In the decades following the Civil War, as the frontier closed and Texas transitioned into a more settled and economically diverse state, the institutions of government took shape under the restrictive framework of the 1876 Constitution. Drafted in reaction to the centralized power wielded by Republican governors under federal oversight during Reconstruction, the Constitution created a system rooted in local control, weak executive authority, and rigid constraints on taxation and spending.

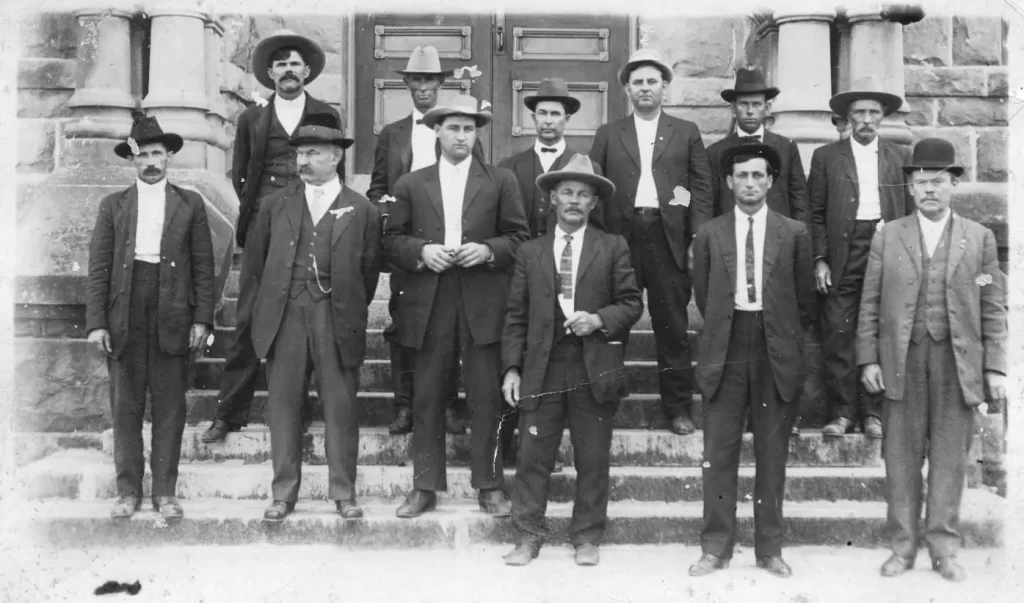

To modern Texans, many parts of this system would feel familiar in form but different in substance. County sheriffs still enforce the law, district judges still preside over trials, and voters still elect a wide range of public officials. But the institutional capacity and bureaucratic infrastructure that underpin those functions today were largely absent in the late 19th century. Government was personal, procedural norms were inconsistent, and public services were either nonexistent or handled locally.

This article examines how government operated in the post-Reconstruction period. It compares between then and now—revealing which parts of the state government were shaped by this era and which have since transformed.

Law Enforcement in Post-Reconstruction Texas

Texans in the 1880s and 1890s lived under a system of justice that was both highly local and deeply informal by today’s standards. For many citizens, the face of government was not a state agency or regulator but the county sheriff, a justice of the peace, or perhaps a traveling district judge.

Popular images of the era—revolvers, posses, dusty towns, and quick justice—are rooted in a kernel of truth. Law enforcement in Texas during this time was loosely organized, thinly spread, and often had to rely on community deputization or informal means of control. Sheriffs and marshals might raise posses to track down fugitives. The Texas Rangers, still a relatively small and decentralized force, were involved in everything from cattle theft investigations to violent suppression of political unrest, especially in South Texas.

But the reality was often less dramatic than Hollywood portrayals. Violence was common, but the vast majority of Texans lived relatively ordinary lives governed by mundane local procedures and patchy enforcement.

The state’s law enforcement apparatus was not uniform or centrally managed. There was no Department of Public Safety, no crime labs, and no formal police training academies. Officers were elected or appointed, learned on the job, and frequently relied on local knowledge and personal networks rather than standardized procedure.

The Judiciary Before Professionalization

Judicial power in post-Reconstruction Texas was similarly fragmented. The 1876 Constitution established a multi-tiered court system that still exists in some form today: justice courts, county courts, district courts, and appellate courts, all with overlapping jurisdiction. However, most legal disputes—especially criminal and civil matters below the felony level—were resolved by justices of the peace and county judges, many of whom had no formal legal training.

Even at the district court level, where felony trials and serious civil cases were heard, judges were elected and operated with significant discretion. The legal system was only lightly professionalized. Lawyers accessed statutes through printed codes when they could get them, but these were not always up to date or readily available in rural areas. Common-law principles, community norms, and precedent carried great weight. Court rules varied by district, and written opinions were not always published.

The bar examination system was rudimentary or nonexistent. Many lawyers “read law” under the supervision of a practicing attorney or judge and were admitted to practice without formal schooling. The first law schools in Texas were just beginning to emerge, but most legal professionals were self-trained or apprenticed. Judicial decisions often reflected personal judgment, political affiliations, or local custom more than consistent interpretation of codified law.

In this environment, legal practice was often improvisational. Trials might be held in county courthouses or temporary buildings, with juries drawn from the local population. There were no statewide court reporters, no digital dockets, and few standardized evidentiary procedures. Appeals to higher courts could take months or years to resolve, especially in cases involving land disputes or criminal convictions.

Elections Before Reform

The structure of elections in post-Reconstruction Texas was barely recognizable by today’s standards. Texas held general elections, but there were no party primaries, no secret ballots, and few safeguards against fraud. Most election procedures were handled at the county level, often informally and without meaningful state oversight. Local political machines and courthouse factions exerted outsized influence.

Political parties selected their nominees in conventions rather than through primaries, which meant that candidate selection was dominated by party insiders. The Australian-style secret ballot was not introduced in Texas until the 1890s, and even then, implementation was inconsistent. Before that, voters brought handwritten or pre-printed ballots—making vote buying and intimidation easier.

Without a statewide voter registration system or standardized procedures, county officials had wide discretion over election conduct, including appointing election judges and counting ballots. Fraud, ballot stuffing, and intimidation were common, especially in contested local races. Some local power struggles erupted into violence, such as the Jaybird-Woodpecker War of 1889. Participation by Black and poor white voters declined sharply after the introduction of the poll tax in 1902.

Public demand for reform led to the Terrell Election Laws of 1903 and 1905, which established state-supervised primaries, introduced regulations for party conduct, and modestly improved ballot integrity. Yet these same laws helped solidify one-party rule and laid the legal foundation for whites-only Democratic primaries that persisted for decades.

Though Texas today conducts tightly regulated elections, the legacy of decentralized control and evolving access rules can still be traced back to this formative period.

Government Without Records

Transparency in post-Reconstruction Texas government was virtually nonexistent by modern standards. There were no open meetings laws, no public information statutes, and no expectation that government officials would make decisions in view of the public or maintain accessible records.

Most governing bodies kept handwritten minutes, if they kept records at all. Public access to government documents was limited not only by custom but also by geography and technology. A citizen who wanted to review a government contract or examine a local tax roll would have to travel in person to a courthouse and request access — a request that might or might not be granted.

Legislative proceedings were not broadcast or recorded, and local officials could deliberate in private without legal consequence. Even major state agencies, such as the General Land Office, operated with limited oversight and little obligation to share information with the public. Laws governing archiving, document retention, and public access would not be adopted until the mid-20th century.

By contrast, modern Texas law mandates a high degree of government transparency. The Texas Public Information Act (originally passed in 1973) and the Texas Open Meetings Act impose disclosure requirements on virtually every public body. Meeting agendas must be posted, executive sessions are limited, and citizens have the right to inspect or request copies of public records. These expectations would have been foreign to 19th-century Texans, who were accustomed to a more opaque and discretionary model of governance.

Education and Social Services in the 1880s–1890s

State-run social services were almost entirely absent from Texas government during the post-Reconstruction period. There were no statewide systems for welfare, unemployment, public health, or child welfare. Assistance to the poor was left to county governments, churches, or private charities, and support often came with strict moral expectations or racial exclusions.

Counties sometimes maintained pauper rolls, which listed residents deemed too poor to support themselves. These individuals might receive small cash stipends, food rations, or be sent to county-run poor farms. Children without family support were often placed in orphanages run by religious organizations. Medical care for the indigent was scarce and usually offered only in large cities or by church-affiliated hospitals.

Public education in the 1880s and 1890s was constitutionally mandated but locally implemented and unevenly resourced. The Texas Constitution of 1876 required the Legislature to establish and maintain an “efficient system of public free schools,” and it created the Permanent School Fund to support public education long-term. However, state-level funding and oversight were minimal, and the actual administration of schools was left to local school districts and county school boards, which varied widely in capability and commitment.

The absence of a centralized education bureaucracy meant that curriculum, teacher qualifications, and school calendars differed sharply between regions. In rural areas, schools often operated for only a few months each year, with poorly paid and often untrained teachers.

The first stirrings of a public health bureaucracy did not emerge until the early 20th century. The State Board of Health, established in 1903, had limited authority and few resources. Disease outbreaks, particularly of yellow fever and tuberculosis, prompted some public concern, but the state’s ability to coordinate health responses was minimal.

In contrast, Texas today operates a vast network of state-administered programs, including Medicaid, foster care, SNAP benefits, and public health initiatives. While the quality and reach of these services remain a topic of political debate, their existence reflects a fundamental transformation in the relationship between Texans and their government.

Taxation and Revenue: Funding a Minimal State

The 1876 Constitution placed severe restrictions on taxation and debt, reflecting a deep mistrust of centralized financial authority. The state relied heavily on property taxes, fees, and land sales to fund its limited operations. There was no income tax, no sales tax, and little appetite for expanding revenue streams to support broader government functions.

Local governments, particularly counties, were similarly constrained. Bond issues for public works or schools required voter approval and were often capped by constitutional limits. These restrictions ensured that government remained small — but they also meant that public investment in infrastructure, education, and welfare lagged behind population growth.

Because so few services were provided at the state level, the revenue needs were relatively low. But as demands for regulation, education, and public health increased in the early 20th century, these constraints began to pose significant challenges. Texas would ultimately adopt new revenue tools, including a franchise tax, fuel taxes, and eventually a sales tax, to keep pace with its growing population and economy.

Hiring, Patronage, and Professionalism in the Civil Service

By modern standards, Texas state government in the 1880s and 1890s was astonishingly small. Most state functions were carried out by elected officials and their personal staff, while counties and municipalities bore the bulk of day-to-day responsibilities. There were no sprawling agencies, no centralized budget offices, and no civil service protections. Many offices operated with little more than a desk, a clerk, and a typewriter—if that.

The 1876 Constitution was designed to keep government lean and decentralized. The executive branch was fragmented across a plural executive, with independently elected officials controlling separate domains. This limited the governor’s influence and made coordinated policy implementation nearly impossible.

Government hiring followed a spoils system. Jobs were distributed through political connections, personal trust, and party loyalty—typically Democratic loyalty in this era. There were no competitive applications or merit-based standards. Clerks, tax assessors, jailers, and marshals were often chosen informally, and turnover was high. Many roles lacked job descriptions or training requirements. In rural counties, some officials were even paid through fees collected directly from the public rather than fixed salaries.

The idea of a nonpartisan or professionalized administrative class had not yet taken root. When new officials entered office, they frequently replaced the entire staff, erasing institutional memory. Even critical agencies like the General Land Office, which oversaw land grants and mineral rights, were modest in staffing and vulnerable to patronage.

Only in the final years of the 19th century did the state begin to modestly expand its capacity. The creation of the Railroad Commission in 1891 marked a turning point, as it required staff with technical and legal expertise—signaling the early stages of a more modern administrative state.

Conclusion: A State Built to Resist Its Own Growth

The political and institutional order created in the aftermath of Reconstruction was designed to be limited, local, and resistant to change. Texans in the late 19th century lived under a system where government jobs were handed out through patronage, public records were kept in ledgers, and essential services were left to chance or charity.

This was not an accidental outcome. The Constitution of 1876 deliberately curbed executive power, fragmented authority, and made it difficult for the state to expand its reach. Yet as the 20th century unfolded, the realities of urbanization, economic growth, and public expectation began to chip away at these limitations.

The next phase in the story of Texas governance would involve the rise of the bureaucratic state: new agencies, new regulatory powers, and a growing class of professional civil servants. That evolution was far from smooth, but it marked the beginning of modern governance in Texas—a story taken up in the decades that followed.

Related Reading

Dive deeper into this topic by purchasing any of these recommended books. As an Amazon Associate, Texapedia earns a commission from qualifying purchases. Earnings are used to support the ongoing work of maintaining and growing this encyclopedia.