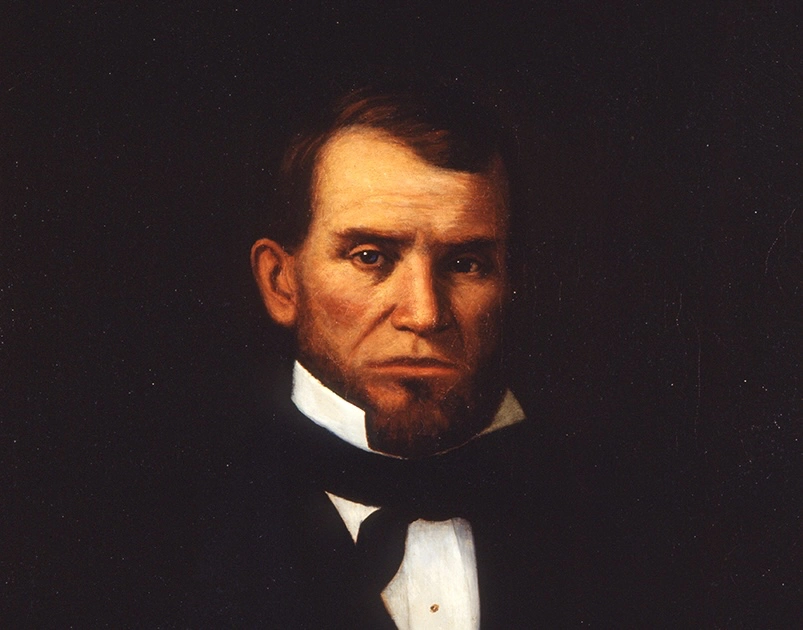

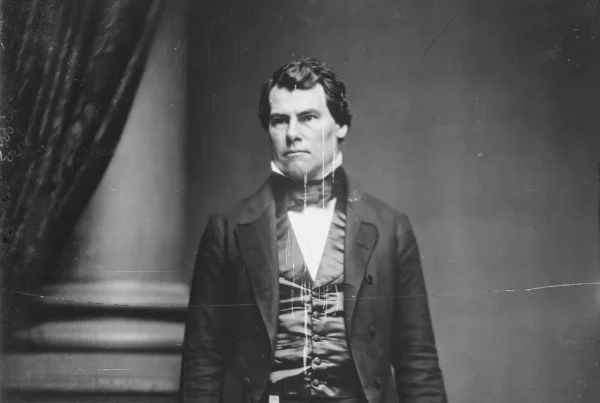

A member of the East Texas planter aristocracy, Hardin Richard Runnels (August 30, 1820 – December 25, 1873) served as the sixth governor of Texas, promoting militarization and secession in the lead-up to the U.S. Civil War.

Runnels is the only politician to have defeated Sam Houston in an electoral contest, soundly beating him in the governor’s race of 1857 before losing in a rematch two years later.

Later characterized as a “southern extremist” and “aggressive secessionist,” Runnels rode to office on a tide of Democratic Party strength. The party, formerly loosely organized, closed ranks in the late 1850s in response to the Republican Party’s ascent in the North and Midwest. In Texas, the Democratic Party at the time advocated for the defense of slavery and its expansion into western territories newly acquired in the Mexican-American War.

Early Life and Career

Runnels grew up in a wealthy family in Mississippi and moved to Texas in 1841 at the age of 21 or 22, shortly after the death of his father. He settled in Bowie County with his mother and two brothers and established a cotton plantation.

Within five years, Runnels won a seat in the Texas House of Representatives. He held this position through 1854, serving as Speaker in his final session. During this time, he grew in wealth, building and furnishing a Greek Revival mansion on his plantation, located near Old Boston, south of the Red River boundary between Texas and Arkansas.

In 1855, Runnels won election as lieutenant governor under Elisha Pease, who opted not to run for a third term in 1857. The state generally thrived during Pease’s term, and the outgoing governor made efforts to quell anti-unionist sentiment. By the time Pease left office, however, a spirit of national disunion was rising, and open violence had erupted in Kansas between pro-slavery and anti-slavery settlers, resulting in dozens of murders.

The Slave Trade and the Election of 1857

At the Texas Democratic Party Convention of 1857 (the first one) party leaders blocked the nomination of U.S. Senator and former President of the Republic Sam Houston. On the eighth ballot, party delegates chose Runnels as their nominee.

Houston responded by announcing an independent bid for governor, triggering a short but intense campaign pitting the 37-year-old secessionist against the 64-year-old unionist.

A key issue of the campaign—and of Southern politics generally at the time—was whether to reopen the African slave trade. Though slavery and the domestic slave trade were permitted throughout Texas and the South, the international slave trade had been illegal since 1808, under a law passed by the U.S. Congress prohibiting the importation of slaves.

This law followed on the heels of a similar law passed by the U.K. Parliament in 1807. The law technically applied only within the British Empire, but the Royal Navy zealously enforced it against slave ships of many nations, decimating the slavers’ international merchant fleet. Between 1808 and 1860, the Royal Navy’s West Africa Squadron captured an estimated 1,600 slave ships and freed 150,000 Africans. The U.S. Navy assisted in these efforts at times. By the 1850s, the trans-Atlantic slave trade had largely ceased. Slavers in Texas who wanted new slaves had to import them from elsewhere in the U.S., not from overseas.

These developments outraged Southern planters, who wanted the international trade resumed for both practical and symbolic reasons. Planters held commerce conventions yearly from 1856-1859, discussing ways to evade the Royal Navy blockade and lift the federal ban on the importing of slaves from Africa.

The topic was a popular one in Texas newspapers during the gubernatorial campaign of 1857. For example, Houston editor E.H. Cushing wrote a month before the election,

“We want labor… Let us replenish our fields with good, hearty, robust Negroes from the fountainhead. Let us take those black barbarians and make good christians of them—take care of them, and raise them to a level with our Negroes. The work is one of philanthropy and patriotism… only as slaves, can black labor be made useful, or the black race endurable on this soil.”1

The Houston Telegraph, edited by Cushing, wrote in its endorsement of Runnels:2

“Mr. Runnels is a Southern man in every sense of the word,—his highest ambition is to see the South quiet, prosperous and great—secure in all her rights, and the institution of slavery placed above the reach of its enemies…. He believes the institution of African slavery is warranted by the law of God, of man, and of nature and the necessities of mankind…”

As to Runnels’ opponent, Cushing wrote that he had “swallowed the heresies of anti-slavery men”:

“While we would not impugn the motives or tarnish the former fame of Gen. Houston, we dissent in toto from his position… and regard him as an untrue exponent of Southern sentiment and feeling upon it… I do not assert that Gen. Houston is really anti-slavery, but he is not vitally, practically pro-slavery,—he would concede, yield away, inch by inch those grounds upon which our ultimate rights, interests and prosperity—our expansion and national glory—must defend.”

In opposing the extension of slavery to new territories and seeking compromise with Northern free states, Houston was prioritizing the preservation of the Union and seeking to avoid a national confrontation.

Radicals like Runnels, on the other hand, believed that slavery should know no limits. In addition to supporting the trans-Atlantic slave trade and the expansion of slavery within U.S. western territories, Runnels supported a private military expedition (filibuster), which invaded Nicaragua in 1856 and set up a pro-slavery government there. In February 1857, shortly before he secured the Democratic nomination for governor, Runnels co-hosted a reception and ball in Galveston for Texan volunteers en route to Nicaragua.

On August 3, 1857, Runnels won the race against Houston by a vote of 32,552 (57.9%) to 23,628 (42.1%). Though still popular with voters as a hero of the Texas revolution, Houston had alienated the planter elite and the influential newspaper editors of the time by opposing the Kansas-Nebraska Act and arguing for the preservation of the Union.

Governorship

In his inaugural address, Runnels dwelt extensively on the question of slavery and called for “thorough military organization and training” in preparation for war with the North. “Prudence would dictate that our house should be set in order, and due preparation made for the crisis, that seems to be foreshadowed by coming events.”

Runnels demanded that Kansas be admitted to the Union as a slave state and warned that the South would be justified in seceding if this demand was not met. Throughout his term of office, he reiterated secessionist threats and demands of this kind.

Runnels implicitly insulted his defeated opponent, Sam Houston, and condemned his campaign as a “preconcerted design to distract and if possible to destroy the identity of the Democratic Party.” He accused Houston of reviving dangerous “Federalist” ideas—centralizing, nationalizing tendencies that undermined Southern autonomy.

Unlike Houston, who championed the permanence of the Union and the authority of the federal government, Runnels embraced a confederalist view of the Constitution: that the United States was a compact among sovereign states, binding only so long as its terms were faithfully upheld. If those conditions were violated, he believed, Texas and other states were justified in withdrawing their allegiance.

The protection and extension of slavery remained Runnels’ principal preoccupation throughout his time in office, though he also concerned himself with frontier security. He commissioned Colonel John “Rip” Ford as a commander of the Texas Rangers, directing him to quell raids led by Juan Cortina in the Rio Grande Valley.

During Runnels’ term, the Rangers fought a series of inconclusive battles against Cortina as well as Comanche and allied Indian tribes. Frontier violence was particularly bad in this era, contributing to Runnels’ electoral defeat by Sam Houston in a rematch on August 1, 1859.

Exploiting his hero status and unease with the new radical direction of the Democratic Party, Houston won 36,227 votes (56.8%) to Runnels’ 27,500 (43.1%)—a near exact reversal of the vote split of the prior election.

However, a key event occurred between the election and Runnels’ departure from office. In October 1859, radical abolitionist John Brown and 21 armed followers attacked a federal arsenal in Harper’s Ferry, Virginia, hoping to seize weapons and initiate a slave revolt. Though the attack failed (Brown and most of his followers were killed or captured), it stoked fears throughout the slaveholding South and accelerated the development of a militia system that would become the nucleus of the Confederate Army in the Civil War.

“The time has surely arrived when the South should look to her defenses.”

Runnels might well have won reelection if the Harper’s Ferry attack had occurred before the 1859 gubernatorial election. The abolitionist raid inflamed secessionist sentiment and polarized the national debate over secession and slavery, crowding out moderate voices. In his farewell address, Runnels returned to the theme of war, calling for “the organization of a militia in view of the impending sectional difficulties.” He said,

Civil War and Retirement

Runnels returned to his plantation after leaving office. According to the 1860 census, he owned 39 slaves. This placed him in the top 10% of slaveholders (the average number of slaves per slaveholder was around 7 to 8), though not among the ultra-wealthy.

Though he never held office again, Runnels participated in the 1861 Secession Convention. The outcome of the Civil War was, obviously, a disappointment to Runnels. A newspaper writer who knew him later reflected, “The utter destruction of his life-long aim and love, States Rights, by the chance of war, was a sad realization to Governor Runnels, and for several years he had remained quietly at home in attending to his private affairs.”3

During Reconstruction, Runnels participated in the 1866 Constitutional Convention, where he was among the “irreconcilables” who opposed federal Reconstruction and the extension of civil rights to freed slaves. He was elected as a vice president of the Texas Historical Society in 1870, its initial year in operation. He was also a member of St. John’s Masonic Lodge.

Runnels died on December 25, 1873, leaving behind no family, apart from three brothers in Bowie County. He had never married. He was buried in a family plot in Bowie County. Runnels’ remains were re-interred in a state cemetery in Austin in 1929.

Sources Cited

- The Weekly Telegraph (Houston), July 8, 1857, pg. 1. ↩︎

- The Weekly Telegraph (Houston), July 1, 1857, pg. 2. ↩︎

- “Death of Ex-Governor H.R. Runnels,” The Dallas Daily Herald, December 31, 1873, citing the Jefferson Tribune. ↩︎

📚 Curated Texas History Books

Dive deeper into this topic with these handpicked titles:

- Shifting Grounds: Nationalism and the American South, 1848-1865

- Colossal Ambitions: Confederate Planning for a Post–Civil War World

- The Texas Lowcountry: Slavery and Freedom on the Gulf Coast, 1822–1895

- A South Divided: Portraits of Dissent in the Confederacy

- This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War

Texapedia earns a commission from qualifying purchases. Earnings are used to support the ongoing work of maintaining and growing this encyclopedia.