In 1974, Texas came closer than ever to replacing its 100-year-old constitution. A new document had been drafted, debated, and refined. But in the end, it failed—by just one votes. This article explores how that happened, why it mattered, and what it means for today.

Background: A Constitution Out of Step with the Times

The Texas Constitution of 1876 was born of distrust—distrust of centralized government, Reconstruction-era abuses, and unchecked executive power. Its authors sought to bind future officeholders with detailed provisions that left little room for interpretation. The result was a lengthy, restrictive, and often redundant document.

By the 1970s, that constitution had become widely viewed as obsolete. It had been amended over 200 times. Critics across the political spectrum complained that it micromanaged local governments, fragmented the judiciary, and left the executive branch weak. Calls for reform grew louder as Texas modernized.

In 1971, the Legislature authorized the creation of the Texas Constitutional Revision Commission, a bipartisan group of experts, lawmakers, and public officials charged with drafting a modern constitution. Their work laid the foundation for what would become the 1974 Constitutional Convention.

The Convention: A Legislature Wearing Two Hats

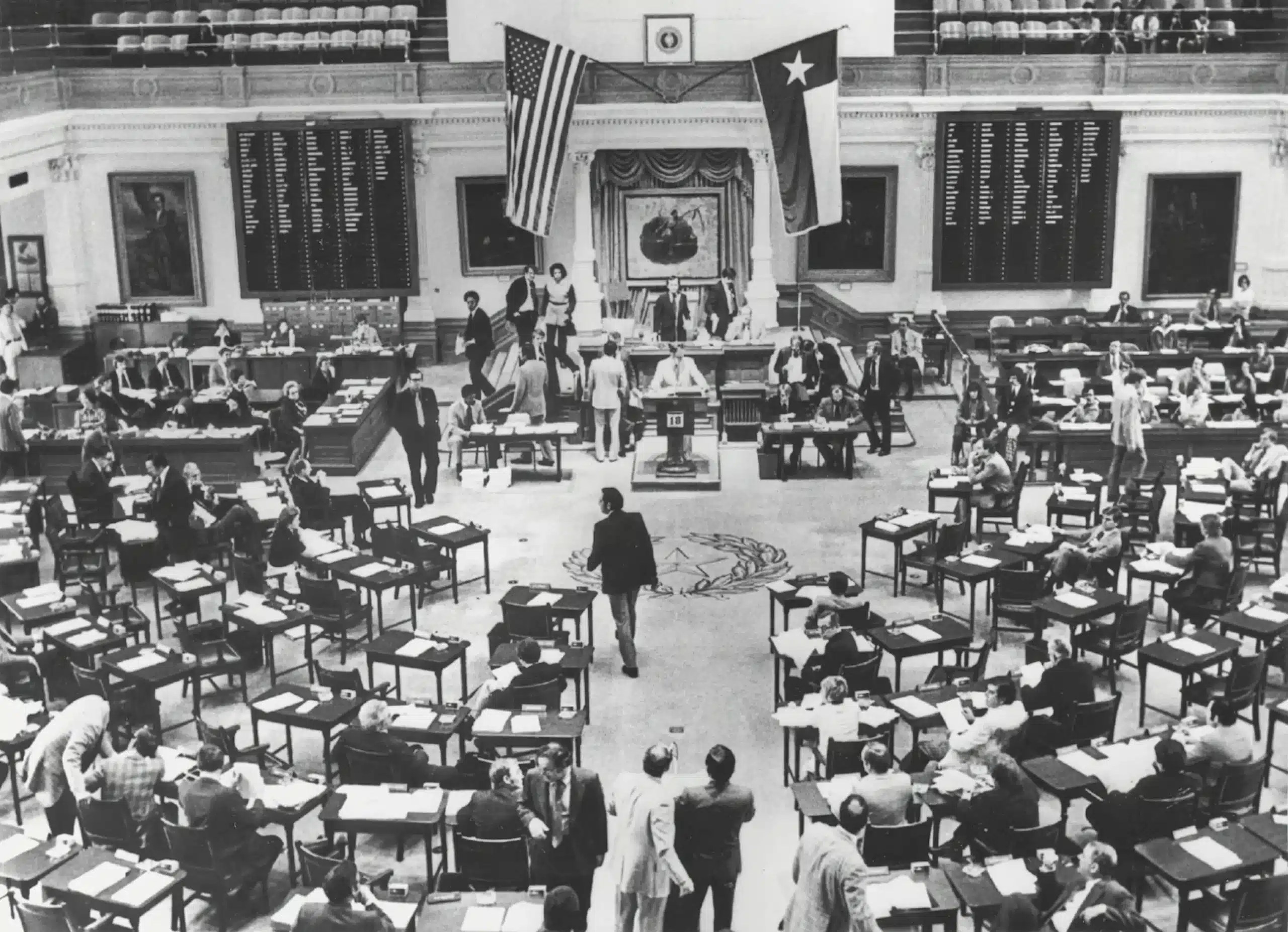

Rather than elect separate delegates, the Legislature decided to serve as its own constitutional convention—a unique and controversial arrangement. The 181 members of the House and Senate met in joint session beginning in January 1974 to deliberate over the new draft.

They broke into committees, held public hearings, and debated each article. The goal was a modern, simplified constitution that preserved essential rights while streamlining government operations. The process continued through the spring and summer, with intense negotiation and mounting political pressure.

What the New Constitution Proposed

The new draft constitution retained many core values of the 1876 document but proposed major structural changes:

- Executive Power: The governor’s role would be strengthened with unified control over appointments and budgeting.

- Local Control: Cities and counties would gain clearer home-rule authority.

- Judicial Reform: Judges would be appointed by merit and retained through voter approval.

- Open Government: New transparency rules would require open meetings and records.

- Simplification: Entire sections deemed outdated or unnecessary—such as detailed railroad regulations—were removed.

The language was clearer. The structure was more coherent. Reformers were optimistic.

Why It Failed: Division, Intrigue, and a Party in Transition

By 1974, Texas politics were in flux. The Democratic Party still dominated statewide offices and the Legislature, but that dominance masked deep ideological divisions. Conservative Democrats, especially from rural districts, often aligned more closely with Republicans than with the liberal wing of their own party. Meanwhile, the Republican Party was growing but had not yet solidified power—it was still years away from the GOP sweep of the 1990s.

The constitutional convention became a battlefield for these factions. Liberal Democrats pushed for stronger protections for labor, civil rights, and open government. Conservatives sought a right-to-work clause to prohibit union security agreements. Both sides viewed the constitution as a chance to cement long-term ideological gains.

Governor Dolph Briscoe, a conservative Democrat, remained largely aloof from the process. His neutrality—or perceived disengagement—left the convention without a unifying executive figure to push reforms across the finish line. At the same time, Lt. Governor Bill Hobby and House Speaker Billy Clayton, both Democrats, struggled to maintain order and consensus.

Behind closed doors, lobbyists worked to undermine compromise. The business lobby opposed many transparency and labor provisions. Religious conservatives feared judicial reforms might weaken moral influence over the courts. Progressive lawmakers complained of backroom deals and deliberate sabotage by right-wing Democrats who had no interest in constitutional change.

Intra-party friction proved especially destructive in the Senate, where a few conservative Democrats, under pressure from both their districts and powerful interest groups, refused to support the final draft.

On July 30, 1974, the full convention voted 118–62 in favor of submitting the new constitution to voters. But under the rules, a two-thirds vote—121 out of 181 delegates—was required. Falling just three votes short, the motion failed, and the proposed constitution died without reaching the ballot.”²

The collapse wasn’t just about the content of the document. It reflected a deeper reality: the Texas Legislature was no longer a unified Democratic body. It was a collection of competing ideologies under a fading partisan umbrella—one that would soon give way to a two-party era defined more clearly by national alignments.

Aftermath and Legacy

The fallout from the failed convention was immediate. Several lawmakers who had supported the new constitution lost re-election after being painted as liberal or anti-business. Others retreated from further reform efforts. The political cost of bold constitutional change became clear.

In 1975 and 1976, the Legislature attempted to salvage parts of the draft through standalone amendments. A few passed, including provisions for open government, judicial retirement, and improved local governance. But most failed. The moment had passed.

The convention’s failure marked a turning point. It signaled the beginning of the end for the old Texas Democratic coalition and exposed the limits of bipartisan reform in an era of deepening ideological polarization. In the decades since, no serious effort has been made to rewrite the Texas Constitution wholesale.

The 1974 convention is a cautionary tale about procedural failure, political compromise, public trust, and the difficulty of large-scale reform. It reveals the deep tensions in Texas politics—between local control and statewide uniformity, between tradition and reform.