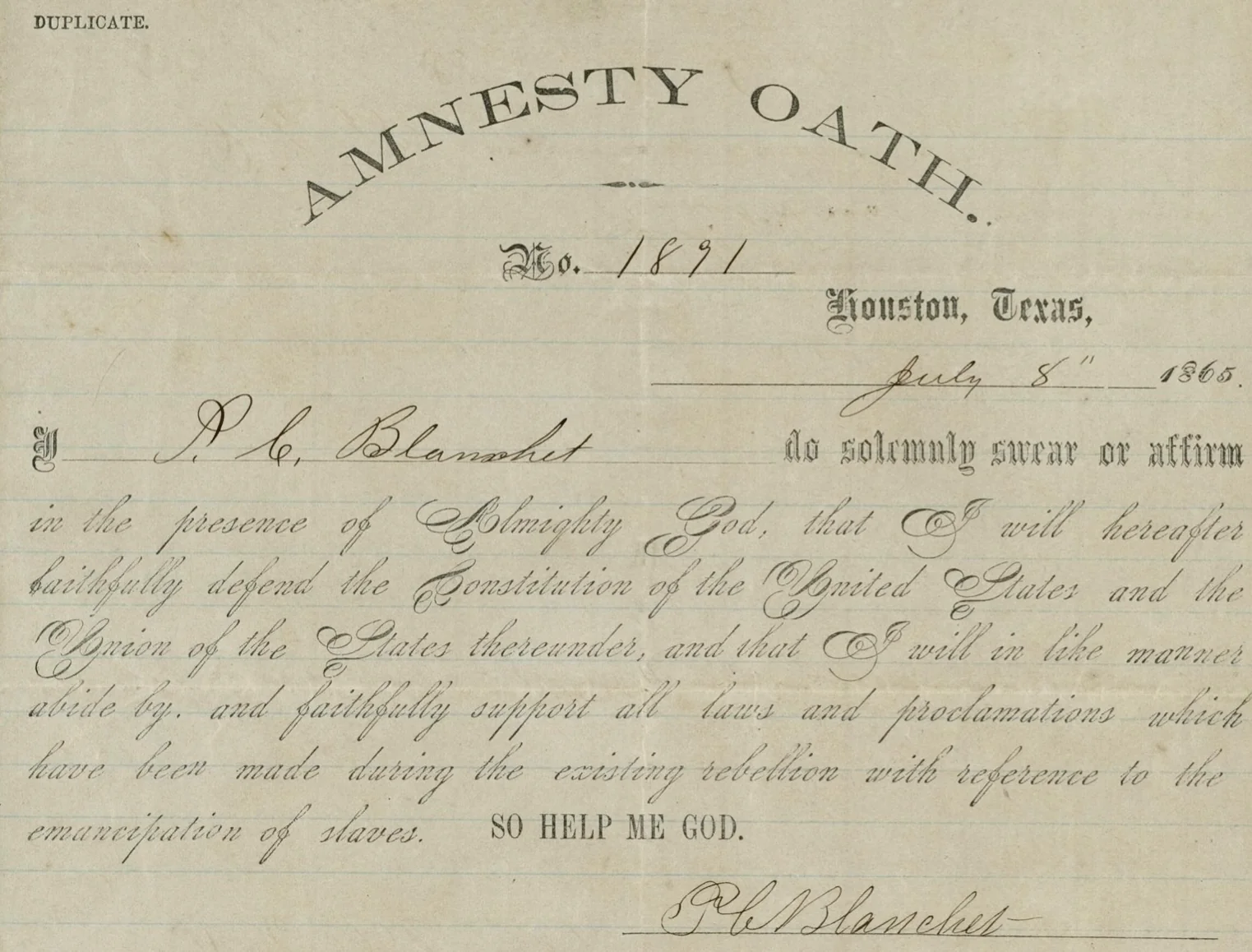

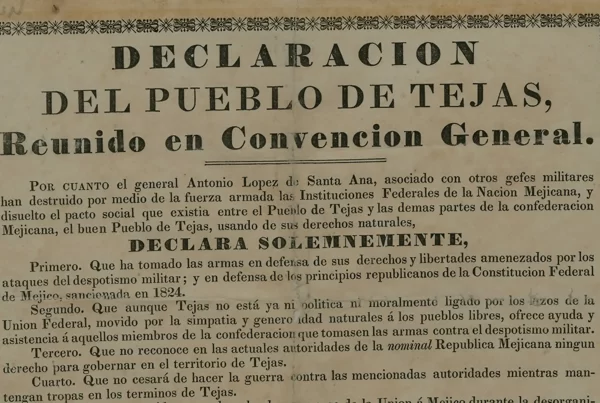

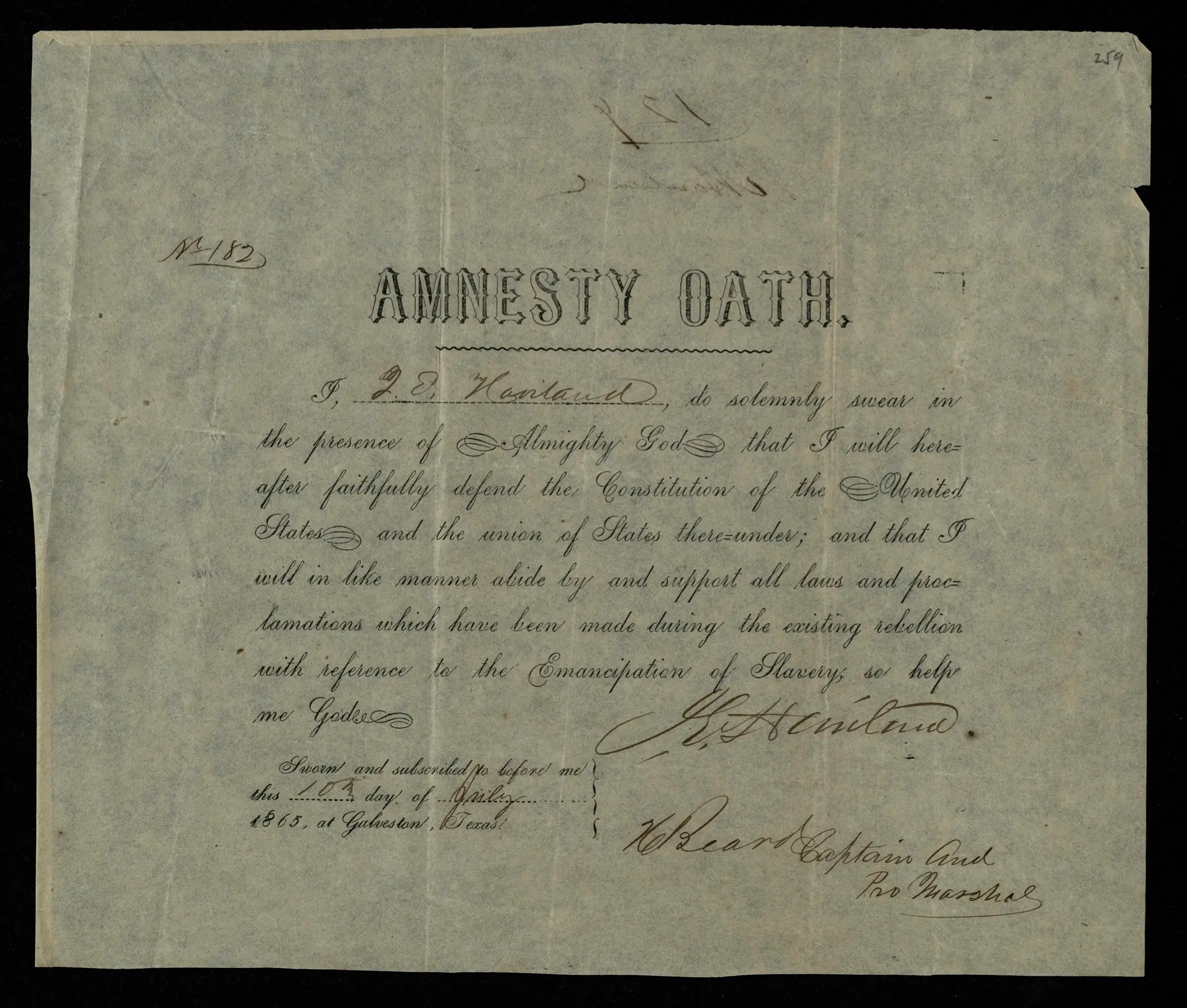

The end of the Civil War ushered in a legal and political reckoning across the defeated South. In Texas, as in other former Confederate states, so-called “amnesty oaths” became a key mechanism for determining who could participate in civic life. These sworn declarations of loyalty to the Union dictated access to voting, public office, and property rights.

The word “amnesty” typically means a broad pardon or official forgiveness for past wrongdoing. In the context of Reconstruction, however, amnesty oaths functioned more as legal tests of loyalty than as unconditional clemency. They applied primarily to former Confederates soldiers and officials. They were required to swear allegiance to the United States in order to vote, hold office, or recover property.

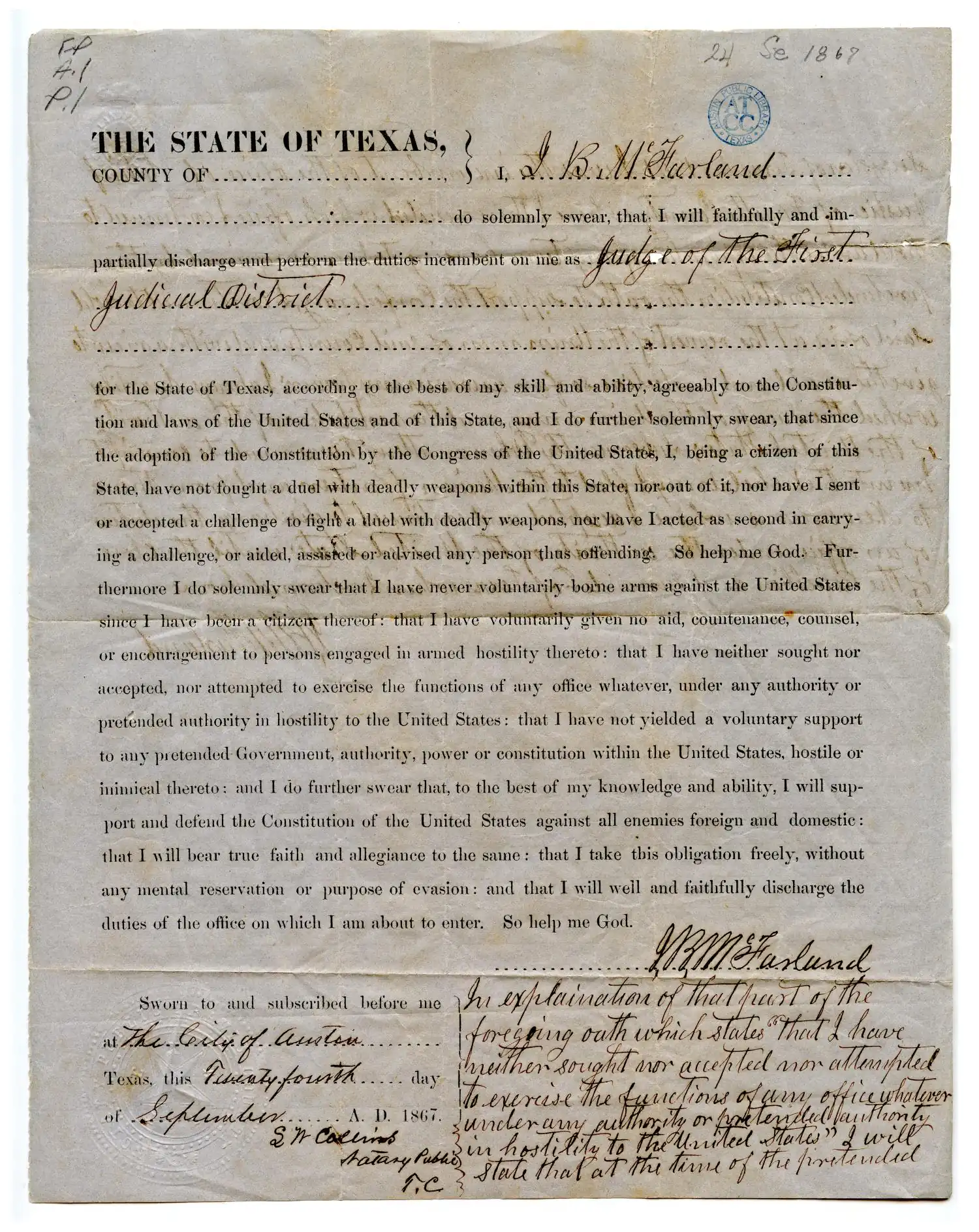

Under Congressional Reconstruction, the requirements grew even more stringent: prospective officeholders had to take an “ironclad oath” affirming they had never voluntarily aided the Confederacy, a condition that excluded a large share of white adult males. Newly enfranchised Black men were not subject to these oaths, as they had not been recognized as Confederate citizens.

In practice, the oaths acted as a gatekeeping mechanism to block secessionists from holding office in postwar Texas. This functioned both as a punishment for their disloyalty during the Civil War, and as a safeguard against their return to power.

Presidential vs. Congressional Reconstruction

The earliest postwar amnesty efforts in Texas were shaped by President Andrew Johnson’s lenient Reconstruction policy. In 1865, Johnson issued a general amnesty proclamation that offered pardons to most former Confederates who would swear a simple oath of allegiance to the United States and agree to abide by the end of slavery. Those who took the oath would be restored to their civil rights and could reclaim most of their property (excluding enslaved people).

However, this blanket approach included exceptions. Certain classes of Confederate leaders and wealthy individuals—such as officers above a certain rank, former members of Congress who had joined the Confederacy, and those with taxable property worth over $20,000—were required to seek individual pardons from the president. In Texas, this included many of the state’s political and military elite, who flooded Washington with letters pleading for clemency. Johnson ultimately granted thousands of individual pardons, allowing many of these figures to return to positions of influence in Texas politics and business.

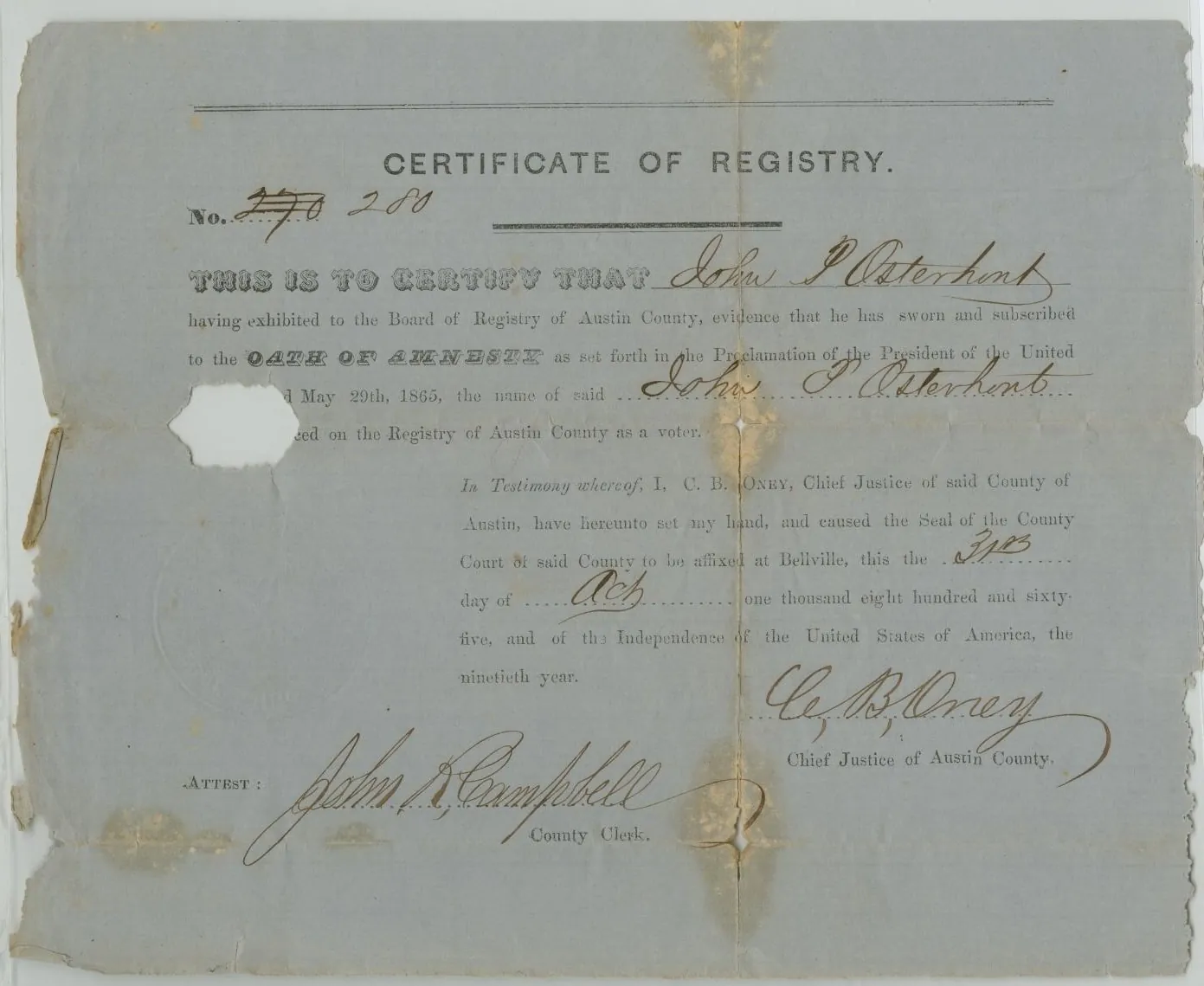

Federal authorities in Texas required prospective voters to take loyalty oaths before being added to official registration rolls. County registrars maintained oath books—bound volumes that recorded the names of those who had sworn allegiance to the United States and affirmed they had not voluntarily supported the Confederacy. Only those who met this standard were permitted to vote or serve as delegates at the pivotal constitutional convention of 1868–69, which produced the new Reconstruction-era constitution.

The Ironclad Oath in Texas

In contrast, Congressional Reconstruction—initiated after Republicans in Congress grew frustrated with Johnson’s leniency—imposed far stricter requirements for amnesty and political participation. The Reconstruction Acts of 1867 placed Texas under military rule and required the state to draft a new constitution guaranteeing Black suffrage. As part of this more radical program, anyone seeking to vote or hold office had to take the “ironclad oath,” swearing that they had never voluntarily supported the Confederacy in any way.

The ironclad oath created significant political disruption in Texas. By disqualifying large swaths of the white male population—especially former Confederate officials, soldiers, and civil servants—it cleared the way for a new political coalition of Unionists, recently enfranchised Black men, and Northern Republicans (often called “carpetbaggers”) to shape the state’s postwar government.

This system of federal oversight, enforced by military officials and registration boards, remained in place until Texas was formally readmitted to the Union in March 1870. After readmission, the ironclad oath requirement was lifted, and many former Confederates regained full political rights.

Loyalty and Local Governance

Beyond state-level politics, amnesty oaths played a crucial role in local governance across Texas. County clerks, judges, sheriffs, and school officials were often required to swear loyalty to the Union before assuming or continuing in office. This disrupted civil administration in many counties, particularly in rural areas where Confederate sympathies had run deep.

In some places, former Unionists and Black Texans gained local offices for the first time, supported by federal authorities and military commanders overseeing the Reconstruction process. However, in other regions, white resistance took the form of passive noncompliance or active intimidation. In parts of East Texas and the Hill Country, where wartime divisions had been especially sharp, political tensions flared as local leaders were removed or replaced based on their past allegiances.

The End of Oath Requirements

The requirement for amnesty and loyalty oaths began to fade with the close of Reconstruction. As Democrats regained control of state government in the 1870s—a process known as Redemption—they repealed many of the restrictions that had been imposed by federal law. The 1876 Texas Constitution, still in effect today (albeit heavily amended), made no provision for the ironclad oath or other political tests based on wartime conduct.

It is debatable whether the oaths were effective at excluding Confederates from power or were counter-productive and hastened the end of Republican rule. The oaths excluded many capable candidates from office—even those who were willing to accept the new status quo and work with the Reconstruction authorities. This created power vacuums in certain areas or forced Reconstruction-era leaders like Governor Edmund Davis to appoint unqualified candidates, merely because they could sign the ironclad oath.

Though the oaths temporarily had the effect of excluding Confederates from power, they were seen as an indiscriminate tool of factional control, provoking backlash and contributing to government breakdown and lawlessness in Texas during Reconstruction..

This article is part of Texapedia’s curated primary source collection, which makes accessible both famous and forgotten historical records. Each source is presented with historical context and manuscript information. This collection is freely available for classroom use, research, and general public interest.