The Constitutional Convention of 1875 marked one of the most consequential turning points in Texas political history. In the wake of the Civil War and Reconstruction, Texans assembled to dismantle the centralized Constitution of 1869, drafted under military rule, and to replace it with a new charter designed to curb governmental power. Delegates sought to craft a document that reflected a broad distrust of concentrated authority and a preference for local control.

The resulting Constitution of 1876, still in effect today, embodied a political philosophy of limited government, localism, and fiscal restraint that has shaped Texas governance for nearly 150 years.

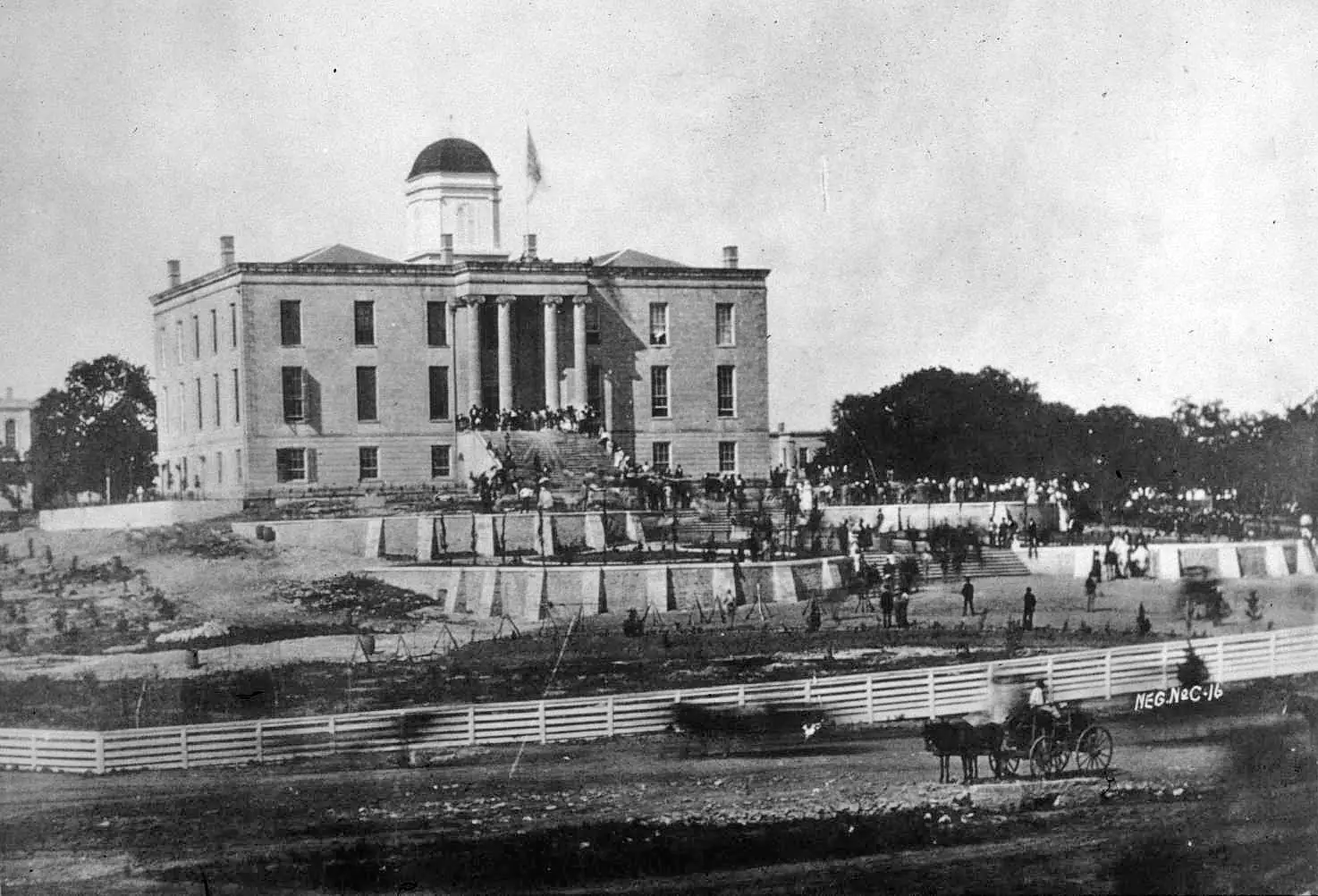

The convention gathered in Austin, meeting in the hall of the House of Representatives at the Limestone Capitol—since replaced by the present building—from September to November 1875. Presided over by Edward B. Pickett and assisted by secretary Leigh Chalmers, the delegates worked for nearly three months in committees and plenary sessions to hammer out the framework of government.

Historical Context: The Redeemer Ascent

The road to the 1875 convention began with the Constitution of 1869, drafted under Republican control during Congressional Reconstruction. That charter created a centralized and powerful state government, enlarging the governor’s authority, lengthening terms of office, and establishing a compulsory system of public education under a statewide superintendent. These provisions, defended by Republicans as necessary to modernize Texas, became rallying points for Democratic opposition.

The strongest symbol of this centralization was Governor Edmund J. Davis, the state’s Republican leader from 1870 to 1874. His administration exercised sweeping powers, including control over a newly created state police force established by an 1870 law. Democrats denounced the force as partisan and coercive, and Davis himself as emblematic of executive overreach. Controversy deepened with the Semicolon Court decision of 1873, in which the Texas Supreme Court’s reading of election law favored Republican interests, fueling charges of judicial manipulation. These tensions culminated in the disputed Coke–Davis election of 1873, resolved only after Democrat Richard Coke forced Davis from office in early 1874. For many Texans, the episode confirmed the dangers of a powerful executive and unaccountable judiciary.

With Davis’s departure, the Redeemer Democrats consolidated power and pressed for constitutional revision. Initially, however, they were divided over how to draft the new constitution, with the Senate preferring a constitutional convention and the House of Representatives preferring a commission. This delayed progress toward a new constitution throughout 1874.

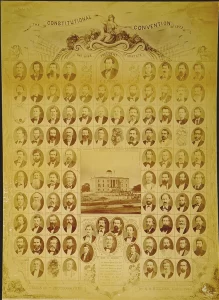

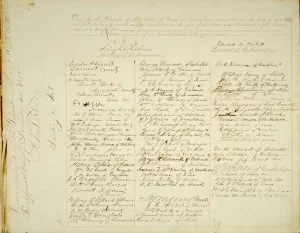

By March 1873, public pressure had swung the debate in favor of a convention, and the legislature adopted a joint resolution calling for a statewide election on August 1, 1875. Voters not only approved holding the convention but also chose delegates. Representation was based on senatorial districts, with each of the thirty districts electing three delegates, producing a body of 90 members in all.

Those delegates included a large number of former Confederates, many of them officers who had carried into peacetime the same suspicion of centralized authority that had marked their resistance to Union power. Several had served in the Secession Convention of 1861 or in the short-lived 1866 convention, bringing with them a constitutional outlook shaped before and after the Civil War. They were joined by a sizable bloc of Grange members—agrarian activists determined to restrain corporations, limit debt, and reduce public expenditures. Though varied in background, the convention was united by a determination to weaken executive authority and to restore local control, ensuring that no future governor could wield the sweeping powers associated with Edmund Davis.

A minority of about 15 Republican delegates, including six Black Texans, took part in the convention. Their presence reflected the continued political influence of freedmen and Unionist constituencies during the 1870s. Outnumbered five to one, they had little ability to alter the outcome, but they did voice opposition to dismantling the centralized public school system and raised concerns about weakening protections that had benefited their communities. While their arguments were largely overridden, their election to the convention showed that Black political participation in Texas persisted well into the late 1870s and 1880s, even as Democrats reasserted control over the state’s constitutional framework.

Many Democratic leaders were also associated with the Ku Klux Klan or sympathetic to its aims during this era, a reminder that the movement for constitutional retrenchment was entwined not only with agrarian and fiscal concerns but also with the racial politics of Redemption.

Political Philosophy of the Delegates

Of the 90 elected delegates, 41 were farmers, 29 were lawyers, 75 were Democrats, and 15 were Republicans. The guiding spirit of the 1875 convention was suspicion of government. Delegates had lived through the Civil War, federal military occupation, and the tumultuous years of Reconstruction. Their solution was to design a constitution that would prevent any concentration of power in the hands of the executive, the legislature, or even the judiciary.

- Weak Executive: The governor’s powers were curtailed sharply. Appointment authority was reduced, militia control limited, and terms of office shortened. A plural executive system was created in which key officials — such as the attorney general, comptroller, and land commissioner — would be elected independently rather than appointed, ensuring that no single official dominated state government.

- Legislative Restraint: The legislature was bound by tight limits on taxation, debt, and appropriations. The legislature would meet only biennially, not annually, unless special sessions were called. Per diem and legislators’ salaries were set low, discouraging long sessions or professional legislators.

- Agrarian Influence: With some forty delegates affiliated with the Grange, the convention reflected populist hostility to corporations, railroads, and banks. State banks were abolished outright. Railroad regulation and land policy were placed under constitutional restrictions to prevent perceived abuses by concentrated wealth.

- Judiciary: Judges were to be elected for short terms, not appointed, and jurisdictional limits curtailed judicial authority. Importantly, the 1876 Constitution divided appellate power between the Supreme Court (civil cases) and a newly created Court of Appeals (criminal jurisdiction), a change directly connected to lingering distrust of the judiciary after the Semicolon Court controversy.

- Localism: The convention strengthened local self-government by restoring control of schools, taxation, and law enforcement to counties and municipalities. Sheriffs, constables, and many other county officers were to be elected by local voters, reflecting the conviction that power should rest as close to the community as possible rather than in Austin. The first statewide road tax, introduced during the Reconstruction-era Davis administration, was repealed and replaced with county-level taxation for roads and bridges.

Underlying these provisions was a political philosophy of constitutional distrust. Unlike the U.S. Constitution, which relies on broad grants of power tempered by checks and balances, the 1876 Texas Constitution sought to enumerate powers narrowly and to forbid many functions outright. It reflected the delegates’ conviction that liberty could be secured only by making government weak, cheap, and decentralized.

“This was an antigovernment instrument; too many Texans had seen what government could do, not for them but to them. It tore up previous frameworks, and its essential aim was to try to bind all state government within very tight confines… The dominant spirit was to allow the state government no real latitude to act.”

Historian T.R. Fehrenbach

Federal vs. Texas Constitutions

The contrast with the federal model is stark:

- Length and Detail: The U.S. Constitution is concise and general. The Texas Constitution of 1876 is sprawling and prescriptive, regulating everything from debt limits to railroad charters.

- Executive Power: The federal president embodies a unitary executive. Texas adopted a plural executive, fragmenting authority across multiple elected officials.

- Implied Powers: The federal system includes the “necessary and proper” clause, allowing flexibility. Texas placed explicit restrictions on taxation, borrowing, and legislative scope, leaving little room for implied powers.

- Judiciary: Federal judges hold life tenure. In Texas, judges are elected for short terms and subject to frequent turnover, reflecting mistrust of an insulated judiciary.

- Amendment: The federal Constitution is amended rarely. Texas designed a process that has been used hundreds of times, embedding constitutional detail in areas where other jurisdictions would rely on ordinary legislation.

These contrasts highlight the intellectual divergence between national constitutionalism, which emphasizes energetic government balanced by checks, and Texan constitutionalism after 1875, which emphasized restraint through diffusion of authority.

Differences from Predecessor Constitutions

While the Constitution of 1876 was born out of a determination to roll back Reconstruction centralization, it also carried forward long-standing features of Texas constitutionalism. The Constitution of the Republic of Texas (1836) had established the county form of local government, a system that endured and was further entrenched in 1876. Offices such as sheriffs, constables, and county commissioners, first provided for under the Republic and retained in 1845, were continued and given even stronger constitutional grounding.

The Constitution of 1845, drafted at statehood, established many of the principles Texans would preserve for generations: short terms of office, relatively low salaries, and a tendency to elect rather than appoint public officials. Its structure reflected a cautious balance, with a governor stronger than under the Republic but still constrained, and a judiciary designed to be independent yet subject to popular control.

The 1869 Constitution, by contrast, reflected the centralizing priorities of Reconstruction: it lengthened terms of office, concentrated power in the governor, and created the constitutional office of Superintendent of Public Instruction to administer a uniform and compulsory system of schools. The 1876 Constitution repudiated those features by curbing executive authority, shortening terms, lowering salaries, and removing the superintendent’s office, thereby returning control of education and other key functions to local hands. A superintendent was later re-established by statute in the 1880s, but without the sweeping constitutional powers of 1869. In this way, the new charter both reversed Reconstruction centralization and reaffirmed older Texan traditions of county government and elected local officials.

Ratification Election of 1876

On November 24, 1875, after nearly three months of work, the convention approved the draft by a vote of fifty-three to eleven. The new constitution was submitted to the electorate on February 15, 1876, and ratified. The campaign centered on promises of fiscal economy and restoration of local self-government. With Democrats firmly ascendant, opposition was muted, and the document entered into effect.

Legacy and Subsequent Amendments

The Constitution of 1876 inaugurated a long era of Democratic dominance in Texas. For nearly a century thereafter, the Democratic Party controlled every statewide office and the legislature, operating within the framework established by the convention. Its distrust of executive power and preference for localism became hallmarks of Texas political culture.

Over time, however, the document’s rigidity became a liability. Because it confined the legislature with detailed restrictions, any new program often required a constitutional amendment. As a result, Texas has accumulated hundreds of amendments, covering subjects as varied as teacher retirement funds, road bonds, and water projects. The constitution is among the longest in the world.

In the 1970s, reformers sought wholesale replacement. A 1974 convention produced a proposed modern constitution, streamlined and reorganized, but the effort failed by a single vote in the legislature. The result left Texas with its 19th-century framework, patched by amendments but fundamentally unchanged.

Despite repeated efforts at modernization, the core structure of the 1876 charter remains intact: a plural executive, weak governor, elected judiciary, and reliance on local control.

Criticisms and Revisionism

Commentators over the decades have faulted the 1876 Constitution for being overly detailed, cumbersome, and outdated. Its drafters’ suspicion of centralized power may have suited the 19th century, but in a modern, urban, and populous state, the diffusion of authority can make coherent policymaking difficult. Calls for revision have come from reformers in the Progressive Era, the mid-20th century, the 1970s, and the present day, each pointing to various inefficiencies or flaws.

Michael Ariens, for example, author of a legal history of Texas, pointed out that the 1876 constitution went against the traditional American view of a constitution by legislating minor matters rather than focusing on the broad structure of government. Historically, drafters of American constitutions, both state and federal, have expected these documents to outline the broad structure and principles of government—not to legislate in detail. But the 1876 constitution of Texas, consisting of over 63,000 words, “embraced the ‘prolixity of a legal code.'”1

Some historians have criticized the 1876 constitution as resting on an exclusionary vision of democracy. While delegates drew on populist and agrarian distrust of railroads, corporations, and banks, their insistence on local control was equally shaped by the racial politics of Redemption. The same provisions that curbed central authority and curtailed corporate privilege also dismantled statewide structures that had protected freedmen’s rights. In practice, the constitution’s “democratic” provisions narrowed the electorate and empowered local authorities who often acted in concert with groups like the Ku Klux Klan to suppress Black political participation.

In terms of historical legacy, the Constitutional Convention of 1875 cannot be separated entirely from the era of racial repression, mass incarceration, and one-party rule that followed. Yet the political philosophy embodied in the 1876 Constitution — a philosophy of limited government, a weak executive, and fiscal restraint — has endured long beyond the dismantling of the Jim Crow system, and remains a celebrated part of Texan political culture.

- Michael Ariens, Lone Star Law: A Legal History of Texas (Lubbock: Texas Tech University Press, 2011), pg. 47. The phrase ‘prolixity of a legal code’ is a quotation of U.S. Chief Justice John Marshall in the opinion in McCulloch v. Maryland (1819). The justice wrote, “A constitution, to contain an accurate detail of all the subdivisions of which its great powers will admit, and of all the means by which they may be carried into execution, would partake of the prolixity of a legal code, and could scarcely be embraced by the human mind.” ↩︎