Historical Context & Significance

In 1836, Texas fought a war to become independent from Mexico. After several months of fighting, the Texas army won a surprise victory at the Battle of San Jacinto. Mexican General Santa Anna was captured and agreed to sign documents known as the Treaties of Velasco, which called for Mexican troops to withdraw and promised that Santa Anna would support Texas independence.

However, these treaties were not accepted by the Mexican government. Mexico claimed that Santa Anna had signed them as a prisoner and had no legal authority to negotiate peace. As a result, Mexico continued to view Texas as part of its territory. The Republic of Texas, meanwhile, saw itself as an independent nation—but remained diplomatically isolated and vulnerable to renewed conflict.

By February 1837, it was clear to the Texan leadership that the Treaty of Velasco was not a sufficient or enforceable peace settlement. With no recognition from Mexico and uncertain support from the United States, Texas sought other ways to secure its independence. Diplomatic negotiation became a necessary next step.

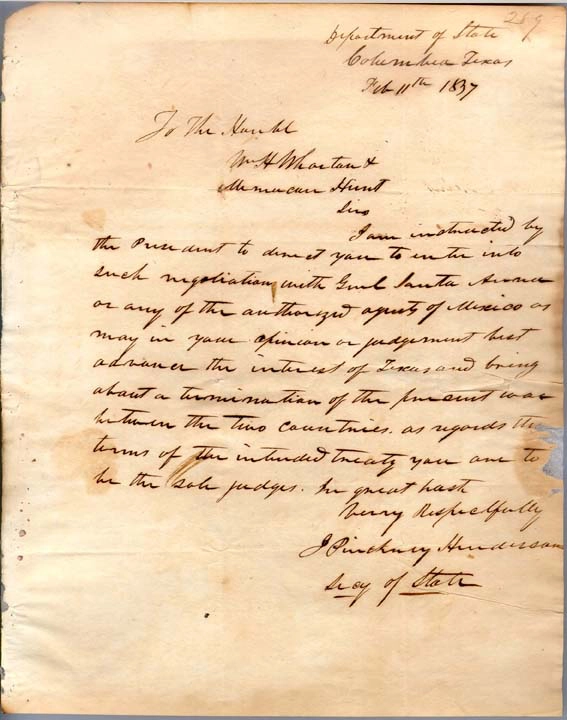

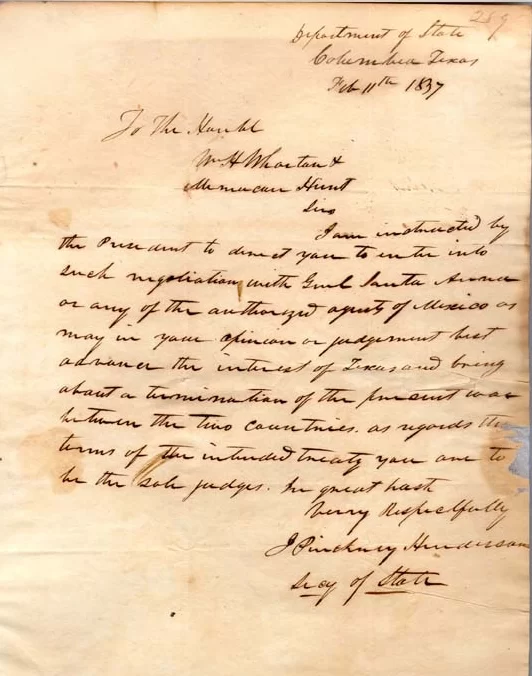

That month, Texas Secretary of State J. Pinckney Henderson wrote this letter to two appointed envoys—William H. Wharton and Memucan Hunt—who were serving as part of the Texas legation, the young republic’s official diplomatic mission abroad. Writing from Columbia, then the capital of Texas, Henderson instructed the men to negotiate peace on whatever terms they judged best—either with Santa Anna or with any other Mexican representatives willing to talk.

Meanwhile, outgoing U.S. President Andrew Jackson was pursuing his own quiet diplomacy. Though personally sympathetic to Texas, Jackson was cautious about provoking war with Mexico. Rather than granting Texas immediate recognition, he explored the idea of brokering a peace agreement that Mexico might accept.

“You are to be the sole judges,” Henderson wrote, giving the diplomats broad discretion to end the war.

Santa Anna—now in Washington, D.C. under U.S. protection—met with Jackson and American officials in early 1837. Jackson’s correspondence with Santa Anna suggests the United States was open to acting as a mediator or guarantor of Texas independence, as long as it could avoid a direct military confrontation with Mexico.

This February 1837 letter from J. Pinckney Henderson reflects a key moment in early Texas diplomacy. It captures both the urgency and uncertainty of the moment, as Texas leaders sought to secure their revolution not just on the battlefield, but at the negotiating table.

This letter is also noteworthy as a part of a larger collection of records of the Texas Legation, the diplomatic arm of the Texas government. The Legation was given the difficult task of convincing other nations to recognize the independence and sovereignty of a territory that was still, in many respects, just a frontier outpost.

Unfortunately, there is no conclusive record of Santa Anna’s contacts with Wharton and Hunt in Washington. Santa Anna returned to Mexico in late February 1837. When he returned to power, he continued to contest Texas’s independence and authorized several armed raids into Texas. Interestingly, however, Santa Anna never again launched a full-scale invasion comparable to the campaign of 1836. This restraint may reflect the success of the diplomatic outreach of 1837, combined with the deterrent of Texan arms, and the unpredictable risks of U.S. involvement.

Original Document

Transcript of the Letter

Department of State

Columbia, Texas

Feb 11th, 1837

To The Honorable

Messrs. Wharton &

Memucan Hunt

Sirs,

I am instructed by the President to direct you to enter into such negotiation with General Santa Anna or any of the authorized agents of Mexico as may in your opinion or judgment best advance the interest of Texas and bring about a termination of the present war between the two countries; as regards the terms of the intended treaty you are to be the sole judges. In great haste,

Very Respectfully,

J. Pinckney Henderson

Secy of State

Manuscript Information

The original manuscript of this letter is preserved at the Texas State Library and Archives Commission (TSLAC) in Austin, as part of the Republic of Texas’s federal diplomatic records. The digitized facsimile included in the article was made available online through the Texas Legation Papers project hosted by Texas Christian University (TCU).

The Texas Legation Papers comprise correspondence and reports from 1836 to 1845, documenting the Republic’s efforts to secure peace, recognition, and legitimacy. In 1845, when the Legation closed, its records were transferred to the U.S. Adjutant General’s Office.

Senator Sam Houston was tasked with returning the documents to Texas, but he inadvertently kept one box—containing over 250 records—at his home. These papers remained within his family for over 160 years, surviving threats like Hurricane Carla (1961), which damaged the Houston residence. They were eventually acquired at a 2006 Texas Historical Association auction by Texas Christian University, conserved, and exhibited in Fort Worth before being deposited permanently at TSLAC.