Historical Context

In the spring of 1844, the United States and the Republic of Texas signed a formal treaty proposing annexation. Negotiated by the U.S. Secretary of State and Texas commissioners Isaac Van Zandt and J. Pinckney Henderson, the treaty would have ceded all Texas territory to the U.S.

In return, Texans would gain U.S. citizenship and a de facto guarantee of protection from Mexico, which still claimed Texas territory, threatening to invade at any time. Additionally, the U.S. agreed to assume the substantial public debt of the struggling young republic, up to $10 million.

The annexation treaty quickly became a political flashpoint. When submitted to the U.S. Senate in April 1844, it met fierce resistance. Texas was a slaveholding republic, and its annexation was widely seen as an attempt to expand the political power of the pro-slavery faction within the United States.

Annexation also threatened conflict with Mexico, which viewed Texas as a rebellious territory of its own, not a sovereign republic. Even some pro-slavery expansionists, like Missouri Senator Thomas Hart Benton, opposed the treaty. On the Senate floor, Benton denounced the plan as an invitation to war with Mexico, a violation of diplomatic norms, and a sectional gambit that endangered national unity. On June 8, 1844 the Senate voted it down by a vote of 16–35, derailing the diplomatic effort.

Yet this failure proved only temporary. The Texas question then became a central issue in the 1844 presidential election, reshaping the Democratic Party and ultimately leading to the rise of expansionist candidate James K. Polk.

Polk led a renewed push for Texas’s annexation by joint resolution the following year, a maneuver that required only a simple majority in both houses of Congress rather than the two-thirds Senate vote needed for a treaty. The resolution passed the House 120–98 and cleared the Senate by a narrow 27–25 vote—just enough to carry the effort through.

The terms of the joint resolution, however, departed in key ways from those envisioned in the treaty—shaping Texas’s path into the Union through a very different framework. The 1844 treaty would have made Texas a U.S. territory, placing its public lands under federal control. But the 1845 joint resolution, passed instead of a treaty, offered Texas immediate admission as a state, not a territory.

This meant full political representation in Congress from the outset and avoided the transitional status typically applied to new U.S. acquisitions. Additionally, because Texas entered as a state, it was able to retain ownership of its vacant and public lands—a highly unusual privilege not granted to most other states. These lands would later fund Texas schools, universities, and infrastructure through mechanisms like the Permanent School Fund. In short, Texas received a more favorable deal under the joint resolution than it would have under the treaty.

Though never ratified, the treaty text reproduced below remains a foundational document in understanding the legal, political, and economic terms envisioned at the time. It captures a pivotal moment—when annexation was not yet assured, and the future of Texas hung in delicate balance.

For a full history of this period, see:

- The Road to Annexation: Why Texas Joined the United States in 1845

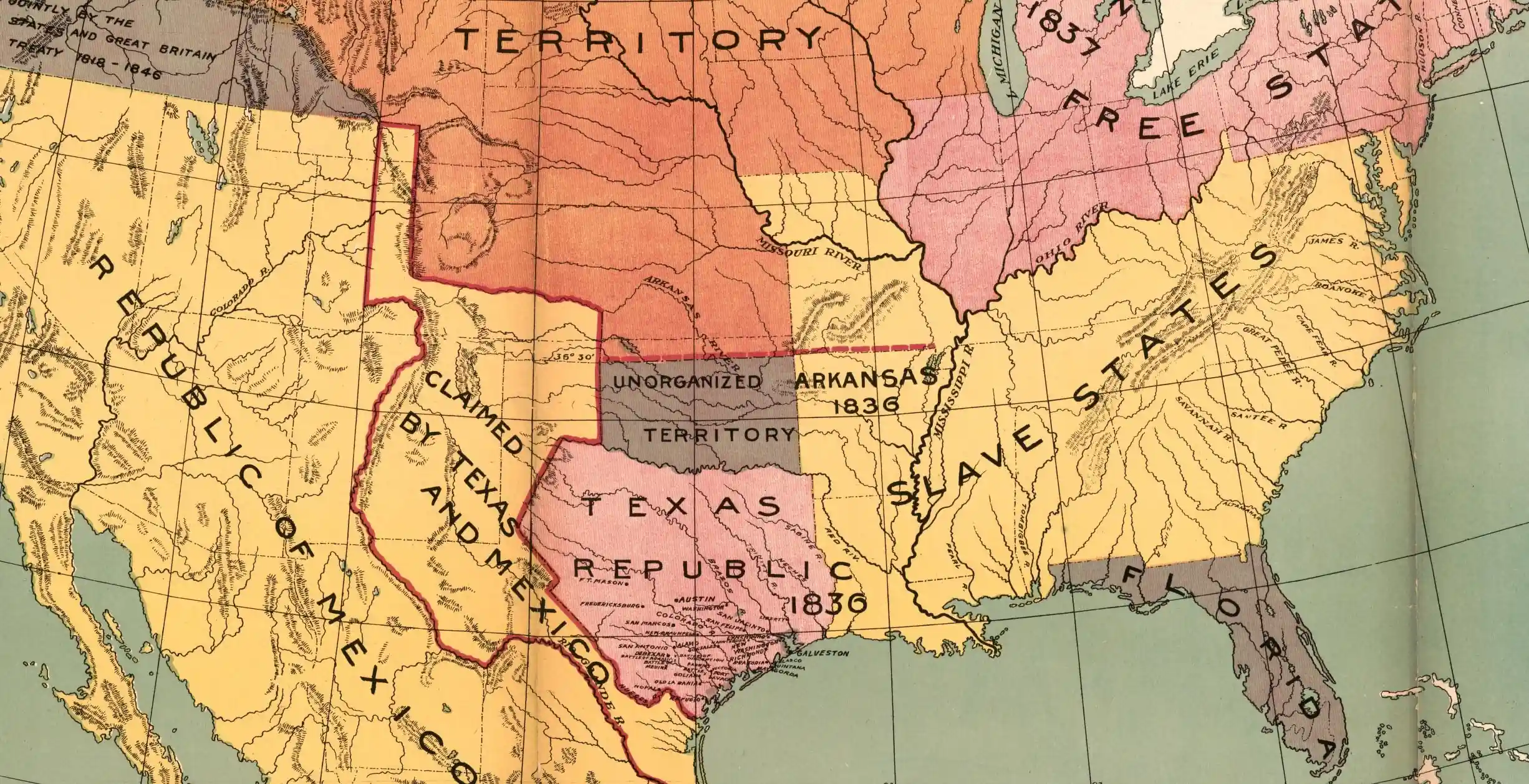

- Map of the Republic of Texas (1844)

A Treaty of Annexation, concluded between the United States of America and the Republic of Texas

April 12, 1844

Note: Article headings and additional paragraph breaks added for readability. The original articles were simply numbered without any descriptive headings.

This article is part of Texapedia’s curated primary source collection, which makes accessible both famous and forgotten historical records. Each source is presented with historical context and manuscript information. This collection is freely available for classroom use, research, and general public interest.