In 1861, as Texas seceded from the Union and joined the Confederate States of America, it adopted a new state constitution that reflected the political ideologies and priorities of the secessionist movement in the South. While many structural elements of the earlier 1845 Constitution were retained, the 1861 version went further in explicitly entrenching slavery, aligning state governance with Confederate principles, and embedding White Supremacy into the legal order.

It was a wartime document, adopted in a militarized environment in which dissent was barely possible and loyalty to the rebellion was demanded. This article explores the origins, content, and legacy of the Confederate Constitution of Texas, with particular focus on Article VIII and its codification of racial violence and property rights in human beings.

Secession Convention

The Texas Secession Convention convened in Austin on January 28, 1861, following the election of delegates on January 8 in a process that often excluded Unionist voices. Meeting in the old state capitol, the convention was dominated by slaveholders and pro-secession Democrats. On February 1, the delegates voted overwhelmingly to secede from the Union.

This decision was ratified by popular vote in a statewide referendum held on February 23.

The convention reconvened on March 5 to adopt a new state constitution, aligning Texas with the Confederate States of America. The resulting document preserved much of the 1845 Constitution’s structure but removed all references to the United States and pledged loyalty to the Confederacy.

Defense of Slavery

The most striking changes in the 1861 Constitution appear in Article VIII, a dedicated section titled “Slaves.” This article codified slavery not just as a social fact but as a legal mandate, depriving both the legislature and private individuals of the ability to emancipate enslaved people. Section 1 bluntly declared, “The Legislature shall have no power to pass laws for the emancipation of slaves.”

Section 2 extended that prohibition to private actions: “No citizen, or other person residing in this State, shall have power… to emancipate his slave or slaves.” This made slavery functionally permanent and intergenerational.

The article also welcomed the expansion of slavery through immigration. Section 3 stated that slaveholders from other Confederate states could bring enslaved people with them into Texas, with the sole exception of slaves convicted of felonies.

Sections 4 through 6 superficially extended certain legal protections to enslaved people. Section 4 guaranteed a trial by jury for enslaved defendants in serious criminal cases, but this right could be suspended in cases of slave insurrection.

Section 5 prohibited malicious killing or mutilation of slaves, prescribing the same punishment as for similar offenses against White persons—except in cases where the slave was accused of insurrection or of attempting to rape a White woman. This exception relied on the racial trope of the Black male rapist, a stereotype used to justify extrajudicial killings and vigilante violence. It granted legal cover for retribution killings and lynchings while maintaining the illusion of legal restraint.

Section 6 empowered the Legislature to require slaveowners to treat slaves with ‘humanity,’ but the term was left undefined, and no enforcement mechanism was provided. The clause functioned more as rhetorical cover than legal safeguard, giving the appearance of moral concern without curbing abuse.

Together, these provisions used the language of law and order to institutionalize racial domination. Even the gestures toward due process and humane treatment were compromised by exceptions that legitimized violence and denied actual legal personhood to the enslaved. The racialized exception in Section 5 was particularly revealing: while it acknowledged that killing a slave might be murder, it simultaneously sanctioned execution without consequence if the victim was accused of sexual violence against a White woman. This codified the lynching-era rape myth and invited violence under the guise of moral protection.

Changes from the 1845 Constitution

I, _______ do solemnly swear (or affirm) that I will faithfully and impartially discharge and perform all the duties incumbent on me as _______, according to the best of my skill and ability, agreeably to the Constitution and laws of the State of Texas, and also to the Constitution and laws of the Confederate States of America, so long as the State of Texas shall remain a member of that Confederacy.

And I do further solemnly swear (or affirm) that since the second day of March, A. D., 1861, I, being a citizen of this State, have not fought a duel with deadly weapons, within this State nor out of it; nor have I sent or accepted a challenge to fight a duel with deadly weapons; nor have I acted as second in carrying a challenge; or aided, advised or assisted any person thus offending—so help me God.”

Loyalty oath required by the 1861 Texas Constitution, Article VII §1

While the protection of slavery was the most visible transformation, other changes in the 1861 Constitution reflected Texas’s new political orientation. Many governmental structures remained intact, including the bicameral legislature, elected executive branch, and district court system. However, the new constitution included several provisions aligning Texas law more explicitly with Confederate ideology:

- All references to the United States were removed and replaced with affirmations of allegiance to the Confederate States of America.

- A new loyalty oath required officeholders to swear allegiance to the Confederacy.

- The legislature was limited in its ability to fund internal improvements, reflecting Southern skepticism toward centralized economic development.

- Tariff powers were restricted in deference to Confederate free trade ideals.

- A clause mandated that any new state debt had to be covered by direct taxation.

These changes reflected both ideological alignment and fiscal conservatism, as Texas joined a Confederacy deeply suspicious of federal-style power and committed to preserving a slave-based agrarian economy.

Unionist Opposition Within Texas

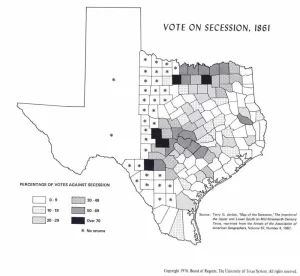

Though the 1861 Constitution was adopted by popular vote, opposition to secession and Confederate governance was widespread in parts of Texas. Governor Sam Houston famously refused to swear loyalty to the Confederacy and was removed from office. In Central Texas, German immigrant communities and religious minorities such as Methodists and Quakers objected to slavery and military conscription. Some counties in the Hill Country remained Unionist strongholds throughout the war.

These tensions revealed that the Confederate Constitution did not represent all Texans—particularly not the enslaved or those morally opposed to secession—but rather codified the will of a politically dominant planter class.

Comparison to Other Confederate States

Texas’s 1861 Constitution was among the more aggressive Confederate state constitutions in banning emancipation both legislatively and privately. Some Confederate states, such as Georgia or North Carolina, preserved limited pathways for manumission. Texas’s explicit protections for slave importation and its racialized legal exceptions placed it closer to the hardline model used by Mississippi and South Carolina.

Compared to other Confederate states, Texas took a distinctive approach in several non-slavery provisions. While all seceding states adopted constitutions that emphasized states’ rights, Texas retained a relatively short gubernatorial term—two years—whereas states like Georgia extended executive terms to four years. Texas’s amendment process remained legislative and voter-based, while Georgia shifted authority exclusively to constitutional conventions.

On infrastructure, Texas permitted state-funded internal improvements under certain conditions, in contrast to stricter fiscal limits imposed in Georgia and Alabama. In matters of suffrage, Texas refrained from adding property requirements for White male voters, diverging from more restrictive practices in states like South Carolina. These differences reveal a constitution shaped not only by Confederate ideology but also by regional preferences.

Aftermath and Legacy

The Confederate Constitution remained in force until the end of the Civil War, when Union forces reoccupied Texas and federal Reconstruction policies were implemented. In the immediate aftermath, Texas adopted new constitutions in 1866 and again in 1869—each marking attempts to reconcile with federal authority and reestablish civil government. The 1866 Constitution made modest changes under Presidential Reconstruction but retained many elements favorable to the old order. The 1869 Constitution, imposed under Congressional Reconstruction, included more substantial reforms, such as guarantees of equal protection and the centralization of state authority.

Former Confederates gradually regained political power in the 1870s, and by 1876 Texas had adopted yet another new constitution. Although the explicit protections for slavery were gone, the social and legal assumptions embedded in the 1861 document lived on through Jim Crow laws, Black Codes, disenfranchisement tactics, and racially biased policing. The legacy of the Confederacy persisted long after its military defeat.

Related Books

Dive deeper into this topic by purchasing any of these recommended books. As an Amazon Associate, Texapedia earns a commission from qualifying purchases. Earnings are used to support the ongoing work of maintaining and growing this encyclopedia.

- Shifting Grounds: Nationalism and the American South, 1848-1865

- Colossal Ambitions: Confederate Planning for a Post–Civil War World

- The Texas Lowcountry: Slavery and Freedom on the Gulf Coast, 1822–1895

- A South Divided: Portraits of Dissent in the Confederacy

- This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War