In the closing years of the 19th century, the Populist Party—also known as the People’s Party—emerged as a formidable force in Texas politics, drawing support from struggling farmers, laborers, and reform-minded citizens disillusioned by the two dominant parties.

Fueled by economic hardship and a growing distrust of monopolistic corporations, the movement surged with promises of land reform, railroad regulation, and more direct democracy, including the direct election of senators, who were chosen by state legislatures until the ratification of the Seventeenth Amendment in 1913.

Though the Populists never gained lasting control in Texas or nationally, their brief ascendancy in the 1890s left a profound mark on the political landscape and helped usher in many reforms later adopted by the Progressive Era.

Roots of Discontent

Texas in the late 19th century was overwhelmingly rural, and agriculture dominated the state’s economy. Falling cotton prices, burdensome debt, predatory railroad practices, and the tight grip of Eastern financiers created a volatile mix of resentment and desperation among small farmers. The existing Democratic establishment, closely aligned with business interests, offered little relief.

The roots of the Populist movement can be traced to the rise of farmers’ alliances in the 1870s and 1880s. The Texas Farmers’ Alliance, headquartered in Waco, became one of the most organized and influential. Its leaders preached cooperative buying and selling, political education, and solidarity across class lines. By the late 1880s, it had grown into a national force, helping to found the National Farmers’ Alliance and Industrial Union. However, frustrated by the failure of the major parties to adopt their platform, alliance leaders called for direct political action.

The Birth of the Populist Party

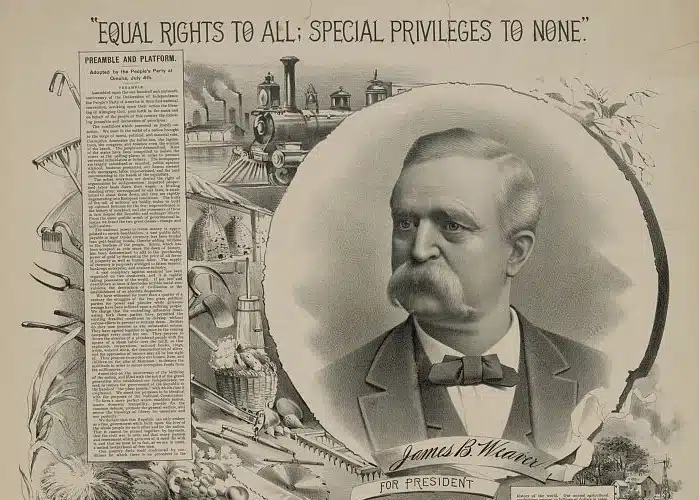

In 1891, activists gathered in Cincinnati to form the People’s Party, with the aim of challenging the status quo through electoral means. Their national platform, adopted in Omaha in 1892, was a bold call for sweeping reforms: free coinage of silver, a graduated income tax, government ownership of railroads and telegraphs, and the direct election of U.S. senators.

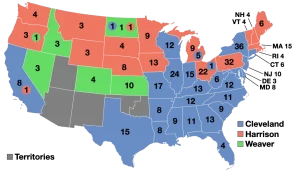

Texas Populists quickly mobilized. The state party drew from both white and Black farmers—though always uneasily—and found support among debt-ridden tenants, impoverished homesteaders, and urban laborers. In the 1892 election, the Texas People’s Party captured over 20 percent of the statewide vote, and James Weaver, the Populist candidate for president, won more than one million votes nationwide—carrying five western states.

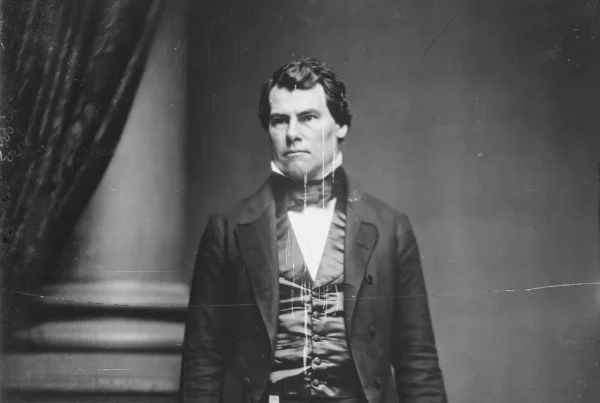

One of the party’s most compelling leaders in Texas was Thomas L. Nugent, a former Confederate soldier and judge. Nugent ran for governor as a Populist in 1892 and again in 1894, finishing second both times. His candidacy helped the Populists gain momentum, winning several seats in the state legislature and controlling local governments in parts of North and East Texas.

Black Leadership and Bi-Racial Organizing

Despite the limitations of the era, African American Texans were not just participants but often leaders in the Populist movement. The Colored Farmers’ Alliance, founded in Texas in 1886, became the largest Black agrarian organization in the nation, with over a million members at its peak. From this base emerged leaders such as Rev. Henry J. Jennings, a longtime activist who was elected to the state Populist executive committee in 1891. Jennings organized “colored clubs” and traveled across Texas counties rallying Black farmers to the cause.

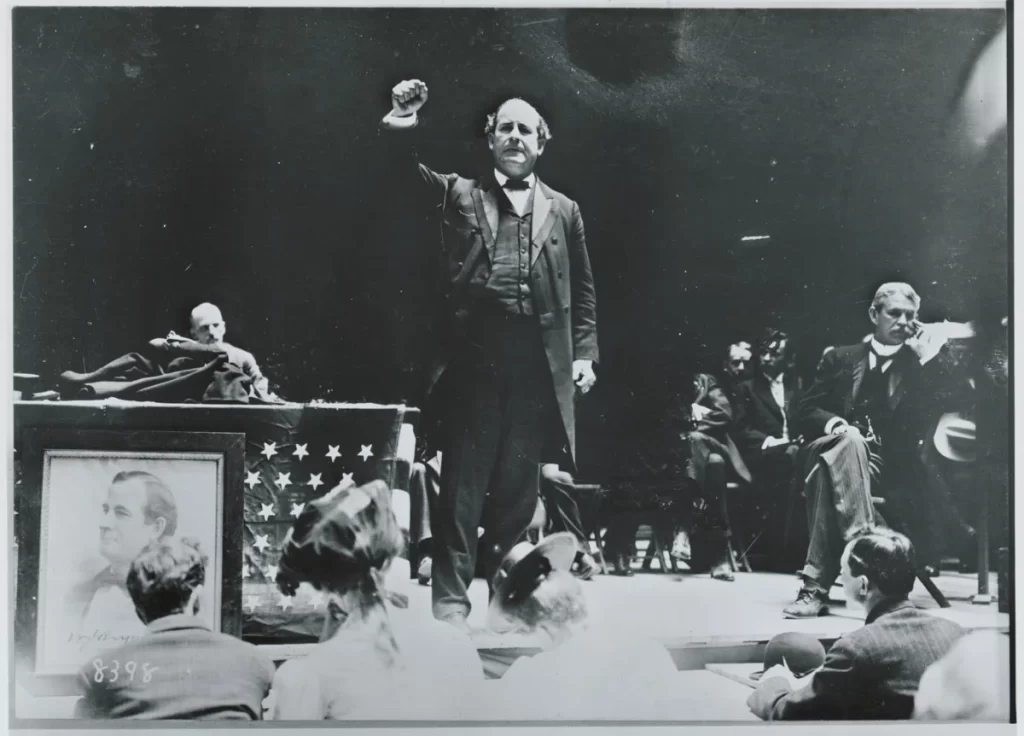

Another key figure was John B. Rayner, a gifted orator and political organizer. A former Republican who shifted allegiance to the Populist movement, Rayner was appointed to the state Populist platform committee and helped enroll tens of thousands of Black voters into the party’s ranks. He spoke at major Populist gatherings, advocating for civil rights, agrarian reform, and equal political representation.

This fragile biracial coalition reflected one of the most radical experiments in Southern politics since Reconstruction. But it also attracted intense resistance. White Democrats warned of “Negro rule” to rally white voters and resorted to fraud, intimidation, and poll taxes to drive down Black turnout. By the late 1890s, Populists were increasingly torn between their egalitarian ideals and the pressures of white supremacy.

The Limits of Fusion

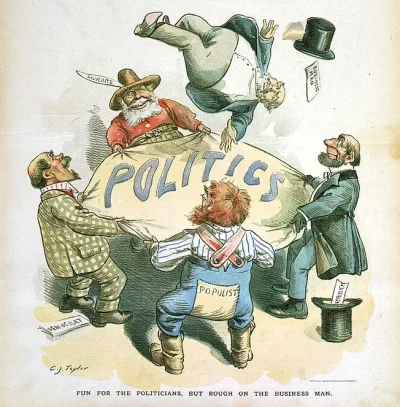

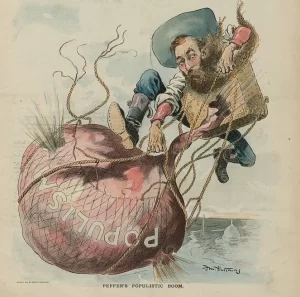

By the 1896 election, Populist leaders faced a strategic dilemma: maintain independence or support William Jennings Bryan, the Democratic nominee whose “free silver” platform echoed many Populist demands. The national Populist Party ultimately endorsed Bryan in a controversial act of fusion politics. In Texas, fusion was even more divisive. Many Populists feared that aligning with Democrats would dilute their identity and betray the movement’s principles.

Though Bryan lost the presidency to Republican William McKinley, the 1896 campaign marked the high-water mark of Populist influence. In Texas, the fusion effort failed to unseat the Democratic machine, which had mastered the tools of patronage, voter suppression, and election manipulation. In the years that followed, Populist ranks thinned, and internal divisions deepened.

National Movement, Local Struggles

While Texas was a major base of Populist activity, the movement had notable strength in other parts of the South and Midwest. In Kansas, Populists briefly captured the state legislature and governorship. In North Carolina, a fusion alliance between Populists and Republicans gained power in the 1890s, prompting a harsh Democratic backlash that culminated in the Wilmington Insurrection of 1898, one of the only successful coups in U.S. history.

In the West, Populists gained influence in Colorado, Idaho, and Nevada—states sympathetic to silver coinage and hostile to railroad monopolies. But across the country, entrenched party loyalties made sustained populist coalitions difficult to maintain.

Decline and Legacy

The unraveling of the Populist Party began almost as soon as it reached its peak. The 1896 decision to endorse Democratic presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan—a move intended to unite reform forces under a common banner—marked a turning point. While Bryan’s “free silver” platform aligned with Populist goals, the fusion with the Democrats came at a steep cost: it blurred the party’s distinct identity, alienated some of its core supporters, and allowed the Democratic establishment to reassert control in Southern states like Texas. Many Populists viewed the alliance as a betrayal of their founding principle: political independence from the two major parties.

At the same time, the movement was under siege from outside. In Texas and across the South, Democratic officials responded to the Populist challenge with aggressive countermeasures, combining patronage networks with open voter suppression. The imposition of the poll tax in Texas in 1902 disenfranchised thousands of poor voters, particularly African Americans and tenant farmers—two groups that had formed the backbone of Populist support. Literacy tests, white primaries, and intimidation campaigns further eroded the fragile cross-racial alliances that had given the movement its moral and electoral force.

The decline of the Populist movement coincided with the rise of Jim Crow laws throughout the South, which codified racial segregation. Efforts at biracial coalition-building faced growing resistance as Southern states, including Texas, moved quickly to enforce separation of the races and suppress Black political participation.

Organizational fatigue also set in. Lacking the institutional depth of the major parties, the People’s Party depended heavily on local networks, activist newspapers, and volunteer clubs. As defeats mounted and the fusion controversy deepened internal rifts, many county and precinct-level organizations began to wither. Populist newspapers folded, funding dried up, and party leaders increasingly drifted in separate directions—some toward Bryanite Democrats, others toward socialism or back into local activism.

The national context also changed. Economic conditions improved in the early 1900s, dulling the sense of urgency that had once driven the movement. At the same time, many of the reforms Populists had long advocated—railroad regulation, trust-busting, the direct election of senators, and a federal income tax—were gradually taken up by the Progressive movement within the two major parties. Even as the Populist Party dissolved, its ideas gained traction on the national stage.

Lasting Legacy

In Texas, former Populists gradually filtered back into the Democratic Party, bringing with them a reformist impulse that helped shape state policy on education, regulation, and public finance in the early 20th century. Some held onto the cooperative ideals and agrarian advocacy of the Farmers’ Alliance era, influencing local and state-level politics even after the party itself vanished from the ballot.

Ultimately, the failure of the Populist Party to establish a lasting third-party alternative reflected the structural barriers that continue to define American politics. The first-past-the-post electoral system, rigid party loyalty, and regional divisions combined to make sustained third-party success extraordinarily difficult.

Although the Populist Party did not survive as a lasting political organization, many of its core proposals were later adopted in modified form during the Progressive Era. Its platform—centered on direct democracy, economic regulation, and public oversight—helped influence broader reform efforts at both the state and national levels. In Texas, the movement’s brief presence contributed to ongoing debates over taxation, corporate regulation, and electoral reform, leaving an institutional and rhetorical legacy that shaped early 20th-century policymaking despite the party’s organizational collapse.