In the spring of 1993, a remote compound outside Waco, Texas, became the site of one of the most consequential law enforcement operations in modern American history. What began as an attempt to execute a weapons-related search warrant escalated into a 51-day standoff between the U.S. government and a religious sect known as the Branch Davidians.

While the siege itself was unprecedented in scale and intensity, its legacy proved even more far-reaching. It damaged public trust in federal law enforcement, framed debates over religious liberty and state sovereignty, inspired a major act of domestic terrorism, and sparked new controversy around child protective services.

What happened outside Waco in 1993 would not remain an isolated event—it became a national symbol, used by critics, politicians, and extremists alike to reshape how Americans understood the power and limits of government.

The Standoff at Mount Carmel

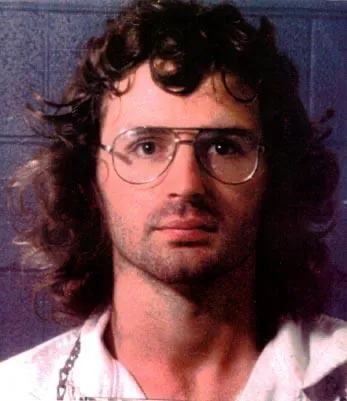

The Branch Davidians were an offshoot of the Seventh-day Adventist tradition, led at the time by David Koresh, a self-proclaimed prophet who claimed apocalyptic authority over his followers. The group had settled at Mount Carmel, a property in eastern McLennan County, where they stockpiled weapons and attracted national attention for their unorthodox theology and reports of child abuse and polygamy.

On February 28, 1993, the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms (ATF) attempted to serve a warrant for alleged firearms violations. An exchange of gunfire erupted under disputed circumstances, levaing four federal agents and six Davidians dead. In the wake of the failed raid, the FBI took over and initiated a 51-day siege involving armored vehicles, tear gas, loudspeakers, and psychological tactics. Negotiations led to some releases, particularly of children, but most members remained inside.

The standoff ended on April 19, 1993, when the FBI launched a final assault using gas in an effort to force a surrender. A fire broke out inside the compound and quickly consumed the building. Seventy-six people died, including Koresh and at least 20 children.

In two subsequent reports, federal investigators concluded that the Davidians started the fire, though this was disputed by Branch Davidian survivors and their attorneys, as well as anti-government activists and conspiracy theorists.

Public Response in Texas and the Nation

The immediate reaction in Texas was a mixture of horror, confusion, and mounting distrust. Waco residents had lived for weeks under the cloud of national scrutiny and military-style occupation. In more rural or libertarian parts of the state, the use of overwhelming federal force against a Texas-based religious group—however fringe—struck a nerve. Even among those who viewed the Davidians with skepticism, the scale of the response seemed disproportionate.

Nationally, the event became a defining moment for public perceptions of federal power. Many Americans blamed Koresh for leading his followers to ruin. But a substantial share of public criticism focused on federal agencies, particularly the FBI and ATF, for escalating a volatile situation. Televised footage of tanks and armed agents contributed to a growing narrative of government overreach—a sentiment that would intensify in the coming years.

The siege occurred just weeks into the new Clinton administration, placing unexpected pressure on a government still assembling its leadership. That pressure soon focused on one official in particular: the new Attorney General, Janet Reno.

Political Fallout and the Clinton Administration

Janet Reno, confirmed just days before the siege began, ultimately approved the final FBI assault. After the fire, she appeared before the press to take responsibility for the outcome—a rare public admission that, while lauded by some, did little to calm the storm. The Clinton administration was forced to navigate a complex political landscape: defending its law enforcement agencies while acknowledging widespread unease with the result.

Internally, the siege prompted a series of federal reviews, including a Justice Department report and congressional hearings. While these investigations found no deliberate misconduct, they cited flawed intelligence, poor communication, and insufficient planning. The event significantly shaped how future federal operations were handled, particularly in cases involving religious or separatist groups. Reno would later order reforms in FBI crisis management and use-of-force protocols, and the government became more cautious in similar standoff situations going forward.

The siege also had implications for President Clinton’s broader relationship with rural and conservative voters. Though the incident was not directly his fault, it became part of a growing narrative among critics that his administration embodied liberal elitism and intrusive government—a perception that hardened during later debates over gun control, federal mandates, and religious freedom.

A Catalyst for Extremism

Perhaps the most consequential and dangerous legacy of the Waco siege was the inspiration it provided to extremist groups. In the years following 1993, Waco became a rallying cry for militias, white supremacist organizations, and anti-government radicals who viewed the incident as proof that the federal government would crush dissent by force.

One of the most infamous responses came from Timothy McVeigh, who cited the Waco siege—and its timing—as motivation for his bombing of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City on April 19, 1995, exactly two years after the Mount Carmel fire. The attack killed 168 people and remains the deadliest act of domestic terrorism in U.S. history.

In Texas, Waco also helped fuel a broader culture of anti-federal sentiment. Conspiracy theorist Alex Jones, then an emerging radio personality in Austin, repeatedly pointed to the siege as evidence of government tyranny. He incorporated Waco into his early media narratives, helping to define what would become a long-running strand of Texas-based political paranoia. Jones was far from alone: Waco became part of the lore for sovereign citizens, militia recruiters, and gun rights activists across the country.

The siege’s imagery—burning buildings, armored vehicles, and dead children—proved powerful propaganda for those seeking to delegitimize federal institutions. In time, Waco joined Ruby Ridge, another federal standoff from 1992, as a central grievance in the far-right worldview.

Child Welfare Policies

A less visible but equally important legacy of the siege involved child protection policy. One of the original justifications for the ATF and FBI’s aggressive posture was the allegation of child sexual abuse inside the compound. However, the agencies pursuing the case were not child welfare specialists, and state-level actors like Texas Child Protective Services (now under DFPS) were largely sidelined once the siege began.

Some child advocates questioned whether the right agencies were even in charge. CPS had previously investigated the Davidians but failed to build a strong enough case to act decisively. Once the siege began, law enforcement—not social services—controlled the situation, and efforts to protect children became subordinate to tactical and security concerns.

In retrospect, critics argued that the children might have been better served by earlier, quieter intervention or by a more coordinated inter-agency response that centered their welfare. Others contended that the use of aggressive tactics—tear gas, psychological warfare, and siege conditions—put children at greater risk than any abuse they may have suffered under Koresh.

Though no specific reforms to DFPS were publicly tied to the siege, the incident contributed to broader debates about how federal and state agencies handle complex, high-risk child welfare situations. It also raised enduring questions about whether law enforcement goals and child protection goals can be reconciled in moments of crisis.

A Turning Point in American Policing and Protest

The Waco siege has continued to cast a long shadow over the politics of policing, protest, and federal power. In Texas, it became a symbolic moment—a cautionary tale of what happens when outside forces descend on local communities with overwhelming force and insufficient understanding. For many conservatives and libertarians, it validated fears of a distant, unaccountable federal state. For others, it revealed how law enforcement can fail to balance public safety with constitutional rights.

The incident also left its mark on federal training and engagement policies. Negotiation tactics were revamped, armored vehicle usage became more tightly regulated, and inter-agency command structures were clarified. But the damage to public trust had already been done. For a generation of Americans—especially in Texas—the images of tanks and smoke outside Waco would come to symbolize more than a failed raid. They represented the moment when political and spiritual fringe collided with the full weight of modern government, and neither side walked away unchanged.