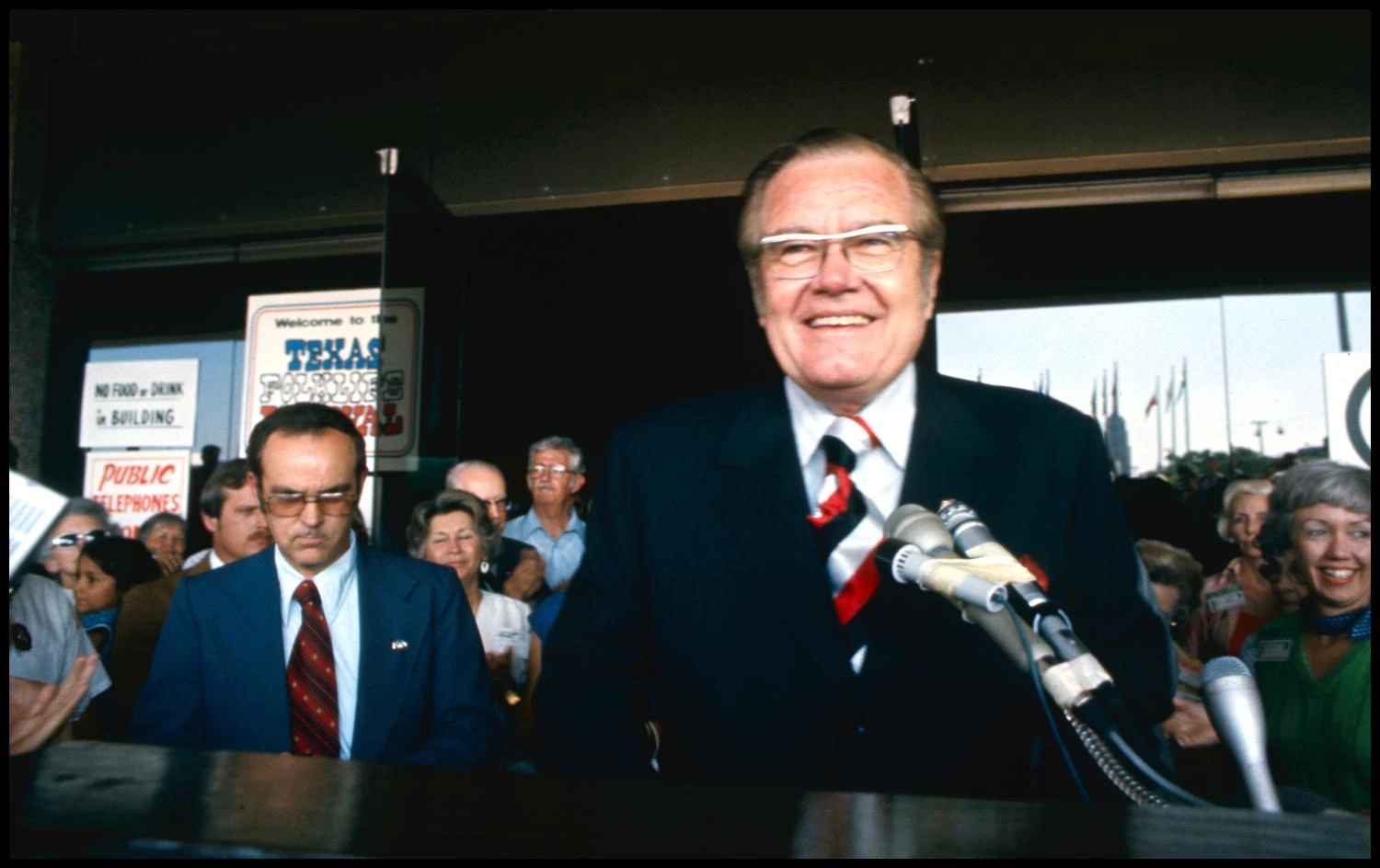

Dolph Briscoe Jr., who served as governor of Texas from 1973 to 1979, was a conservative Democrat and the last figure to lead the state from within its old rural Democratic tradition. A South Texas rancher with deep roots in the landowning class, Briscoe governed with quiet restraint and embodied the values of a party shaped more by geography and class than by ideology.

He emerged in the wake of scandal and infighting to restore stability and public trust—offering Texans a style of leadership rooted in local control, institutional caution, and pragmatic conservatism. In retrospect, Briscoe’s tenure closed a chapter that began in the days of one-party rule and ended just as a modern, urbanizing Texas began to take political shape.

A Party Divided: Scandal and Factional Breakdown

By the early 1970s, the Texas Democratic Party had begun to crack under the weight of its own dominance. Though still virtually unchallenged in statewide elections, Democrats were increasingly split between rural conservatives—often older, White, and economically traditionalist—and a rising bloc of urban liberals pushing for civil rights, expanded social programs, and institutional reform.

These tensions were no longer just ideological—they became visible in policy failure and political scandal. The first major rupture came with the Sharpstown scandal in 1971, which exposed a stock fraud scheme involving high-ranking Democrats, including Governor Preston Smith and House Speaker Gus Mutscher. The fallout was swift: voters ousted dozens of legislators in the 1972 elections, and the party’s reputation for ethical leadership was deeply damaged.

Then, in 1974, Democrats suffered another blow with the collapse of a constitutional convention designed to modernize the Texas Constitution of 1876. Despite commanding a legislative majority and broad public support at the outset, the convention failed due to infighting, lobbying pressure, and an inability to bridge divides between liberals and conservatives. Reform-minded Democrats had promised modernization but delivered gridlock.

Into this fractured environment stepped Dolph Briscoe. Lacking the ideological zeal of either faction, Briscoe presented himself as a clean, conservative alternative—someone who could stabilize state government and restore its credibility without igniting further partisan wars. His victory in the 1972 Democratic primary, followed by an easy general election win, signaled voters’ preference for steady leadership over visionary upheaval.

Policy and Priorities

Briscoe’s record as governor reflects his temperament: pragmatic, incremental, and fiscally cautious. Though not a reformer in the activist sense, he did sign major legislation aimed at restoring transparency and accountability in the wake of Sharpstown. During his governorship, the state implemented new financial disclosure laws and ethics rules for state officials—reforms that, while modest, addressed the immediate credibility crisis.

Briscoe’s strongest policy focus was on infrastructure, particularly roads and water systems. A former state highway commissioner and rural representative, he prioritized funding for farm-to-market roads and supported regional water planning efforts. He also advocated for increased state investment in public education, particularly in underserved rural districts, without raising taxes.

Relationship with the Legislature

Briscoe’s cautious approach frustrated some fellow Democrats. His critics characterized him as indecisive and disengaged. For example, State Senator Grant Jones (D-Abilene) said, “I was very fond of Governor Briscoe, but it’s extremely difficult to work for a person who’s in a position of leadership that has difficulty making a decision. That was Mr. Briscoe’s biggest problem. I don’t know whether he simply didn’t understand the issues or whether he was simply unwilling to make final decisions that would have to be made.”1

Similarly, a member of the opposition party at the time, Fred Agnich (R-Dallas), described Briscoe as inaccessible: “It’s common knowledge that it was awfully hard to get to see Dolph Briscoe. The Democrats in the Legislature had an awful time. I fared somewhat better than they did simply because Janie Briscoe and I had become good friends. If I wanted to see Dolph, I usually called up Janie and would come over, and she’d fix me a cup of coffee. It didn’t matter much who was in the office, why, I got in… He most certainly did not spend any time cultivating any sort of relationship with the Legislature.”2

At the time, the Legislature included numerous freshmen, including lawmakers focused on ethics, transparency, and structural reforms, in response to the Sharpstown scandal. Their most ambitious project was the 1974 constitutional convention, a wholesale rewrite of the constitution of 1876. The convention narrowly failed to pass the draft constitution.

Jones, the senator from Abiline, faulted Briscoe in part for this, saying that the governor had stayed aloof from the process until unexpectedly coming out against the new constitutional proposal: “I felt like he didn’t play fairly with the Constitutional Convention, because I left that convention convinced that we had responded favorably to every recommendation Mr. Briscoe made.”

“Then, after it was over, for him to come out in blanket opposition to the constitutional proposal is to me bordering on irresponsibility… If you had an opportunity to be involved in a decision-making process and don’t take that opportunity, then you ought to be quiet… (and not) criticize that which is finally decided.”

Similarly, Paul Burka, the long-time editor of Texas Monthly, criticized Briscoe for his indecision and aloofness: “His administration was remarkable for its lack of initiatives… (This) is my personal memory of the Briscoe years: Nothing happened. The governor was irrelevant. The political life of the state went on without him.”3

Nonetheless, Briscoe’s caution and conservatism resonated with large swaths of the electorate who were weary of scandal and skeptical of big government. Briscoe defeated liberal Frances “Sissy” Farenthold in the 1974 Democratic primary election, taking 67% of the votes compared to her 28%, before sailing to an easy win in the general election against Republican Jim Granberry, securing a second term.

Notably, Briscoe served two years under his first term, and four years under his second term, as a result of a constitutional amendment approved by voters in 1972, which extended the governor’s term from two to four years. Before Briscoe, only Governor Edmund J. Davis (1870-1874) had served a four-year term, under the Reconstruction constitution of 1869.

Race Relations and Desegregation

Briscoe’s governorship coincided with the continued implementation of federal desegregation orders across Texas school districts. While the legal foundations for integration had been laid in the 1950s and ’60s, the practical realities of busing, redistricting, and federal oversight intensified in the 1970s.

Briscoe approached these issues with restraint, reflecting both his conservative instincts and his rural constituency’s preference for local control. He generally avoided direct intervention in school integration debates, deferring to courts and school boards. This hands-off posture drew criticism from civil rights advocates who believed stronger state-level leadership was needed to ensure compliance and equity. Yet it also allowed Briscoe to maintain broad political support during a volatile period, sidestepping the confrontational rhetoric that had defined earlier conflicts over race.

While Briscoe did not champion civil rights causes, neither did he roll back the gains of earlier years. His approach to race and integration was emblematic of his broader political style: cautious, deferential, and focused on preserving institutional stability during a time of social change.

The Realignment Begins: Republican Momentum

Though Briscoe won re-election in 1974 by a wide margin, his second term took place in a shifting political landscape. Nationally, the Southern realignment was accelerating, with conservative voters—especially White, rural, and business-oriented Texans—drifting toward the Republican Party. The post–civil rights era had scrambled partisan loyalties, and economic concerns were making tax policy and deregulation more salient than New Deal-style populism.

In Texas, this realignment began to show itself clearly in 1978, when Briscoe sought a third term. Despite incumbency and name recognition, he lost the Democratic primary to Attorney General John Hill—a sign that even within his own party, Briscoe’s cautious, conservative style was falling out of step. Hill would go on to lose to Republican Bill Clements, marking the first Republican gubernatorial victory in over a century.

Briscoe’s defeat and Clements’ victory were pivotal. While Democrats would continue to win some statewide races into the 1980s and 1990s, the ideological balance had shifted. The conservative Democrat—the archetype that had once ruled Texas—was quickly becoming politically obsolete. While later Democrats like Mark White would carry some conservative or centrist policy positions, Briscoe is often seen as the last to embody Texas’s older rural Democratic style—a politics shaped more by land, locality, and traditional institutions than by national ideological trends.

Early Life and Path to Power

Dolph Briscoe Jr. was born in 1923 in Uvalde, Texas, into a family of ranchers and landowners. He graduated from the University of Texas at Austin and served as a captain in the U.S. Army during World War II. Upon returning home, he entered state politics and won election to the Texas House of Representatives in 1948, where he served for nearly a decade.

Briscoe left elective politics for a time to manage his family’s extensive ranching operations, becoming one of the largest individual landowners in Texas. In the late 1960s, amid rising dissatisfaction with state government, he returned to public life. After losing the 1968 gubernatorial primary, he ran again in 1972—this time benefiting from the wave of anti-corruption sentiment triggered by Sharpstown. His clean reputation and deep rural connections helped him consolidate support across the ideological spectrum.

Later Life

After his political career ended, Briscoe largely retreated from public life but remained active as a philanthropist and civic leader. He was owner of the First State Bank of Uvalde. With holdings of more than 600,000 acres, he was also the largest individual landowner in Texas.

He contributed generously to educational institutions, historical preservation efforts, and public libraries. The Dolph Briscoe Center for American History at the University of Texas, which he generously endowed, bears his name. Briscoe died in 2010 at the age of 87.

Twilight of a Tradition

Dolph Briscoe governed during the twilight of conservative Democratic rule in Texas. In the aftermath of scandal and ideological drift, he offered a restrained, pragmatic vision rooted in rural values and institutional stability. But the forces reshaping Texas politics—partisan polarization, suburban growth, and national conservative ascendancy—were already in motion. Briscoe did not stop the realignment, but he slowed it just long enough to write the final chapter of an era now closed.

- Senator Grant Jones, interview by North Texas State University Oral History Collection, no. 490, August 21, 1979, pg. 24. ↩︎

- Representative Fred Agnich, interview by North Texas State University Oral History Collect, no. 492, November 30, 1979, pg. 7-8. ↩︎

- Paul Burka, “Dolph Briscoe, R.I.P.,” Texas Monthly, June 28, 2010. ↩︎