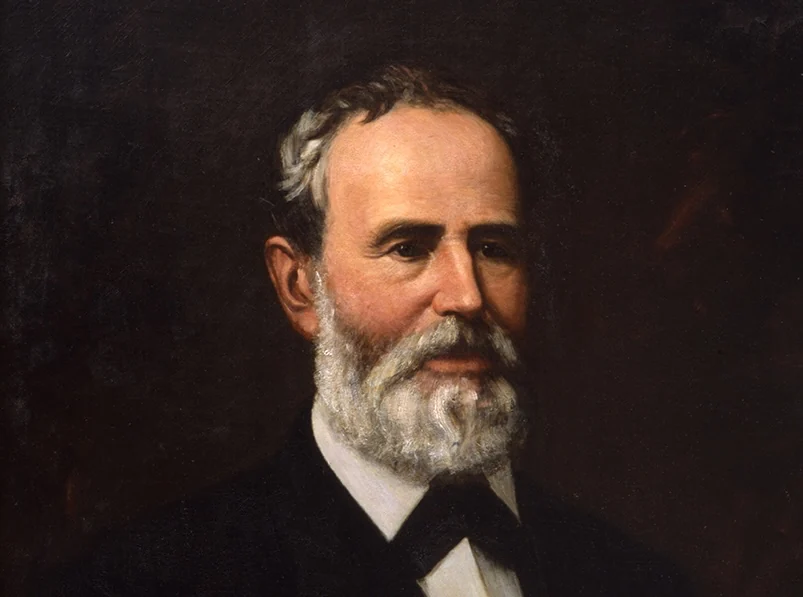

Elisha Marshall Pease (1812–1883) served as the fifth and thirteenth Governor of Texas, holding office from 1853 to 1857 and again from 1867 to 1869 under federal appointment. A New England-born lawyer who had emigrated to Texas in his 20s, Pease helped lay the fiscal and administrative foundations of Texas during its formative years.

His final term as governor occurred in the aftermath of the Civil War, an era of economic hardship and growing lawlessness. Pease alienated both the secessionists and radical Reconstructionists and resigned toward the end of his term after disagreements with General Joseph Jones Reynolds, commander of the Department of Texas.

Early Life and Legal Career

Pease was born on January 3, 1812, in Enfield, Connecticut. He migrated to Mexican Texas in 1835 at the age of twenty-three and soon became involved in the political and legal upheavals that defined the period. After briefly returning to the United States during the Texas Revolution, he returned to the new Republic and studied law under prominent attorney William B. Ochiltree. Pease was admitted to the bar in 1837 and quickly established himself in Brazoria County, where he built a reputation for legal acumen and political reliability.

His early career included appointments as district attorney and secretary of the Senate in the Republic of Texas. In 1846, following statehood, he was elected to the First Texas Legislature and played a key role in drafting and codifying state laws.

Fiscal Conservatism and Administrative Reform

Pease’s two elected terms as governor, from 1853 to 1857, came during a period of rapid growth and increasing sectional tension. A committed Democrat and fiscal conservative, Pease prioritized reducing the state’s public debt—a lingering burden from the days of the Republic. He achieved this through a combination of sound budgeting, surplus revenues from land sales, and strict controls on state spending.

Governor Pease was also an early advocate of state-sponsored education. During his tenure, Texas saw the first meaningful steps toward the establishment of a public school system, with legislative support for the creation of school districts and the allocation of public lands to support permanent school funding. Although the results were uneven, Pease’s efforts laid the groundwork for future expansion of public education in the state.

He also emphasized improvements in transportation infrastructure, supporting investment in railroads and internal improvements at a time when Texas was still largely isolated from national markets. These initiatives helped attract investment and migration into central and eastern Texas, although critics accused Pease of favoring elite interests.

Compared to the earlier Republican era, the four years of Pease’s governorship in the 1850s were stable and prosperous, even as a national crisis loomed over slavery and secession. A textbook used in Texas schools later that century stated, “Pease’s administrations were marked by the progress and prosperity of the state. Immigrants came from all parts of North America and Europe; towns sprang into existence; public buildings were erected, crops flourished, trade increased, and the people began to gather about them many of the luxuries as well as the comforts of the older States.”1

Pease declined to seek a third consecutive term in 1857 and was succeeded by his political rival, Hardin Runnels. He returned to legal practice and remained engaged in public life, quietly opposing the growing momentum toward secession in the 1850s.

Civil War and Unionist Alignment

Although Pease owned slaves, he strongly opposed secession. In 1861, he was among a minority of Texas delegates who voted against leaving the Union. Once the state seceded, however, he retired from public affairs and largely withdrew from political life during the Civil War.

His Unionist sympathies reemerged after the Confederacy’s defeat. In 1866, he attended the state constitutional convention and supported lenient reintegration measures—emphasizing the restoration of civil government, economic recovery, and basic rights for freedmen, though not full political equality.

Provisional Governorship and Reconstruction Tensions

In 1867, following the imposition of Congressional Reconstruction and the removal of Governor Throckmorton, General Philip H. Sheridan appointed Pease as provisional governor of Texas. Though previously a political moderate, Pease now supported federal enforcement of Reconstruction laws and worked to implement new civil and political rights for African Americans under military supervision.

His administration was constrained by conflict between civilian authorities, the military command, and factions within the Republican Party. Pease attempted to navigate these tensions while restoring basic state functions—supervising local elections, reorganizing law enforcement, and supporting the drafting of the 1869 Texas Constitution.

Frustrated by his lack of real authority and the frequent intervention of federal military officials, Pease resigned in 1869. His departure underscored the deep divisions within the Reconstruction coalition and the unstable balance between federal oversight and local governance.

Later Years and Legacy

Pease returned to private life in Austin, where he continued to advocate for fiscal prudence and civic improvement. He remained active in civic life and supported the growth of public institutions well into his later years. He died on August 26, 1883, and was buried in Oakwood Cemetery in Austin.

Though never a charismatic politician or popular campaigner, Pease left an enduring mark on Texas’s institutional development. He helped shape early legal codes, balanced the state’s finances, and introduced a framework for public education at a time when few Southern leaders prioritized such efforts.

Pease’s Reconstruction-era service tainted his reputation among both Republicans and Democrats, but he was soon forgotten as his successor, Edmund J. Davis, assumed wide-ranging powers and became a much more polarizing figure. In contrast to Pease, Davis would long be remembered—and villainized as a tyrant—during the Jim Crow era.

- Percy V. Pennybacker, A New History of Texas for Schools: Also for General Reading and for Teachers Preparing Themselves for Examination, Revised ed. (Palestine, TX: Percy V. Pennybacker, 1895), 258 ↩︎