In Spanish and Mexican Texas, the alcalde was essentially a combination of a mayor and a magistrate—a local official wielding both executive authority and judicial power. Much like a modern city mayor, the alcalde oversaw town administration, while also acting as the primary judge for minor civil and criminal cases. This dual role made the alcalde the most important official in a Spanish-era Texas community.

The word alcalde is derived from the Arabic al-qadi, “judge,” dating to the time that Spain was under Muslim rule.

Spanish Texas and the First Alcaldes

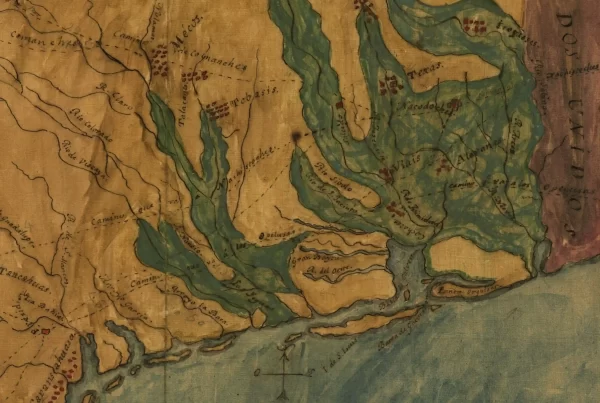

Spanish colonial law introduced the office of alcalde to Texas when permanent civil settlements were established in the 18th century. The first civil government in Texas was formed in 1731, when Canary Islander settlers founded the town of San Fernando de Béxar (today San Antonio). That year, the initial alcaldes were selected in the new town.

Although alcaldes held significant civil authority, they operated within a broader power structure that included military commanders and Catholic missionaries. In frontier presidios and mission towns, the military often maintained ultimate authority over security and land defense, while Franciscan friars oversaw religious and social life. The alcalde served as a local executor of law and order, but his decisions were often shaped by the expectations of the presidio captain or the mission padre, especially in newly settled or indigenous communities.

This threefold system—military, religious, and civil—reflected Spanish colonial policy, which emphasized both territorial control and cultural conversion. In many towns, the alcalde mediated between these spheres, reinforcing imperial norms while responding to local needs.

The alcalde was typically selected annually by the cabildo or ayuntamiento, a local town council composed of prominent settlers. In early Texas, this process was limited to a small circle of eligible men, usually drawn from the local elite. For example, Juan Leal Goraz, one of the Canary Islanders, was chosen by his peers as the first alcalde of San Fernando de Béxar in 1731, effectively becoming Texas’s first mayor-magistrate.1

Other Spanish settlements in Texas developed similar arrangements. Laredo, for instance, held its first selection of alcaldes in 1767 as it shifted from a military outpost to a civilian town. In places like La Bahía (Goliad) and Nacogdoches, as populations grew, formal ayuntamientos were established, and alcaldes were chosen—sometimes appointed, sometimes elected in limited local votes. The 1812 Spanish Constitution introduced broader popular elections for municipal offices, marking a shift toward more participatory governance across the empire, including Texas.

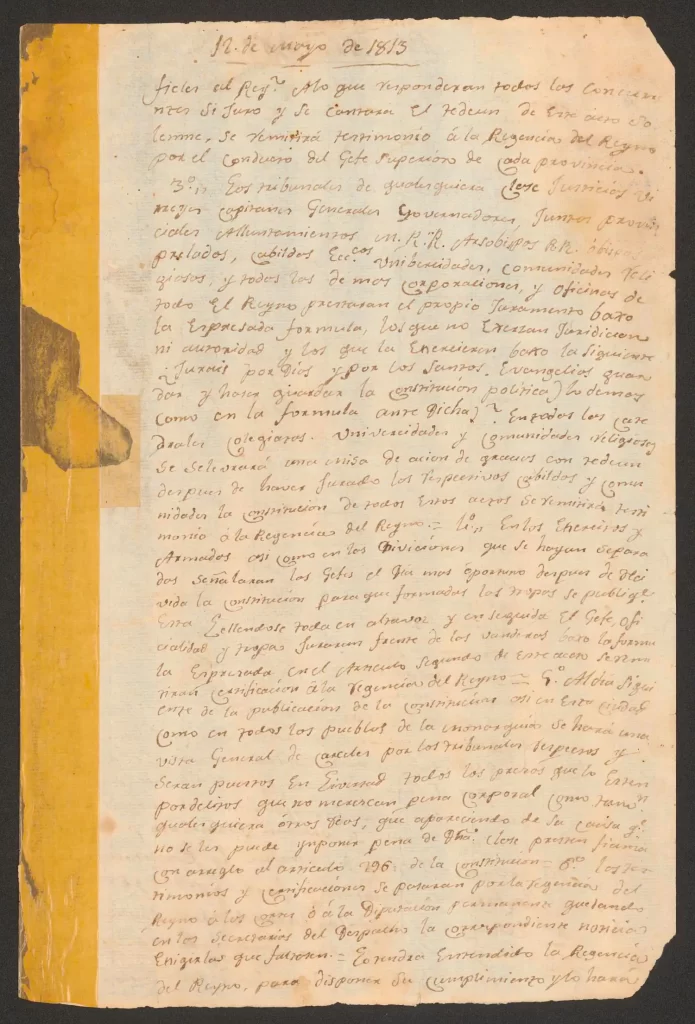

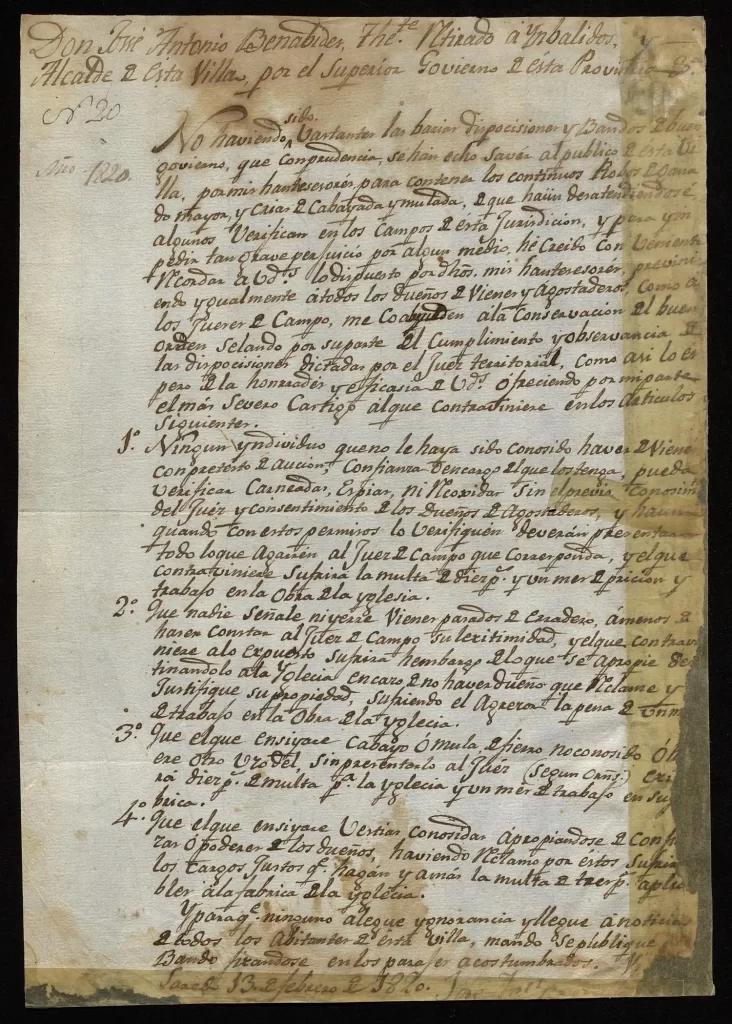

A surviving 1813 document from Laredo illustrates how these reforms reached the Texas frontier. It is a local copy of a royal decree issued by the Regency of Spain, requiring towns to publicly proclaim the Constitution of 1812 and reorganize their municipal governments accordingly. Local officials—including alcaldes—were instructed to swear loyalty to the new constitutional order and enforce its provisions.

The decree reflected an effort to formalize electoral systems and standardize governance in remote settlements. Although this marked a theoretical shift in how authority was structured in practice not much necessarily changed throughout the remote Spanish settlements in Texas. Though the Spanish colonial system was officially centralized and rule-bound, the realities of life on the northern frontier required flexibility.

“All general governors, provincial juntas, municipal councils (cabildos), and other authorities and offices throughout the Kingdom shall conform to the system established by the Constitution… In all towns of the Kingdom, the Constitution must be publicly read and published in a solemn manner, with all the people gathered.”

“The local chief (jefe superior), the judges, and elected officials must swear an oath of fidelity to the Constitution and ensure its observance… the formula to be used is as follows: ‘I swear by God and on the Holy Gospels to uphold the political Constitution of the Spanish Monarchy…”

Implementing order relating to the 1812 Constitution of Cádiz, circulated in Laredo, TX.

Notably, Spanish Texas sometimes had two alcaldes in larger towns: a first and second alcalde, with the primer alcalde ranking higher—a practice used in places like San Antonio when its population warranted more than one magistrate. In the absence of higher officials (such as a corregidor or governor-in-residence), the alcalde was the chief local authority.

Judicial Role of the Alcalde

As local magistrates, alcaldes held primary judicial responsibility in their towns. One of the alcalde’s primary duties was to act as a judge. He would hear and decide cases involving minor crimes, small debts, property disputes, and other local civil or criminal matters within his jurisdiction. In practice, the alcalde handled the vast majority of judicial business in the community, since most everyday disputes fell under “minor” categories by colonial standards. Major crimes, military offenses, or church-related cases were outside the alcalde’s purview and were referred to specialized military or ecclesiastical courts.

Lacking formal legal training in most cases, alcaldes dispensed justice by relying on Spanish legal tradition, common-sense ideas of fairness (equidad), and local customs to resolve disputes. This meant a pragmatic approach to frontier justice, guided by a vague understanding of written law and by what the alcalde deemed fair and necessary for local order.

Although an alcalde’s judgments were not necessarily final, appeals were rare. In Texas in the 1700s and early 1800s, “The population was largely poor, with most eking out a living as farmers. Few colonists in northern New Spain possessed the resources to take legal disputes from the local judges (alcaldes ordinarios) to the provincial governor, and then to the audencia (royal appellate court) in Guadalajara.”2

The alcalde’s courtroom was informal by modern standards—often a room in the casa real (town hall) or even outdoors under a porch. Proceedings did not involve juries, since Spanish law did not use jury trials; the alcalde rendered verdicts based on the law and evidence presented. They could issue fines, order restitution, or prescribe corporal punishments for minor offenses. Enforcement of the alcalde’s judicial decisions was aided by the alguacil (sheriff or constable). There were no jails or prisons, and therefore alcaldes generally preferred restitutive sentences.

Usually, there were no lawyers involved in the proceedings, and the alcalde himself often had no legal training and access to few, if any, written law codes. As a frontier territory, Spanish Texas never had any trained, professional lawyers that assisted with basic civil or criminal litigation. Historian Michael Ariens explains, “No trained lawyer could make a living practicing law in San Fernando de Béxar through the first decades of the nineteenth century [i.e., until after Mexican independence in 1821]… A few self-trained legal writers assisted claimants in San Antonio during this time.”3

Not even the government of the region had a lawyer, until the assignment of an asesor (legal advisor) in the late 1700s, Pedro Galindo Navarro, who possessed a small library of legal books.4 Therefore, though the alcaldes were judges in the sense that they resolved local disputes, they were not judges in a modern sense, in that they did not apply a well-known, written body of law.

The 1820s witnessed the arrival of Anglo-American settlers in East Texas, who brought with them common-law practices, particularly the jury trial. This influenced alcaldes in Spanish-speaking parts of Texas, including San Antonio, to adopt a jury-like system:

“Civil and criminal cases streamed steadily through the alcalde’s court. In both types of cases the alcalde relied on a citizen fact-finding process, formalized by state decree in 1827. In this system, worthy citizens, called hombres buenos or conjueces (assistant judges), were chosen by the accused and the plaintiff to represent their cases. Responsible for examining witnesses, gathering pertinent information, and making recommendations to the court on how to proceed, the citizen conjueces functioned as grand juries, investigators, and counsels. Given the amount of legal detail and sheer paperwork and the lack of trained lawyers, it is little wonder that by 1829 community leaders were expressing the need for an additional alcalde to help handle the judicial burden.”5

Administrative Role and Municipal Governance

Beyond his judicial authority, the alcalde also served as the chief executive of the town. He presided over the ayuntamiento, participated in debates, and held a single vote like other council members—but his leadership role often elevated his practical influence. He coordinated public works, enforced municipal ordinances, and oversaw the allocation of communal lands for farming and grazing.

Under Spanish rule, alcaldes were central to the cabildo or ayuntamiento—terms often used interchangeably to describe the town council. While cabildo referred broadly to the traditional municipal governing body, ayuntamiento came to represent a more formalized and bureaucratic version of the same institution under later Spanish and Mexican law. In both forms, the alcalde served not only as a presiding officer but also as a local agent of royal authority.

The alcalde was the key link between local settlers and higher colonial or state officials. He corresponded regularly with the provincial governor, submitted reports on local conditions, and implemented imperial or state directives. In addition, he supervised public records, ensured law and order, maintained basic public health standards, and adjudicated disputes involving land, livestock, and local welfare.

Supporting the alcalde were other municipal officers, including the síndico procurador (a legal advocate for the public interest), the escribano (secretary), and the alguacil (constable or bailiff). However, the effectiveness of local government often depended less on institutional design than on the competence and initiative of the alcalde himself.

In theory, alcaldes represented royal authority on the frontier, though in practice the weakness of the empire’s central bureaucracies left them to their own devices. This experience of decentralized local rule—shared by alcaldes and other colonial elites across New Spain—helped cultivate the habits of local autonomy that would later inform the push for Mexican independence.

Notable Alcaldes in Texas History

Several individuals stand out in the historical record:

- Juan Leal Goraz (1731): The first elected alcalde of San Fernando de Béxar (now San Antonio), he laid out the town’s initial civic structures and helped establish the model of municipal governance in Texas.

- Juan José Erasmo Seguín (1830s): A respected Tejano leader who served as alcalde of San Antonio. He helped ease the transition from Spanish to Mexican rule and welcomed Stephen F. Austin to Texas. His son Juan became a leader in the Texas Revolution, who helped defend the Alamo and was sent out as a courier to gather reinforcements.

- John Tumlinson Sr. (1820s): One of the first Anglo-American alcaldes in Mexican Texas. Working closely with Stephen F. Austin, he laid the groundwork for law enforcement in Austin’s Colony.

- Samuel Norris (1820s): His disputed election as alcalde of Nacogdoches led to the Fredonian Rebellion—an early sign of tensions between Anglo settlers and Mexican authorities.

- José María Salinas (1820s–1830s): A wealthy rancher, he served multiple terms as alcalde of San Antonio. His leadership helped bridge the Tejano and Anglo communities during a time of great political upheaval.

Transition to Anglo-American Governance

After the independence of Mexico in 1821, the alcalde system continued to operate in Spanish-speaking regions, and was also extended to the American settler colonies in northeast Texas, which the Mexican government initially authorized. As the empresario of the largest colony, Stephen F. Austin was given “wide-ranging powers by the Mexican government,” including certain judicial powers. He created three districts, each governed by an alcalde, with appeals going to Austin himself.6

“The alcalde could hear and judge local disputes, but the loser could appeal to Austin if the amount in question was more than $25. Disputes of more than $200 would go straight to him. Austin kept the Spanish model of trying to settle cases out of court. The presiding judge would first attempt to make a compromise, and then if he could not, either party could request arbitration by somebody else. Actual trials should be a last resort.”7

“Law and the Texas Frontier,” Texas Supreme Court Historical Society, 2018

However, Austin also introduced element of Anglo-American law, such as the right to jury trial, which was not recognized in Mexican law. He allowed the colonists to try cases by jury informally, after which he would confirm their decision as judge.

After the Texas Revolution in 1836, the newly formed Republic of Texas replaced the alcalde system with Anglo-American structures. The municipality became the county, and the offices of alcalde and ayuntamiento were replaced with justices of the peace, county judges, and county commissioners.

Each county had a chief executive (the county judge) and justices of the peace to handle minor legal matters—roles that had previously been united under the alcalde. Over time, the county judge’s powers became more administrative, while judicial authority was more clearly divided among other offices. The legal system moved from Spanish civil law to Anglo-American common law, and jury trials were introduced.

Still, echoes of the alcalde system persisted. The Texas county judge, with its blend of judicial and administrative powers, resembles the old alcalde in some respects. Similarly, justice of the peace courts took over many of the duties formerly held by alcaldes in local communities.

Other vestiges of Spanish law are seen in Texas’ family law code, judicial practices and procedures, and in water and land law.

Sources Cited

- Randell G. Tarín, “Leal Goraz, Juan,” in Handbook of Texas Online, Texas State Historical Association (1995). ↩︎

- Michael Ariens, Lone Star Law: A Legal History of Texas (Lubbock: Texas Tech University Press, 2011), pg. 5. ↩︎

- Ibid., pg. 5 ↩︎

- Joseph W. McKnight, Law Without Lawyers on the Hispano-Mexican Frontier, 66 West Texas Historical Association Year Book 51 (1990) ↩︎

- Jesús F. de la Teja and John Wheat, “Bexar: Profile of a Tejano Community,” The Southwestern Historical Quarterly 89, no. 1 (July 1985): 15. ↩︎

- James L. Haley and Marilyn P. Duncan, “The Law of Austin,” in Taming Texas: Law and the Texas Frontier (Austin: Texas Supreme Court Historical Society, 2018), pg. 22. ↩︎

- Ibid, pg. 24. ↩︎

📚 Curated Texas History Books

Dive deeper into this topic with these handpicked titles:

- Spanish Texas, 1519-1821

- Laws and Decrees of the State of Coahuila and Texas, in Spanish and English

Texapedia earns a commission from qualifying purchases. Earnings are used to support the ongoing work of maintaining and growing this encyclopedia.