The alliance between the Republic of Texas and the rebellious province of Yucatán was one of the boldest ventures of the short-lived Texian Navy. Beginning in late 1841, Commodore Edwin Ward Moore led Texian warships to the Yucatán coast under a contract to defend the federalist peninsula against centralist Mexico. Financed by Yucatán and justified by President Mirabeau B. Lamar as a shared struggle for liberty, the campaign culminated in the Battle of Campeche (1843) — the only time in history sailing ships defeated steam-powered warships in open battle.

Yet what began as a triumph of naval diplomacy ended in bitter controversy, as President Sam Houston denounced Moore as a pirate and sought to dismantle the fleet.

The Yucatán Revolt and Mexico’s Federalist Wars

The Yucatán revolt that opened the door to alliance with Texas was part of a wider crisis within Mexico. In the late 1830s and early 1840s, the republic was repeatedly torn by conflict between centralists, who favored a strong national government dominated by Mexico City, and federalists, who sought to preserve state autonomy under the federal Constitution of 1824.

Santa Anna’s rise to power as a centralist authoritarian in 1834–35 provoked uprisings across the country, including the Texas Revolution, the short-lived Republic of the Río Grande (1839–40), and the Yucatán independence movement of 1838–1840. In each case, regional elites resented central control over local revenues, customs duties, and political appointments, and often feared the concentration of military power in the capital.

Yucatán’s revolt had both regional and racial dimensions. The peninsula’s economy was dominated by criollo landowners of Spanish descent, who relied on Maya labor for agriculture and trade but were wary of central government interference. In 1840, the Yucatecan assembly declared independence and drafted a constitution modeled on Mexico’s earlier federalist charter of 1824. The criollo elite portrayed themselves as defenders of local liberty against Mexico’s centralist army.

Yet beneath this rhetoric lay a deeper tension: the majority Maya population had little role in political life, and their grievances over land and forced labor would erupt in the devastating Caste War of 1847. In the 1840s, however, Yucatán’s criollo leaders sought recognition as a sister republic alongside Texas, presenting themselves as liberal allies in a common struggle against Santa Anna’s centralism.

Lamar’s Vision and the Yucatán Alliance

President Lamar spelled out his policy in his annual address to Congress on November 3, 1841, just weeks before Houston’s return to power. He portrayed the Yucatán rebels as natural allies of Texas. For Lamar, this was not merely opportunistic but ideological. He contrasted liberal Yucatán with the clerical and centralist politics of Mexico City:

“The present condition of Yucatán, which is now engaged, with almost a certainty of success, in a revolutionary struggle against our oppressors, has made known to this government its disposition to court friendly alliance with Texas, and to recognize her independence as soon as it is effected. This intelligent, wealthy, and populous state… instead of uniting with the benighted, corrupt, and priest-ridden portions of Mexico for our destruction, they are themselves at war with the very power that would subjugate us. It would therefore seem advisable to draw a line of distinction between them and Central Mexico, and regarding them rather in the character of allies than enemies, extend to them all the facilities compatible with discretion, so long as they continue to war with a common enemy.”

Lamar also emphasized the practical terms of the agreement. Yucatán would finance Texas naval operations. Idle ships at Galveston, Lamar argued, were both costly and deteriorating. Sending them to sea under Yucatán’s subsidy would preserve them:

“Our vessels have heretofore been kept in the harbor at Galveston, in a useless condition, at an expense too burthensome for the country to sustain in the present prostrate condition of its finances. This expense will not only be entirely saved by keeping the squadron employed under the arrangements with Yucatán, but the vessels, while in actual service, will be better preserved than they could be by any care and attention in ordinary.”

Finally, Lamar drew a clear contrast between his naval strategy and the idea of invading Mexico on land:

“Whilst we are thus annoying our enemy by water, the question naturally arises, what shall be our course toward them upon land? I have already expressed my aversion to a military invasion of their territory. … We have not the means to raise, equip, and continue in the field an army of sufficient force to chastise that nation into an acknowledgement of our independence, without involving ourselves in pecuniary difficulties and embarrassments infinitely greater than those which now surround us.”

In short, Lamar envisioned an alliance of republican states, a cost-effective way to keep the navy active, and a strategy to pressure Mexico without exhausting Texas’s treasury. On September 18, 1841, Colonel Martín Pereza of Yucatán and Texian officials formalized the deal. Three ships would defend Yucatán’s coast in exchange for $8,000 a month, with prize money to be shared.

First Sortie, 1841–1842

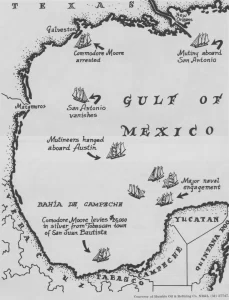

On December 13, 1841, Commodore Edwin Ward Moore sailed from Galveston with the Austin, San Bernard, and San Antonio. That same day, Sam Houston was sworn in as president. Within forty-eight hours Houston had issued orders recalling the fleet.

Moore, unaware of the recall, carried out a five-month cruise off Mexico. Moore was a 14-year veteran of the United States Navy, having gone to sea while still a boy. A skilled seaman, daring fighter, and strong leader, he took charge of the Texas Navy at the age of 29 and was in his early 30s when he led the fleet south toward Yucatán.

Operating mostly along the Yucatan Peninsula and off the coast of Veracruz, a key port city, Moore harassed Mexican commercial shipping and occasionally clashed with Mexican warships. On February 6, 1842, the Texan squadron captured the merchant ship Progreso. In April they added the Doric, the Dolorita, and the Dos Amigos. These prizes helped finance operations, but they did little to repair the rift between the Navy and Houston’s administration.

Political and Financial Strains

While Moore was in Yucatán, he sent the San Antonio back to Texas with a full report on the situation for President Houston. He included a plea for the steamship Zavala to be repaired and sent south to shore up Texan control of the coast. The steamer was never sent. Texas had only a very small navy yard, and no one who knew how to work with the temperamental steam technology. Yucatán offered to pay for the repairs, but Houston refused. Instead, the Zavala was allowed to rot so badly that it was later deliberately run aground and wrecked in Galveston Bay rather than pay the cost of repairs. Houston would not even agree to sell the engines from the wrecked ship to raise money for the rest of the fleet.

Houston believed that the aggressive military policies of his predecessor, Mirabeau Lamar, had bankrupted the young republic and needlessly antagonized Mexico. His priority was keeping tensions low with Mexico while negotiating annexation of Texas into the United States. More fighting with Mexico would complicate the annexation debate in the U.S. Congress and worsen the already bad fiscal situation. In this context, “annoying our enemy by water” was the opposite of what he felt Texas should be doing strategically.

Moreover, Yucatán had initiated truce negotiations with Mexico, and suspended its monthly $8,000 naval subsidy to Texas during a such pause in the hostilities.

Moore returned to Texas in April 1842 for provisioning, repairs, and replenishment of his crews, whose enlistment terms were running out. Though Moore intended only a short stay, Houston ordered the Austin, San Antonio, and San Bernard to New Orleans and Galveston for extensive overhaul—without providing funds for the repairs.

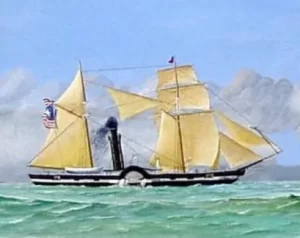

Thus began a period of intense personal conflict between Houston and Moore. Moore, however, was undeterred; he sent the San Antonio to Yucatán to ask for renewal of the monthly subsidy to finance the expedition. This ship, however, vanished in the Gulf, likely in a storm in September 1842. In the meantime, Mexico was building up its own navy, purchasing two new schooners from a New York shipyard and two steamships with Paixhans pivot guns—a new type of naval artillery that fired exploding shells long distances. Purchased from England and manned by former Royal Navy officers and mixed crews, including some English, these warships posed a formidable threat to Texan operations in the Gulf.

Despite these challenges, Moore persistently advocated for a renewal of the Yucatán expedition, and he won the backing of many Texans both in and out of government. The Mexican Army made two serious incursions into Texas in March and September 1842, occupying San Antonio each time, though not venturing farther north and east. These short-lived invasions, known as the Vásquez and Woll raids, emboldened the war party within Texas politics and undermined the position of the peace party, led by Houston.

Though Houston withheld Congressional appropriations for the Texas Navy, Moore raised funds from the Yucatán government directly, and from New Orleans and Texas merchants, who likely were promised a share in the spoils if he could again capture Mexican prizes.

Meanwhile, tensions mounted between Moore, Houston, and respective factions in the Texas Congress, as the peace party planned to halt operations in the Gulf and sell the Texas Navy to defray expenses and repay debt. The war party, on the other hand, planned to resume raids on Mexican shipping and return to the aid of Yucatán, which had come under renewed pressure from the Mexican Army and Navy, the earlier peace talks having failed.

As Moore used private means to refit his ships during the winter of 1842-1843, Houston’s secretary of war repeatedly summoned him to return to Galveston from New Orleans. In January 1843, Houston dispatched commissioners to New Orleans to bring the navy under political control and ensure that Moore did not put to sea again.

Houston asks Congress to Disband the Navy

President Houston explained his thinking on the Texas Navy in a secret message to the Texas Congress on December 22, 1842. He mentioned that the governments of Great Britain and the United States had complained of the continuance of a proclamation of blockade of Mexican ports. This influenced him to rescind the proclamation and recall Moore.

Houston also exaggerated the disrepair of the navy and the expense of maintaining it, and he questioned the seaworthiness of the crews. He wrote, “It is for the Honorable Congress to determine the question, whether Texas is in a situation to accomplish the object of keeping our Navy longer afloat, or whether a good policy does not require us to abandon that arm of defense and make sale or such other disposition of the vessels as will relieve the nation from a burden which it is so utterly unable to sustain.”

Further, Houston expressed a belief that the Texas Navy was militarily useless:

“When we advert to the history of our Navy from its first establishment to the present moment, we cannot perceive a single instance wherein any important benefit has been conferred upon the country from its action. No advantage has been achieved. This remark has not been made from any disposition to reflect any disparagement upon the officers composing the naval corps, but is founded upon facts which are to be deplored, because they have encumbered us with debt, without producing any beneficial return. Had the one twentieth part of what has been expended for the purchase and support of the navy been employed in constructing fortifications for the defence of our harbors, the debt of Texas would have been at this day millions less, and our coasts and harbors in a much more favorable attitude of defence. A clamor induced the creation of the navy. Experience has taught us the impolicy of the measure…”

“To give efficiency to our government it is proper that we should not permit any diversion of its energies. To economize our means and concentrate all our resources upon objects of unquestionable importance and utility should be our first purpose… in our present destitute condition, it is so manifest that we have not means to maintain the establishment [of a Navy] that I do not hesitate in pronouncing a further experiment as deeply injurious to the public interests.”

After delivering this message to the Congress, Houston secured Congressional approval, by means of a “secret act,” to explore the sale of the navy’s ships.

Naval Commissioners Fail to Deter Moore

Houston’s commissioners arrived in New Orleans in February 1843, just as Moore was making final preparations to put to sea. Moore had secured an agreement from Yucatán to resume monthly payments of $8,000 for the upkeep of his fleet. His depleted crews, which formerly had gone without pay, were now back up to strength.

Trading on the success of his previous expedition, Moore promised prize money to sailors who joined up, if Mexican ships could be taken. Having lost the San Antonio, Moore now had only two warships, the Austin and Wharton; yet these ships, far from being dilapidated, were in “apple pie order,” and the crews were “bully” and spoiling for a fight, Commissioner William Bryan reported.

Meanwhile, rumors circulated among the Texans in New Orleans that the Mexican warships were poorly manned by a mix of insubordinate sailors, army conscripts, and English mercenary sailors with little motivation. The Texans, with their typical bravado, believed that they could beat the Mexican Navy in a fight, notwithstanding the acquisition of new warships, including an ironclad steamer and new naval artillery.

Moore refused Houston’s orders to abandon his mission to Yucatán. He argued to Commissioners Bryan and Moore that he had promised to render assistance to the breakaway republic, which was then under siege and blockaded by Mexican warships. Moreover, he had incurred personal debts preparing for the sortie, and he could not easily abandon it. He claimed to be acting on earlier orders. Commissioner Bryan decided to returned to Texas for further instructions, and Commissioner James Morgan actually came around to Moore’s point of view and agreed to accompany him on the expedition.

Houston Declares Moore a Pirate

Houston’s envoys had failed to bring Moore under control. As word reached the Texan president in March that Moore’s departure for Yucatán was imminent, he decided to issue a final ultimatum. He wrote a proclamation on March 23, 1843, calling Moore insubordinate and relieving him of command.

Further, Houston called on friendly nations to seize Moore and his ships if they put to sea again, and to return them to Galveston. He implied quite overtly that Moore should be put on trial for piracy. The proclamation read in part:

“Post Captain E. W. Moore, has disobeyed, and continues to disobey, all orders of this Government, and… avows his intention to proceed to sea under the flag of Texas, and in direct violation of said orders… the President of the Republic is determined to enforce the laws and exonerate the nation from the imputation and sanction of such infamous conduct; and with a view to exercise the obligations of friendship and good neighborhood towards those nations whose recognition has been obtained, and for the purpose of securing the respect and harmony of commerce and the maintenance of those international rules of subordination to which all nations have been so flagrantly violated by the stubborn insubordination of any organized government, known to the present day, it has become necessary and proper to make public these various acts of disobedience, contumacy and mutiny, on the part of the said Post Captain, E. W. Moore; Therefore:

“I, Sam. Houston, President and Commander-in-Chief of the Army and Navy of the Republic of Texas… do further declare and proclaim, on failure of obedience to this command, or on his having gone to sea in defiance of the orders of this government, he no longer holds himself responsible for his acts, for he is henceforth out, but, in such case, require all the governments in treaty, amity, and friendship with this government, and all naval officers on duty in foreign seas, foreign to this country, to seize the said Post Captain, E. W. Moore, the ship Austin and brig Wharton, with their crews, and bring them… into the Port of Galveston, that the vessels may be secured to the Republic, and the culprit or culprits arraigned and punished by the sentence of a legal tribunal.

“The Naval Powers of Christendom will not permit such a flagrant and unexampled outrage, by a commander of public vessels of war, upon the rights of his nation and upon his official oath and duty, to pass unrebuked; for such would be to destroy all civil rule and establish a precedent which would jeopardize the commerce of the nations and render encouragement and sanction to piracy.”

Though dated March 23, this proclamation was not published in Texan newspapers until May, after Houston learned that Moore had sailed for Yucatán. However, in April the proclamation likely was conveyed to Moore privately, as a warning, since he preemptively wrote a public reply, addressed to the editor of the Texas Times in Galveston:

“In the event of my being declared by Proclamation of the President as a Pirate, or outlaw; you will please state over my signature that I go down to attack the Mexican Squadron, with the consent and full concurrence of Col. James Morgan, who is on board this Ship as one of the Commissioners to carry into effect the secret act of Congress, in relation to the Navy, and who is going with me, believing as he does that it is the best thing that could be done for the country. This Ship and the brig have excellent men on board, and the officers and men are all eager for the contest.—We go to make one desperate struggle to turn the tide of ill luck that has so long been running against Texas.”

This letter was dated April 19 and was written while Moore was anchored at the mouth of the Mississippi, on the day of his departure for Yucatán. However, it was not published until April, after Houston circulated his own proclamation.

The sympathetic editor of the influential Telegraph and Register, Francis Moore, republished this letter under the heading “COM. MOORE NO PIRATE,” commenting, “The following certificate shows that Commodore Moore, instead of disobeying orders, is actually now acting with the full consent and concurrence of President Houston’s own Commissioner, Col. James Morgan. This shows the propriety of requiring Presidents and others in authority, to wait until a man is proved to be guilty before he is condemned. Tyrants, however, observe no such maxim… The fact that Col. Morgan our Commissioner has sanctioned the acts of Commodore Moore, virtually revokes the Proclamation of President Houston relative to the Navy.”

Second Sortie: The Battle of Campeche, 1843

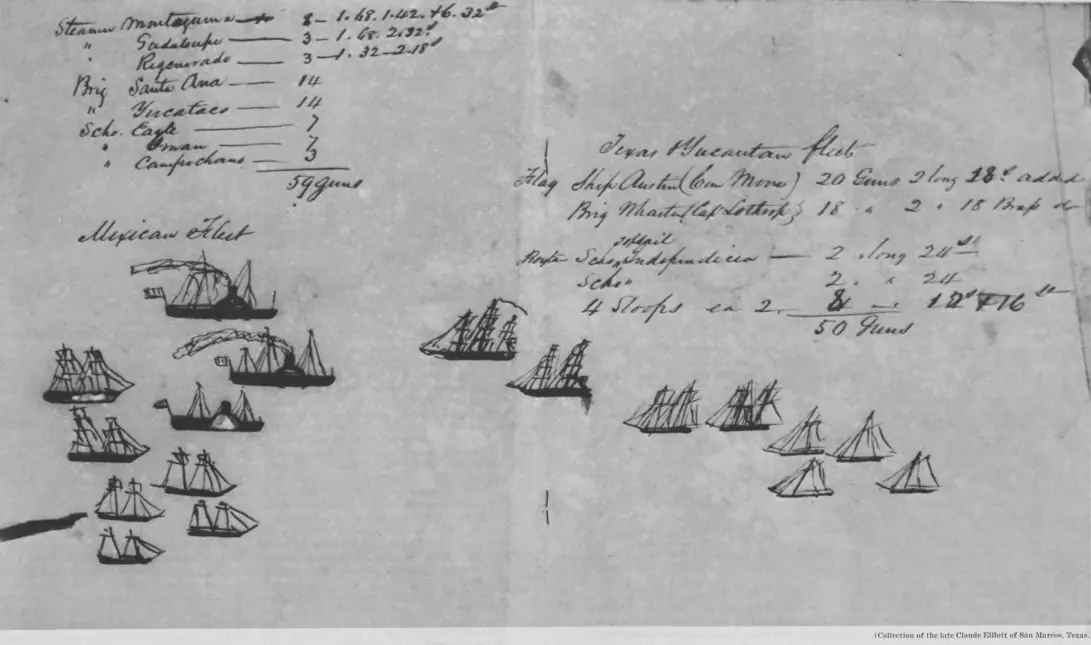

Moore’s ships arrived off the coast of Mexico on April 27, 1843 and joined up with several schooners and five gunboats of the Republic of Yucatán Navy, commanded by former Texas Navy Captain James D. Boylan.

Beginning on April 30, and continuing until May 16, the allied Texan-Yucatán fleet fought a series of engagements against Mexico’s Navy in the waters near Campeche.

These clashes were inconclusive, resulting in damage to both sides but no ships lost. However, the Mexican fleet suffered more casualties—about 30 killed and 50 wounded, compared to 7 killed and 24 wounded on the Texan side.

The Mexican fleet retired for repairs, resulting in the lifting the blockade of Yucatán

The Battle of Campeche remains the only recorded instance in naval history where sailing vessels defeated steam warships in combat. European observers took note, debating whether steam had truly revolutionized warfare. For Texans, it was a point of pride — proof that the Navy could humble Mexico’s modern fleet.

The fight also entered American legend. As a marketing stunt, the famous gunsmith Samuel Colt engraved the battle scene on the cylinders of his 1851 and 1861 Colt Navy revolvers. Thus, the clash off Campeche Bay was memorialized not only in naval annals but also in the iconography of the American frontier.

Court Martial of Captain Moore

After the battle, Moore returned to Galveston after first stopping in Yucatán for payment, and in New Orleans to return members of his crew.

Moore returned to Galveston in July 1843, where the populace celebrated him as a hero. However, he was dishonorably discharged from the Navy and tried by court martial on six charges of embezzlement of public funds, contempt, disobedience to orders, treason, and murder (for the execution of mutineers about the San Antonio in 1842).

After a long trial of 72 days, the court, which consisted of army officers, found Moore not guilty on all charges except four minor charges of disobedience. Houston, angry with this result, issued a “veto” of the court’s findings, writing, “The President disapprove of the proceedings of the court in toto, as he is assured by undoubted evidence, of the guilt of the accused in the case of E.W. Moore, late Commander in the Navy.”

Moore published a pamphlet, To the People of Texas (1843), in which he defended his actions and accused Houston of undermining the Republic’s honor. In 1844, he was restored to his command, though the Navy itself was already in steep decline, as Houston continued his policy of defunding the navy and auctioning off its assets.

The feud epitomized the division of Texas politics: Houston’s vision of austerity and diplomacy versus Lamar’s dream of naval activism and alliances. Campeche proved the Navy’s potential; Houston’s policies ensured its demise.

Legacy of the Yucatán Alliance

Though belittled by Sam Houston, the Texas Navy played a key role in winning intentional recognition for Texas and helping the Yucatanians secure autonomy within Mexico. The Battle of Campeche forced Mexico to suspend its blockade of the Yucatán peninsula and complicated land operations against the separatist region.

Importantly too, the threat of Texan naval dominance in the Gulf raised fears of a prolonged blockade of Mexico’s ports of trade, which would have crippled the economy.

As a result, Mexico moved to make peace with the Republic of Texas. In June 1843, Mexico and Texas agreed to an armistice, ending hostilities between the two nations. This agreement was a significant diplomatic development, negotiated through British mediation and occurring in part because of the Texan-Yucatanian naval victory at the Battle of Campeche.

Though not a formal peace agreement, the armistice represented de facto Mexican acceptance of Texas independence, for the first time since the Texas Revolution.

For its part, Yucatán briefly negotiated a return to Mexico, retaining autonomy under the 1824 constitution. The alliance with Texas faded. The Navy, starved of funds and left with only a handful of aging ships, disintegrated. With Texas annexed to the United States in 1846, the end came formally. On February 19, 1846, the ships of the Republic of Texas Navy were transferred to the U.S. Navy, declared unfit, and discarded.

Officers who sought commissions in the American service were denied. Many, like Moore, spent years petitioning for recognition and back pay. In 1857 Congress awarded him five years’ pay, and Moore County in the Texas Panhandle was later named in his honor.

📚 Curated Texas History Books

Dive deeper into this topic with these handpicked titles:

- Wars of the Mexican Gulf: The Breakaway Republics of Texas and Yucatan, US-Mexican War, and Limits of Empire 1835-1850

- William Walker’s Wars: How One Man’s Private American Army Tried to Conquer Mexico, Nicaragua, and Honduras

- The Raven: A Biography of Sam Houston

Texapedia earns a commission from qualifying purchases. Earnings are used to support the ongoing work of maintaining and growing this encyclopedia.