When Texans declared independence from Mexico in 1836, they needed more than just a flag or an army—they needed a government. The site they chose for that momentous act was a modest frontier town called Washington-on-the-Brazos. For a brief but pivotal period, it served as the first capital of the Republic of Texas. Though quickly abandoned in the chaos of war, its symbolic significance remains unmatched. It was here that the revolution became a republic.

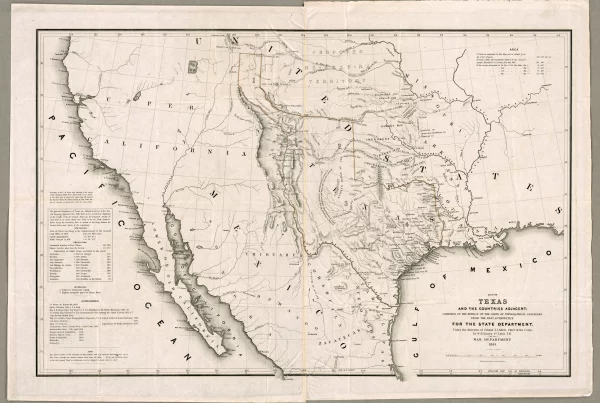

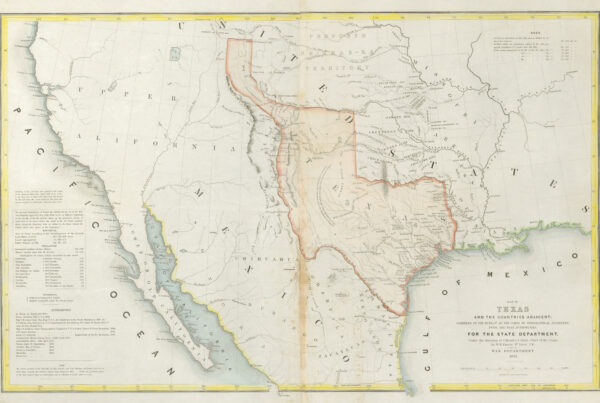

Located in present-day Washington County along the Brazos River, the town of Washington had grown in the early 1830s as a trading post and river port for Anglo-American settlers. It lay on the edge of the Austin colony, in a region increasingly defined by its cultural distance from central Mexico. When delegates gathered here in the spring of 1836, they did so with a mix of defiance and urgency. Mexico’s federal system had collapsed under President Santa Anna’s dictatorship, and open rebellion was already underway across Texas and other parts of Mexico.

The Convention of 1836 convened on March 1 in a rough wooden hall, just days before the fall of the Alamo. Fifty-nine delegates—most of them recent arrivals from the American South—assembled to decide Texas’s fate. Within days, they adopted a Declaration of Independence and set about drafting a constitution. The convention also formed an interim government, naming David G. Burnet as president and Lorenzo de Zavala as vice president of the new republic.

Washington-on-the-Brazos was never intended to be a permanent seat of government. It was chosen for its relative centrality and accessibility, but also for the simple reason that it was one of the few towns with enough infrastructure to host the convention. Even so, conditions were crude. The delegates worked in a drafty structure, seated on planks balanced atop whiskey barrels. Outside, the threat of war was becoming more immediate by the hour.

On March 6, while the convention was still underway, the Alamo fell. Santa Anna’s forces began a rapid eastward march. News of the advancing army reached Washington-on-the-Brazos, prompting a hurried evacuation. The convention concluded on March 17, and the provisional government fled east in what became known as the “Runaway Scrape”—a chaotic retreat of civilians and leaders attempting to stay ahead of Mexican troops. With that, Washington-on-the-Brazos ceased to function as the capital.

The next several months saw the Republic’s government on the move. It relocated to Harrisburg, which was soon burned by Mexican forces, then to Galveston Island, Velasco, and Columbia. In 1837, the capital moved to the new city of Houston, founded near the site of the Texan victory at San Jacinto. Finally, in 1839, the Republic chose Austin as its permanent capital—a decision that solidified central Texas as the political heart of the state.

Although Washington-on-the-Brazos served as capital for less than a month, its legacy far exceeds its brief tenure. It was the birthplace of the Republic and the site of foundational documents that defined Texas’s political identity for decades. Today, the town is preserved as the Washington-on-the-Brazos State Historic Site. Visitors can walk the grounds of Independence Hall, view a replica of the original convention hall, and learn about the dramatic events of 1836 through museum exhibits and reenactments.

In the larger story of Texas, Washington-on-the-Brazos stands as a place of vision and vulnerability. It was a temporary capital in a time of instability, chosen not for its grandeur but for its availability. Yet within its wooden walls, the foundation of Texas was laid. For Texans, it remains a sacred site—a reminder that from disorder and danger, a new republic took shape.