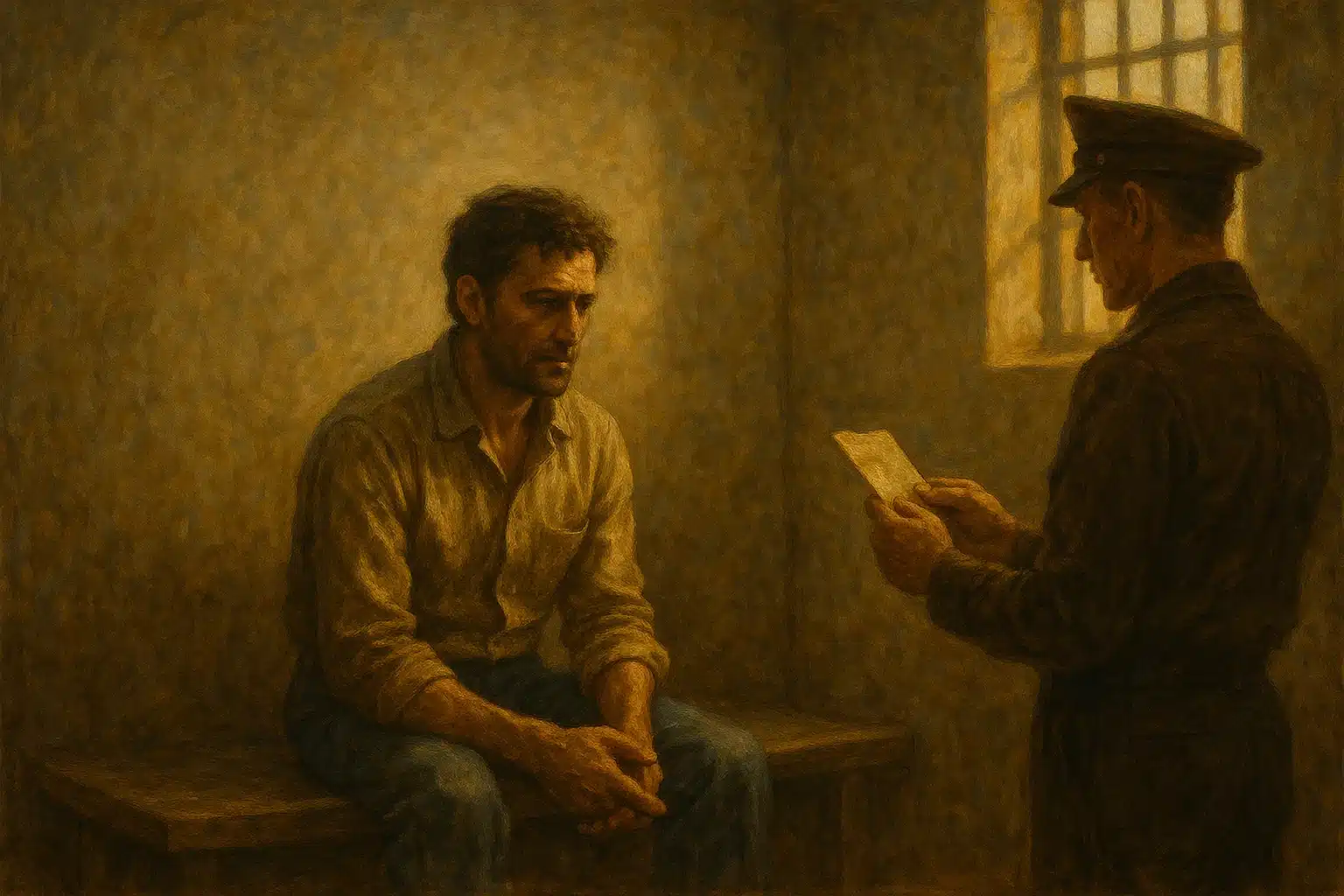

If you’ve ever watched a crime drama, you’ve probably heard the words: “You have the right to remain silent.” That’s part of what’s called the “Miranda warning,” and it comes from one of the most important Supreme Court cases in U.S. history: Miranda v. Arizona (1966). This case changed how police across the country—and in Texas—must handle arrests and interrogations. Today, understanding the Miranda decision is essential for anyone studying criminal justice or Texas law.

Miranda v. Arizona

In 1963, a man named Ernesto Miranda was arrested in Phoenix, Arizona, for kidnapping and rape. After two hours of police questioning, he signed a written confession. But here’s the issue: he was never told that he had the right to remain silent, or that he could ask for a lawyer. Miranda’s defense argued that his confession shouldn’t count, because he hadn’t been properly informed of his rights.

The U.S. Supreme Court agreed. In a narrow 5–4 decision, the Court held that suspects in police custody must be clearly informed of their constitutional rights before any custodial interrogation begins. The ruling was based on two key provisions of the U.S. Constitution.

First, the Fifth Amendment guarantees that no person “shall be compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself.” This means that individuals have a right to remain silent and cannot be forced to confess or answer questions that might incriminate them. The Court recognized that police interrogations, especially when conducted in isolation and under pressure, could easily coerce individuals into giving up that right—unless they were first told they had it and knowingly chose to waive it.

Second, the Sixth Amendment provides that “in all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right… to have the assistance of counsel for his defense.” The Court extended this protection to include the right to consult with a lawyer during police questioning, not just at trial. If a person cannot afford an attorney, the state must provide one.

Together, these amendments form the constitutional foundation of the Miranda warning. The Court’s decision in Miranda v. Arizona emphasized that these rights are not just theoretical—they must be actively protected by law enforcement through clear and timely warnings. Otherwise, any statements obtained during questioning may violate the Constitution and must be excluded from evidence in court.

What Are the Miranda Rights?

The standard Miranda warning goes something like this:

- You have the right to remain silent.

- Anything you say can and will be used against you in a court of law.

- You have the right to an attorney.

- If you cannot afford an attorney, one will be provided for you.

- You have the right to terminate the interview at any time.

Although the exact wording may vary slightly by state or police department, the meaning must be clear. Police must make sure suspects understand these rights and voluntarily give them up before questioning begins.

How Does Miranda Apply in Texas?

In Texas, the Miranda ruling is directly followed, just like in other states. But Texas law also adds some additional protections and procedures, especially when it comes to written or recorded confessions.

Under Texas Code of Criminal Procedure Article 38.22, no written or recorded confession is admissible in court unless the suspect was given the Miranda warnings beforehand—and waived those rights knowingly, intelligently, and voluntarily. For confessions to be valid, Texas law requires:

- Clear warning of rights: The person must be informed of their right to remain silent, their right to an attorney, and the risk that anything they say can be used against them.

- A recorded waiver: The suspect must clearly agree to talk after hearing the warnings.

- Proper recording: In most cases, custodial interrogations that lead to confessions must be electronically recorded to be admissible in court.

This helps ensure that confessions aren’t forced or misunderstood. If an officer fails to properly give the warnings or record the waiver, the confession could be suppressed—or kept out of evidence—at trial.

Common Misunderstandings

Many people think that police must read the Miranda rights the moment someone is arrested, but that’s not quite true. The warnings are only required when:

- A person is in custody (not free to leave), and

- The police want to interrogate them (ask questions likely to produce incriminating responses).

If you’re just being questioned on the street or during a traffic stop, Miranda usually doesn’t apply. But if you’re handcuffed and taken to a police station for questioning, the warning is required before any interrogation begins.

Why Miranda Still Matters in Texas

Miranda v. Arizona remains one of the strongest protections for individual rights in the American criminal justice system. In Texas, where law enforcement powers are often emphasized, Miranda plays a key role in balancing police authority with constitutional rights.

For example:

- If a Texas officer questions a suspect in custody without giving a Miranda warning, the prosecution can’t use the confession in court.

- If someone confesses after being warned, but later claims they didn’t understand their rights, the judge may hold a hearing to decide if the confession is admissible.

- Defense attorneys in Texas routinely file motions to suppress evidence based on Miranda violations—challenging the way a confession was obtained.

In short, Miranda helps ensure that confessions are voluntary, not coerced. It also teaches police officers to follow strict procedures, which helps protect both the rights of suspects and the integrity of the criminal justice system.

So next time you hear “You have the right to remain silent,” remember: it’s not just a TV catchphrase. It’s a constitutional safeguard, backed by decades of law, and it matters in every Texas courtroom.