’s own institutions, funded largely by new oil revenues.

His administration invested heavily in public infrastructure, highway expansion, state hospitals, and higher education. Funding for the University of Texas and Texas A&M increased significantly. The state also expanded mental health facilities and civil defense programs during the early Cold War years. Shivers used his influence over appointments to boards and commissions to assert gubernatorial control over a growing bureaucracy, despite the formal limits of executive power under the Texas Constitution.

This growth reflected the lingering influence of the New Deal framework, in which Southern states often embraced public investment and professional administration, while parting ways with national Democrat leaders over federal control, race, and labor unions.

Yarborough’s 1954 Primary Challenge

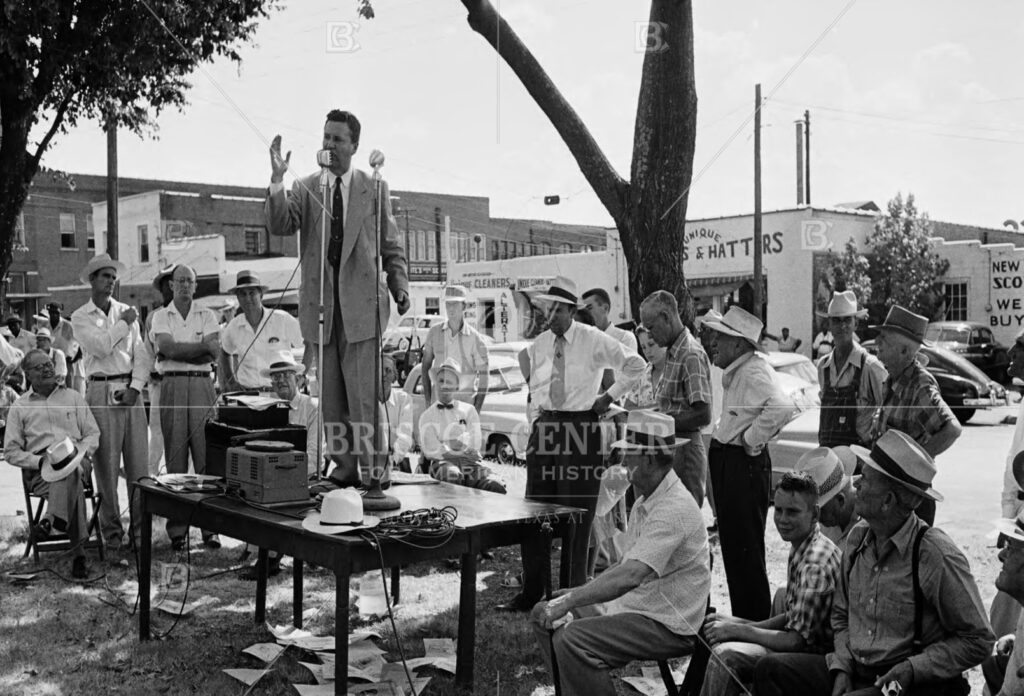

In the 1954 Democratic primary, Allan Shivers faced a serious challenge from Ralph Yarborough, a rising liberal voice in Texas politics. Yarborough, a former district judge and outspoken advocate for public education and civil liberties, nearly defeated Shivers in the first round of voting, earning 47.8% to Shivers’s 49.5%, forcing a runoff.

The campaign became sharply polarized, with Shivers and his allies portraying Yarborough as sympathetic to federal civil rights efforts and “soft on communism,” a potent charge during the height of McCarthy-era politics. This rhetoric echoed national fears about subversion and reinforced Shivers’s appeal to conservative voters who viewed civil rights, labor activism, and federal oversight through the lens of Cold War suspicion.

Yarborough, by contrast, emphasized ethical government, transparency, and expanded social services, drawing strong support from urban liberals, labor groups, teachers’ organizations, and minority communities. He openly criticized the Shivers administration over the Veterans Land Board scandal, which defrauded hundreds of World War II veterans—many of them Black and Tejano. The program, overseen by Land Office Commissioner Bascom Giles under Shivers’s watch, involved block land sales that bankrupted participants and inflicted severe financial harm. Although Giles was the only official convicted, Shivers and Attorney General John Ben Shepperd were publicly implicated as ex officio members of the board, raising questions about the administration’s ethical oversight.

Despite these charges, Shivers narrowly defeated Yarborough in the 1954 runoff, securing 53% of the vote to Yarborough’s 47%. The near upset energized the liberal wing of the Texas Democratic Party, boosted Yarborough to an eventual U.S. Senate victory, and foreshadowed deeper fractures that would reshape party identity and political alliances in the decades ahead.

Early Political Career

Allan Shivers rose to the governorship after an earlier career in the Legislature. He entered Texas politics just 27 years old, after graduating law school. In 1934, he was elected to the Texas Senate, becoming the youngest senator in the state’s history. He served in the Senate for over a decade and earned a reputation as a skilled negotiator.

During World War II, Shivers served in the U.S. Army, seeing combat in North Africa and Italy and rising to the rank of major. His military service during World War II reinforced his public image as disciplined and pragmatic leader.

After the war, Shivers returned to politics, winning election as lieutenant governor in 1946. A skilled parliamentarian and political operator, he elevated that office, shaping it into the more powerful legislative position that it would later become. Shivers’s early political profile reflected the centrist New Deal ethos of Texas Democrats at the time—supportive of infrastructure and institutional development, but wary of federal overreach.

Legacy and Historical Assessment

Allan Shivers left office in 1957, at age 50, as one of the most influential and polarizing governors in Texas history. His aggressive defense of racial segregation and states’ rights placed him firmly among the most prominent Southern resistors to civil rights reform. Shivers’ dominance in the 1950, 1952, and 1954 general elections—in which he ran as an avowed segregationist—highlighted the popularity of racial segregation within Texas at the time, as well as the ongoing disenfranchisement of Black and Tejano voters.

At the same time, Shivers’ tenure strengthened the office of the governor, expanded the state’s administrative capacity, and secured major financial victories for Texas through the Tidelands resolution. After retiring from politics, Shivers managed family business holdings in the Rio Grande Valley, and he served on the board of directors for a number of banks.

In the 1970s and 1980s, Shivers served as a regent and chairman of the University of Texas at Austin, and as president of the United States Chamber of Commerce. Shivers donated his family home, the historic Pease Mansion in Austin, to the University of Texas.

After Shivers’ death in 1985, the university sold the home to the state government, using the proceeds to endow professorships in law and fine arts. In the 1990s, Lieutenant Governor Bob Bullock dreamed of making the Pease Mansion into the official new governor’s mansion, but this idea faded after his death, and the state sold the home to a private buyer in 2002.

📚 Curated Texas History Books

Dive deeper into this topic with these handpicked titles:

- Yellow Dogs and Republicans: Allan Shivers and Texas Two-Party Politics

- The Dixiecrat Revolt and the End of the Solid South, 1932-1968

- Historic Photos of Dallas in the 50s, 60s, and 70s

Texapedia earns a commission from qualifying purchases. Earnings are used to support the ongoing work of maintaining and growing this encyclopedia.