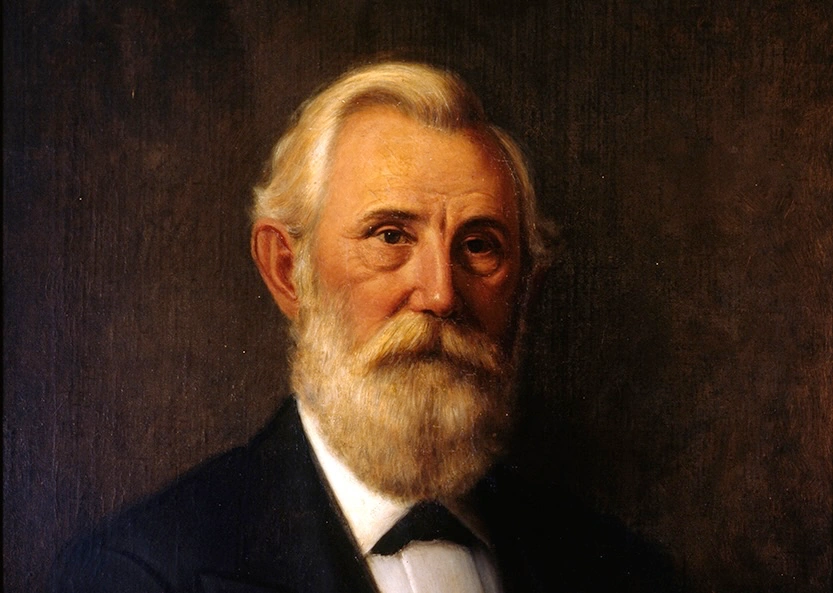

Oran Milo Roberts (1815–1898) was the third Democratic governor of Texas in the post-Reconstruction era, winning two elections and serving from 1879 to 1883. A former Confederate official and longtime judge, Roberts brought to the office a deeply legalistic mindset and a commitment to low-tax, limited-government principles that came to define the Democratic resurgence after Reconstruction.

Known as the architect of Texas’s “pay-as-you-go” fiscal policy, Roberts prioritized debt reduction and retrenchment at the expense of social services and infrastructure.

Early Life and Career

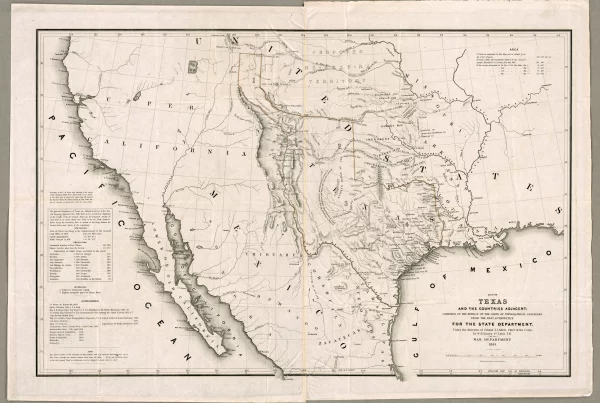

Roberts was born on July 9, 1815, in Laurens District, South Carolina. He studied law at the University of Alabama and began practicing in the 1830s. In 1841, he moved to Texas, then a fledgling republic, and soon established himself as a capable and ambitious legal professional. He served as district attorney and was elected to the Republic of Texas Senate in 1844.

Following annexation, Roberts’s career advanced rapidly. In 1856, he was appointed to the Texas Supreme Court, where he developed a reputation for strict constitutionalism and respect for state sovereignty. He was later named chief justice and held the post until the outbreak of the Civil War.

Secession and Confederate Service

An ardent supporter of Southern rights and slavery, Roberts played a leading role in Texas’s secession. In 1861, he presided over the Texas Secession Convention, earning him the nickname “the Old Alcalde” (a reference to the alcalde system of Mexican Texas). Under his leadership, the convention voted overwhelmingly to leave the Union, aligning Texas with the Confederacy.

During the Civil War, Roberts served as a colonel in the Confederate Army and later returned to judicial duties under the Confederate state government. After the Confederacy’s defeat, he was removed from office by military authorities and barred from holding public office during early Reconstruction.

Return to Public Life and the 1876 Constitution

As federal Reconstruction waned, Roberts reentered Texas politics. In 1874, he was reappointed to the Texas Supreme Court by the newly reestablished Democratic government. He played an influential role in the drafting and ratification of the Texas Constitution of 1876, a document designed to limit the power of the state and prevent the perceived excesses of Reconstruction-era centralization.

The 1876 Constitution—still the governing charter of Texas today (albeit since heavily amended)—reflected Roberts’s legal philosophy: decentralized authority, limited executive power, a plural executive branch, and restrictions on debt and taxation. These principles would later define his approach to the governorship.

Governorship: Retrenchment and Fiscal Conservatism

Roberts was elected governor in 1878 and inaugurated in 1879. He inherited a state still burdened by wartime debts and wary of federal intrusion. His administration’s most notable feature was the adoption of a strict “pay-as-you-go” fiscal policy: a strategy of cutting spending to balance the budget without incurring new debt.

To achieve this, Roberts slashed funding for state services, including public education, infrastructure development, and the penitentiary system. He argued that state government should live within its means and that any burdensome taxation would stifle recovery and infringe on local autonomy.

The policy was popular with rural voters and conservative Democrats but drew criticism from education advocates, urban leaders, and reformers who saw it as shortsighted. State institutions stagnated under budget constraints, and roads, schools, and hospitals fell into disrepair.

Nonetheless, Roberts’s administration succeeded in reducing the state’s bonded debt and reasserting fiscal discipline after the uncertainty of Reconstruction. His approach set a tone for state budgeting that persisted well into the twentieth century.

Education, Land Policy, and Railroad Regulation

Though skeptical of large-scale state spending, Roberts supported the permanent school fund and authorized land set-asides to support future educational institutions. During his term, the University of Texas was formally chartered (though it did not open until 1883), and Roberts took pride in laying its legal and financial foundation.

He also backed reforms to the General Land Office and the management of public lands, particularly in West Texas. Land policy during this era was marked by speculation, graft, and political favoritism. Roberts favored more transparent sales and surveys, though enforcement was often uneven.

On railroad issues, Roberts maintained a cautious stance. He supported regulation in principle but did little to strengthen the Railroad Commission or impose rate controls. His priority remained keeping government small and limiting interference in the private sector.

Later Years and Academic Career

Roberts declined to run for a third term in 1882 and was succeeded by John Ireland. After leaving office, he accepted a professorship in law at the newly established University of Texas and helped organize its law department. He lectured on constitutional law and Texas legal history and published several works on jurisprudence and civil government.

His academic career lasted until the mid-1890s, and he remained an influential figure in Texas legal circles until his death on May 19, 1898. He was buried in Oakwood Cemetery in Austin.

Legacy and Historical Assessment

As a jurist, Roberts was instrumental in shaping Texas constitutional law and advancing a conservative vision of a limited state. As governor, he imposed fiscal discipline and curbed government spending at a moment when institutional legitimacy was fragile. His rigid adherence to austerity arguably slowed the development of critical public services—especially education—in the postwar South.

He is remembered today more for his contributions to Texas legal institutions than for his political leadership. Leaders of the University of Texas School of Law historically regarded him as one of the school’s intellectual founders, and his writings on statecraft were widely read into the early 20th century.

In contrast to Reconstruction governors like Edmund J. Davis, who favored expansive government, or Progressives like Thomas Campbell, Roberts stands as a figure of legal traditionalism and retrenchment. His tenure reflects the ideological foundations of the post-Reconstruction Democratic consensus in Texas: decentralized power, low taxes, and cautious reform.